| We are about to discover whether Reed Smoot and Willis Hawley were right all along. Donald Trump said he was a protectionist, and he has delivered effective levies to match the infamous tariffs named for the Depression-era US legislators. That's illustrated by Capital Economics: That is also the shape of the new Trump trade policy, which now looks likely to stay in place at least for a matter of months, and possibly much longer. If we are indeed at the new trade normal, conventional wisdom has been proved wrong on at least three important points: - Tariffs are far higher than expected in January (or after the April 8 delay).

- They have had very little effect on inflation or unemployment to date.

- Virtually nobody has retaliated.

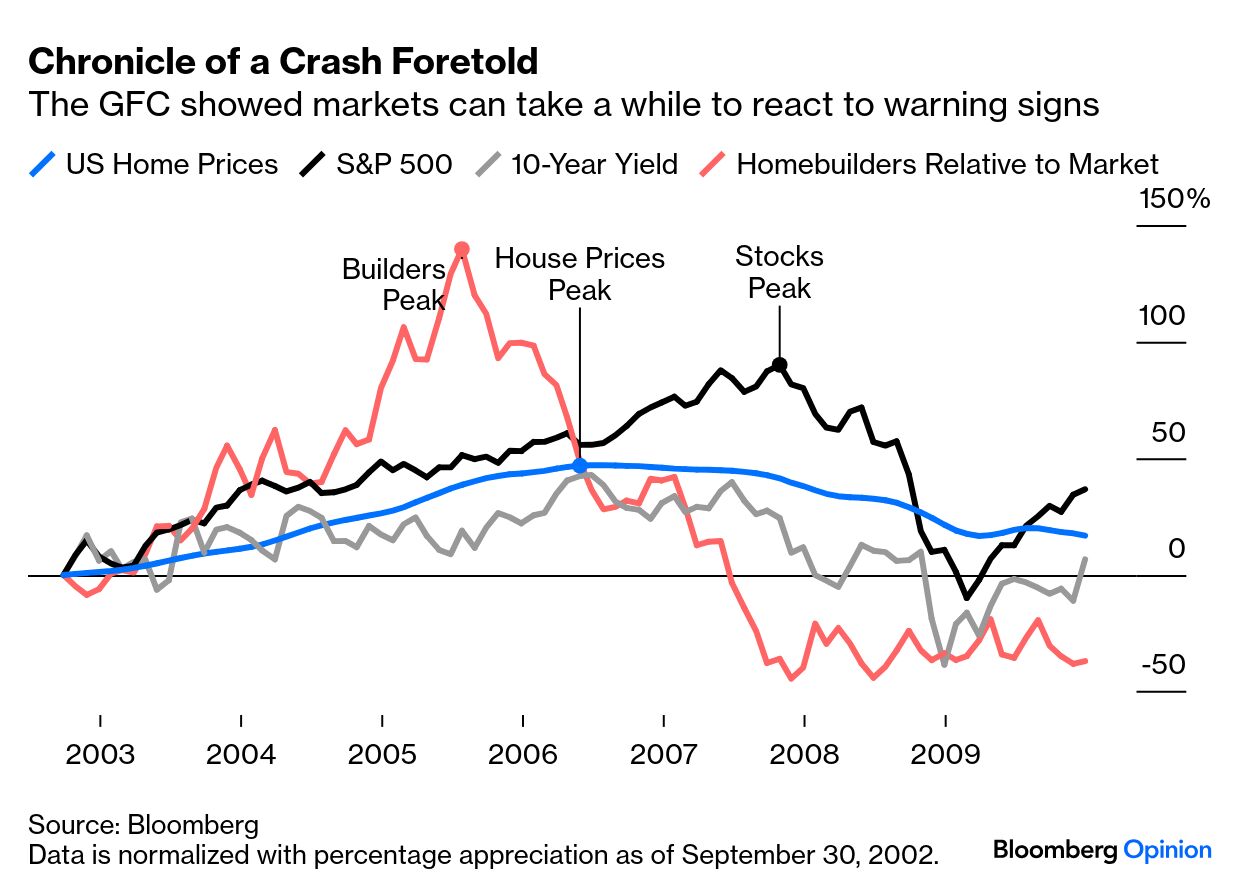

The latter two have counteracted any damage that might have been done for the first. Judged by his ability to get what he wants, the story so far is of a crushing success for Trump. Others are not fighting back. Neither the markets nor the macroeconomic data to date place any limit on his freedom of action — the US stock market, fortified by Monday's bounce, remains very close to its all-time high. Tariffs are also producing helpful revenue for the government. In all, things are going far better than they did for Smoot and Hawley, who passed their levies in 1930 and were both ejected from Congress in 1932. That protectionist episode came when the US had a trade surplus, and was bedeviled by widespread retaliation as the Depression deepened. This time, the conditions are better. This is a policy in which Trump deeply believes, and it has taken no little political skill to enact it. Now we need to find out if it works. Economic logic is remorseless, but it's not like physics; it operates through the decisions of millions of people and can take years to play out. Markets follow the economy in the long term, but in the shorter term they can get things wildly wrong. Exhibit A is the Global Financial Crisis, caused largely by great overinvestment in US housing. The bubble in homebuilders' stocks peaked in 2005, and in house prices a year later. The stock market surged on for another year, and the crash wasn't until 2008:  This time around, the new system should be inflationary for the US, which effectively has a new consumption tax, and deflationary for everyone else, as their industries have just been rendered less competitive. And it should slow economic activity for everyone. If it does bring back manufacturing, that will take time and reduce tariff revenues. That isn't to say that the shock will be anything like as bad as the disaster of 2008 — but the experience to date, with companies bringing imports forward to avoid tariffs, doesn't prove that protectionism will work out better than it did for Smoot and Hawley. Jonathan Pingle, chief US economist at UBS, estimates the effective tariff rate has just risen from 16% to 19%, roughly where it was under Smoot-Hawley, and cautions that uncertainty hasn't disappeared. Most significant is the threat of sectoral tariffs on pharmaceuticals. The president has suggested a 200% levy. In the unlikely event that this came to fruition, it would on its own raise the overall US effective tariff rate by another 13 percentage points. As it stands, the latest increment should slow US economic growth by a further 0.2 percentage points; the tariff hikes to date had already brought the UBS estimate down to 1.6% from 2.5%. So, how to explain a market rally after this? Lower growth expectations bolster the case for rate cuts, while US company profits are rising, likely to benefit from a cheaper dollar and unhindered by retaliatory tariffs. All of that suggests that US equities can endure in a Smoot-Hawley world — at least until the logic has played out in full.  | | | To appreciate the absurdity of what is happening, look only to Switzerland, due to suffer a 39% tariff — the highest on any developed nation — as punishment for its big trade surplus with the US. First, note that the surplus is relatively new, and entirely driven by a sudden boom in Swiss exports (largely gold bullion to the US earlier this year). It has nothing to do with any great limitation on US exports to Switzerland, and the Swiss have little to offer because tariffs are already minimal: Further, the Swiss franc's safe-haven status makes it one of the world's most highly valued currencies. The dollar has depreciated by 20% over the last decade, making imports from the US far more competitive. The US has widely complained about non-tariff barriers, and particularly about artificially weak currencies. There is no way this charge can stick to the Swiss: Switzerland is now scurrying to find something to offer. It's hard to imagine what this will be, and even harder to envision how anyone will benefit. |

No comments