Fed’s broken pledge

Fed Timing

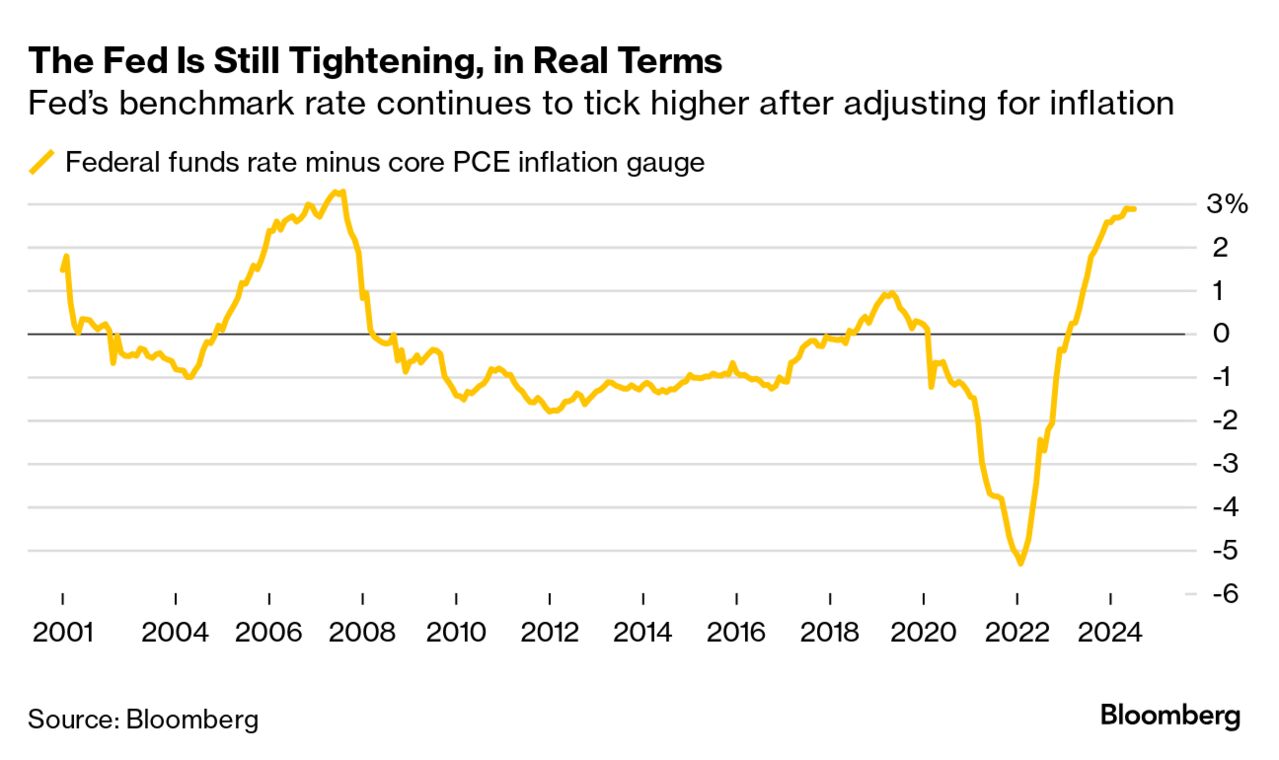

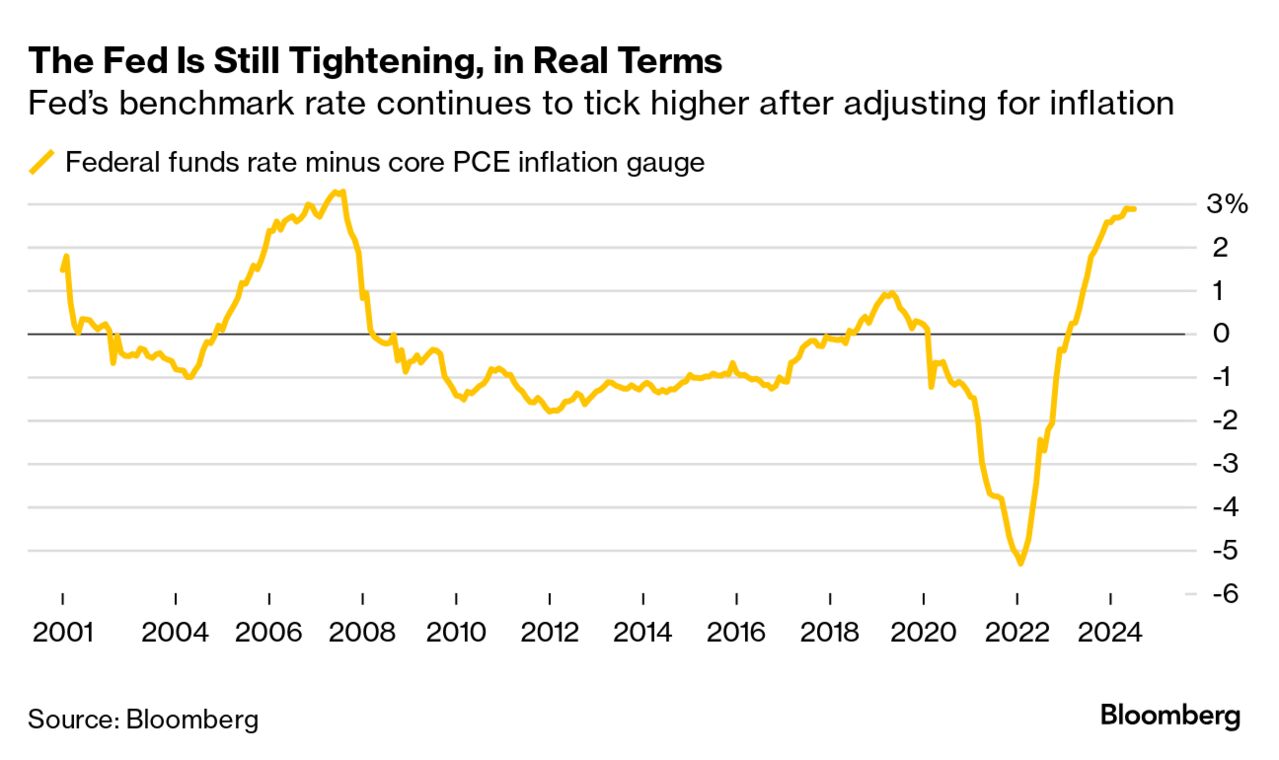

As US consumer price pressures eased markedly last year, economists pointed out how the Federal Reserve, even just by standing pat on interest rates, was effectively tightening its policy stance, because the benchmark rate was actually still going up after adjusting for inflation.

Especially considering the lags between policy actions and their impact on the economy, that argued for adjusting interest rates even before inflation got all the way back to the Fed's 2% target. Indeed, Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues never predicated lowering rates on getting to 2%.

The latest data showed that, as of June, the Fed had got most of the way there. The Fed's preferred inflation gauge, the PCE price index, was up 2.5%, and the core measure, which strips out food and energy, rose 2.6%. That compares with their respective peaks of 7.1% and 5.6%.

"It would be too late" to wait until achieving 2% to cut rates, Powell said last December. "You'd want to be reducing restriction on the economy well before 2%" in order not to "overshoot," he said.

Yet last week, the Fed still stood pat. And with Friday's employment report coming in weaker than almost everyone anticipated for July, the worry now is that policymakers might have left things a little late.

"The Fed backed away from their promise of adjusting the funds rate downward to keep the real rate from getting too tight as the economy cooled," Steven Blitz, chief US economist at Lombard Street Research, wrote in a note Friday.

Fed officials swiftly began to play down the weak jobs report, highlighting that it was just one figure. Thomas Barkin, the Richmond Fed president, said at the end of last week he wouldn't take back his vote to keep rates steady on Wednesday. Powell on Wednesday also highlighted that the economy remains in solid shape.

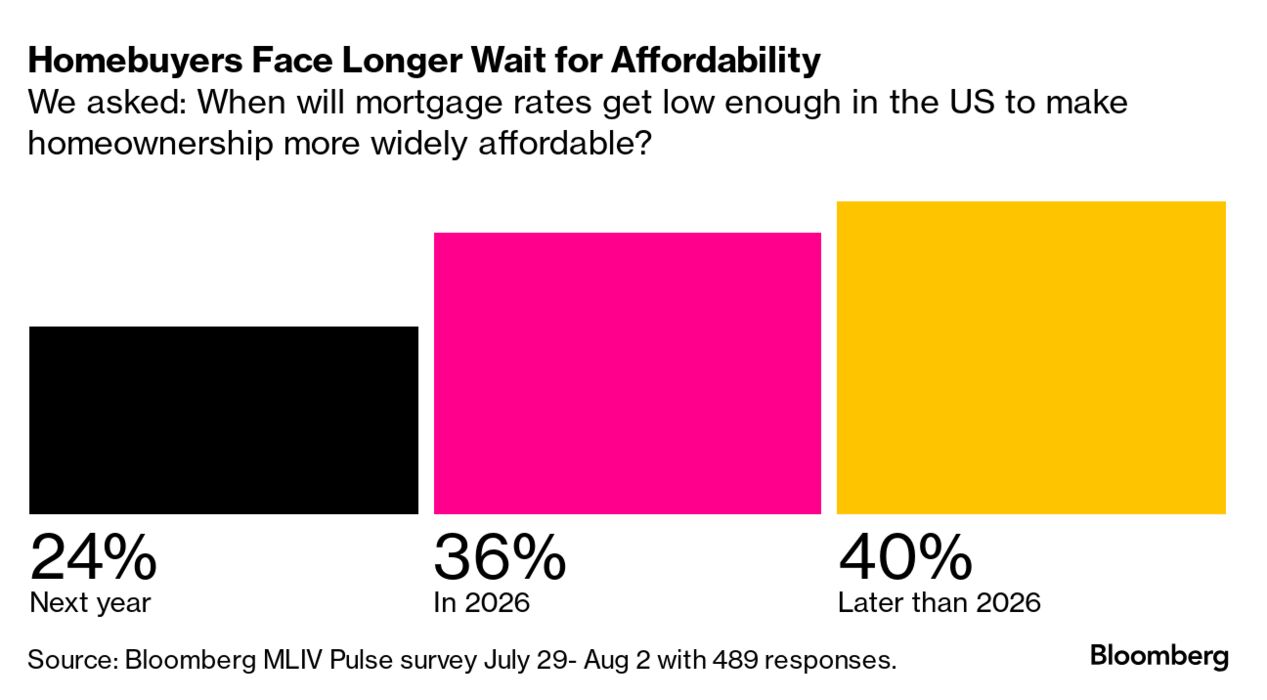

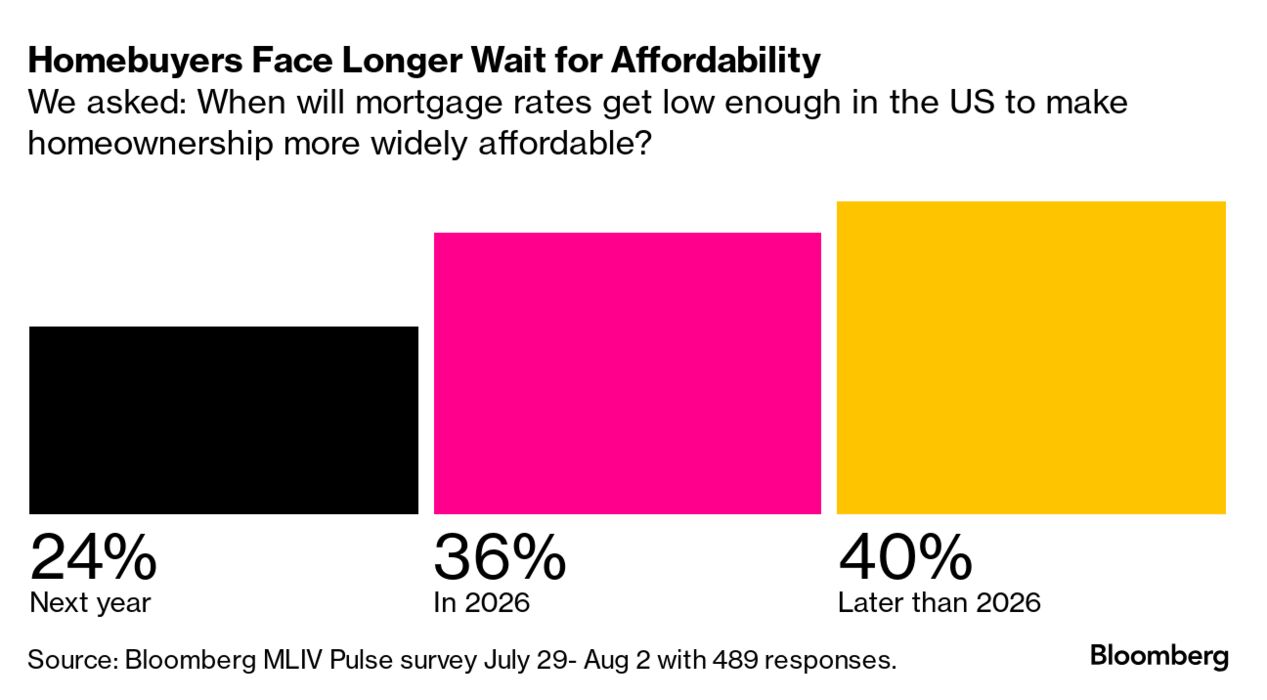

But, as was the case when the Fed started hiking rates in March 2022, it will take time for cuts to have an impact. Mortgage rates won't come down in lockstep — as already seen in recent weeks, with 30-year fixed rates staying not far from 7% despite a big rally in the Treasuries market that's taken benchmark 10-year yields under 4%.

Even with Wall Street expecting a Fed easing cycle, just 24% of 489 poll participants in the latest Bloomberg Markets Live Pulse survey see mortgage rates falling low enough to make homeownership more widely affordable in 2025.

Compared with some past policy-easing cycles, the Fed has some advantages this time, Blitz highlighted. Households and businesses aren't leveraged up. And the starting point for the Fed's benchmark, at its current (nominal) target range of 5.25% to 5.5% leaves officials a whole lot of space for easing.

But given how high real rates now are, and the signs of a turn in the economy, Fed watchers increasingly see Powell and his colleagues as behind the curve. That prompted a wave of forecast changes, including from JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, to incorporate faster, and possibly bigger, rate cuts ahead.

As US consumer price pressures eased markedly last year, economists pointed out how the Federal Reserve, even just by standing pat on interest rates, was effectively tightening its policy stance, because the benchmark rate was actually still going up after adjusting for inflation.

Especially considering the lags between policy actions and their impact on the economy, that argued for adjusting interest rates even before inflation got all the way back to the Fed's 2% target. Indeed, Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues never predicated lowering rates on getting to 2%.

The latest data showed that, as of June, the Fed had got most of the way there. The Fed's preferred inflation gauge, the PCE price index, was up 2.5%, and the core measure, which strips out food and energy, rose 2.6%. That compares with their respective peaks of 7.1% and 5.6%.

"It would be too late" to wait until achieving 2% to cut rates, Powell said last December. "You'd want to be reducing restriction on the economy well before 2%" in order not to "overshoot," he said.

Yet last week, the Fed still stood pat. And with Friday's employment report coming in weaker than almost everyone anticipated for July, the worry now is that policymakers might have left things a little late.

"The Fed backed away from their promise of adjusting the funds rate downward to keep the real rate from getting too tight as the economy cooled," Steven Blitz, chief US economist at Lombard Street Research, wrote in a note Friday.

Fed officials swiftly began to play down the weak jobs report, highlighting that it was just one figure. Thomas Barkin, the Richmond Fed president, said at the end of last week he wouldn't take back his vote to keep rates steady on Wednesday. Powell on Wednesday also highlighted that the economy remains in solid shape.

But, as was the case when the Fed started hiking rates in March 2022, it will take time for cuts to have an impact. Mortgage rates won't come down in lockstep — as already seen in recent weeks, with 30-year fixed rates staying not far from 7% despite a big rally in the Treasuries market that's taken benchmark 10-year yields under 4%.

Even with Wall Street expecting a Fed easing cycle, just 24% of 489 poll participants in the latest Bloomberg Markets Live Pulse survey see mortgage rates falling low enough to make homeownership more widely affordable in 2025.

Compared with some past policy-easing cycles, the Fed has some advantages this time, Blitz highlighted. Households and businesses aren't leveraged up. And the starting point for the Fed's benchmark, at its current (nominal) target range of 5.25% to 5.5% leaves officials a whole lot of space for easing.

But given how high real rates now are, and the signs of a turn in the economy, Fed watchers increasingly see Powell and his colleagues as behind the curve. That prompted a wave of forecast changes, including from JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, to incorporate faster, and possibly bigger, rate cuts ahead.

No comments