| After another huge selloff, it's best to say that what's going on isn't an eruption or an earthquake. If there's a good geological metaphor, it might just be a landslide; it doesn't start so dramatically or damagingly, but as time goes by gains momentum and gets harder to stop. That makes this selloff different from most, and also makes it even harder to grasp where the market is going next. Bear in mind that Europe was closed Monday, which meant lower liquidity, so comparisons of world markets are slightly distorted. That said, at one point the S&P 500 had given up all its gains relative to the rest of the world since the beginning of last year. It ended very close to that level, although the odds are that Europe will sell at Tuesday's opening, making the S&P's relative performance a little better: The dollar continues its fall, and this amounts to much more pain for the rest of the world. It's foreigners who have poured money into US stocks in the last few years, and the combined decline of US stocks and the currency means hideous losses. In two months, the S&P is down more than 25% in Swedish krona, but only 16% in dollars: Why might this be the beginning of a landslide, or a steady move of the continental plates? The rest of the world is hugely exposed to the US, treating its stock market as a piggy bank during the time of the "US exceptionalism" trade. This exposure has long looked dangerous, but when the American economy whirred like a perpetual motion machine, and provided the safest jurisdiction on the planet, that risk looked minimal. Once confidence is lost and people try to repatriate money, the landslide can build momentum. It needed a catalyst, a first rock to slip, and Trump 2.0 seems to have provided it. The latest rock slipped in an early morning social media post by President Donald Trump. Here is his latest wisdom on interest rates: For context: - None of the "many" calling for preemptive cuts have mentioned it to me.

- Inflation is falling nicely. But prices of services, (presumably not "things"), are still rising uncomfortably. It's far too soon to say that there is virtually no inflation.

- The European Central Bank has made seven 25-basis-point cuts, as opposed to four by the Fed, in large part because its economy is much weaker and inflation lower.

- Many people who didn't want Kamala Harris to be president were enthusiastic supporters of the September rate cut. There was a growth scare at the time.

- Perhaps most importantly, this post includes no threat to fire Powell. So maybe the White House strategy is to bully him into submission rather than get rid of him.

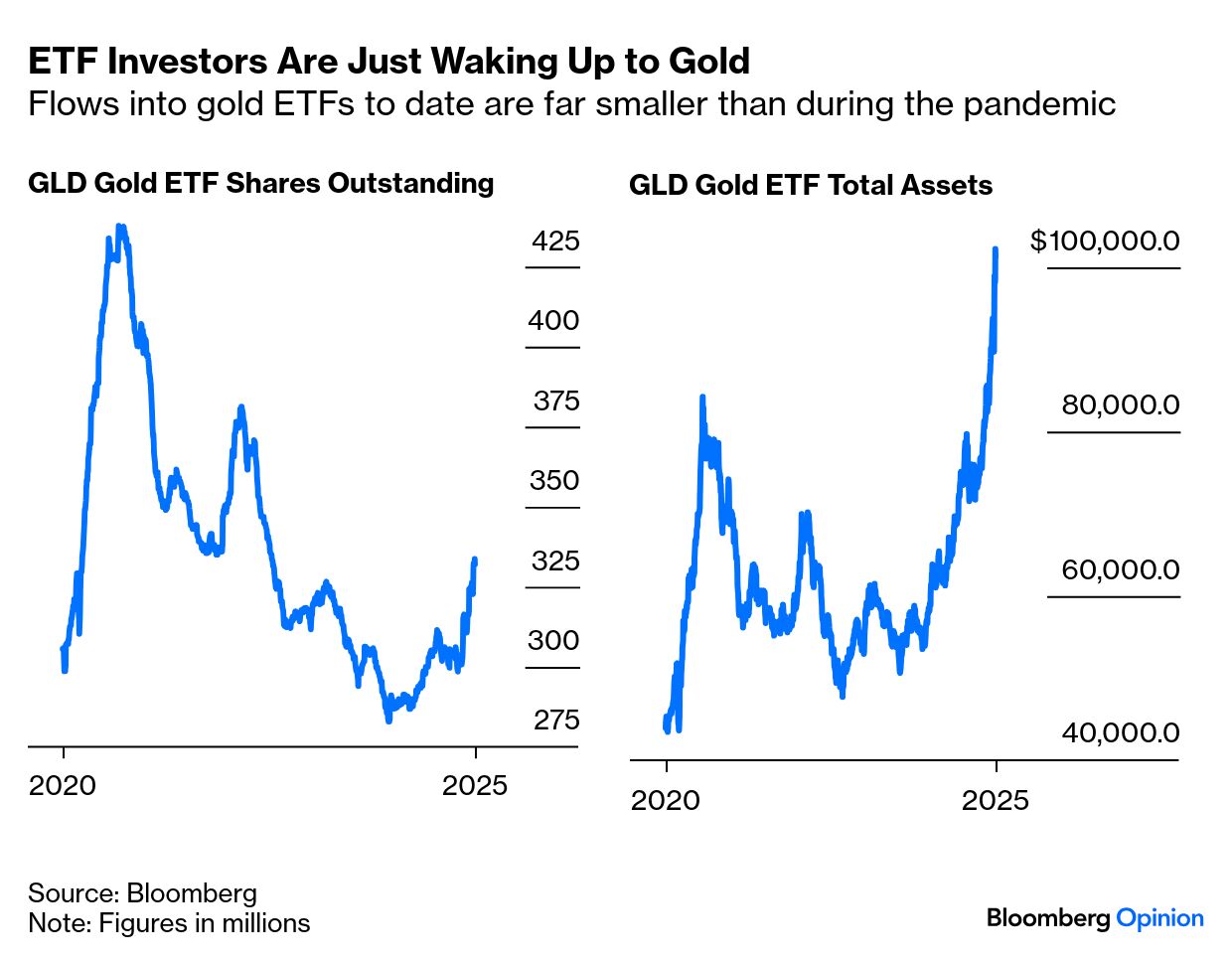

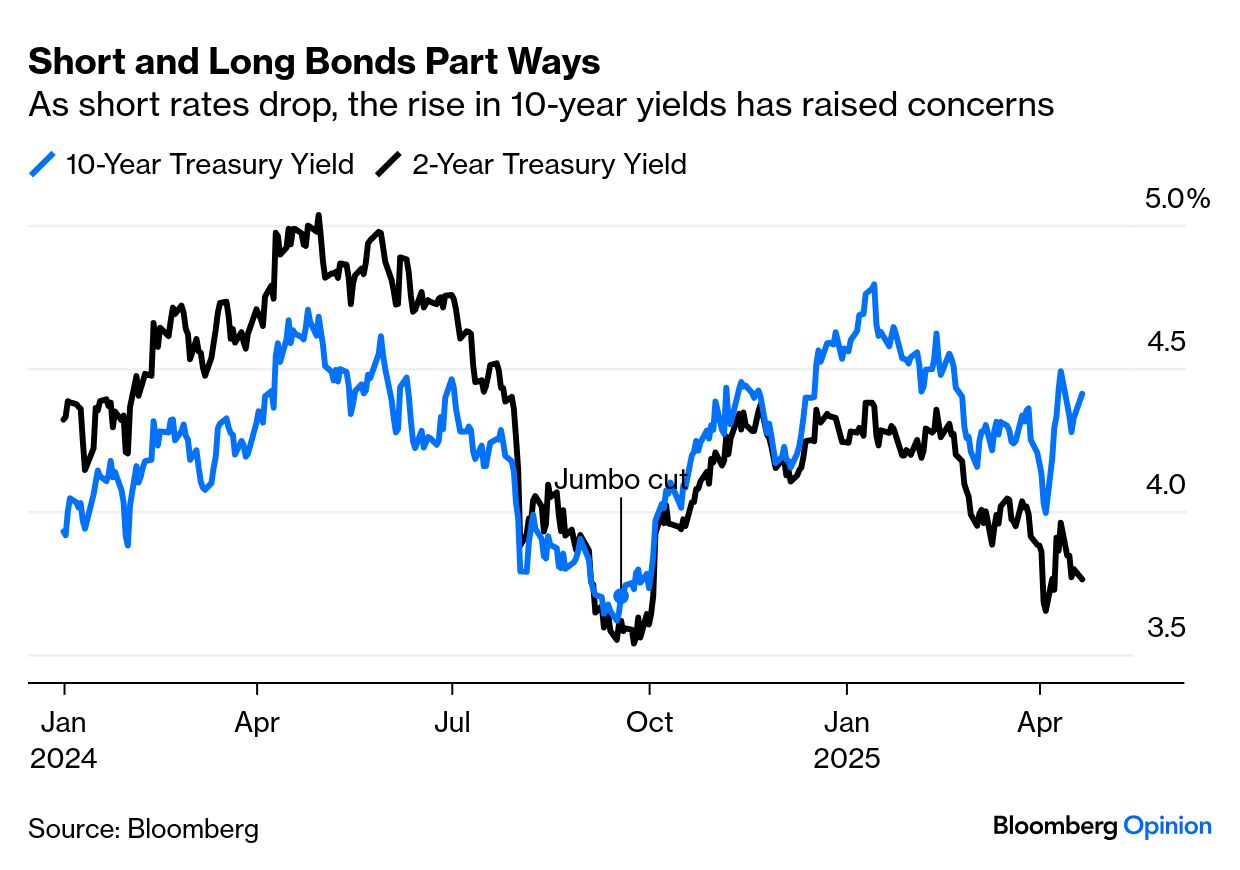

The problem, as many traders war-gamed out as they read the post, is that the president's position perversely makes it harder for the Fed to cut unless the case to do so is overwhelming. Otherwise, it will lose even more credibility and appear to buckle to political pressure, doing much more damage to confidence in the dollar. America's polarized politics make this even more difficult. The gap between Republicans and Democrats over expected inflation for the next year is at a new extreme: The fact that so many are convinced that inflation is coming right back is dangerous, as it can be self-fulfilling. And the confidence of Republicans means that the president faces a danger of losing his base if prices unmistakably rise again. All of this feeds into the attack on the dollar. It has lost ground against a range of developed market currencies, and particularly against gold — but not against the Chinese yuan, still heavily managed by authorities there: The White House has complained that the strong dollar is a "non-tariff barrier" to trade. That's a stretch, but it has certainly made US exports less competitive, and that problem is now being remedied. The problem is China. This is how the real broad effective exchange rates (against all trading partners and accounting for differences in inflation) of the two economic superpowers have moved following the shock Chinese devaluation of August 2015. The yuan has grown much more competitive since the Fed started raising rates in 2022: If the main US aim is to reduce its trade deficit with China, then the conflict is not going well. Meanwhile, the surge in gold demands to be taken seriously. In real terms, accounting for inflation, it has broken out in the last few months, at last far exceeding the peak set during the horrors of stagflation and the Iran hostage crisis in 1980. This is the real gold price since Richard Nixon ended the Bretton Woods gold peg to the dollar in August 1971: Denominating stocks in gold, rather than dollars, to help capture the balance of greed and fear represented by the two asset classes, shows that the S&P 500 is now back to its Covid-era lows: The dynamics of the demand for gold could push this a lot further. The total assets of the largest gold bullion exchange-traded fund, run by State Street Global Advisors, are at a record, but that's largely because of the gold price. The total number of shares outstanding, a good gauge of retail interest, is still far below the Covid-shelter peak of 2020. That implies that as US investors — relatively shielded so far by the fall of the dollar — start to get nervous, they have plenty of space to buy a lot more gold:  Driving the greatest concern, as ever, is the bond market. Short-term bond yields are falling, as would be expected when the economy is at risk of slowing and people need a shelter. What is startling, and completely contrary to the experience of decades, is the rise in longer yields. It isn't normal for money to flow out of the world's safest investment when people are worried. While 10-year yields are still not at any kind of exceptional level, the direction of change is unsettling. Maybe a Fed rate cut would help, but experience since the 50-basis-point cut last September shows that it might well not:  Does the landslide keep gathering momentum from here? Not necessarily — US exceptionalism was so strong in the first place because stock earnings kept growing. We're about to hear from a lot of companies about their bottom line, and that might easily shift perceptions. There's also the chance of a few big trade deals, most obviously with Japan, that could ease nerves on the markets and suggest that the US won't push too hard on tariffs. But against that, talks to date have yielded nothing tangible, and as many of the biggest economies don't have large trade barriers in the first place, it's difficult for them to offer much. For investors, there's also the reassurance that the US has looked overdone and the rest of the world has appeared cheap for ages. There are ways to protect themselves from the falling US stock market — but unfortunately, they'll exacerbate the problem. |

No comments