| The stock market is always narrow. One of the most influential articles in academic finance of recent years, Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills? by Arizona State University's Hendrik Bessembinder, found that over 90 years: Just 86 stocks have accounted for $16 trillion in wealth creation, half of the stock market total... All of the wealth creation can be attributed to the thousand top-performing stocks, while the remaining 96% of stocks collectively matched one-month T-bills.

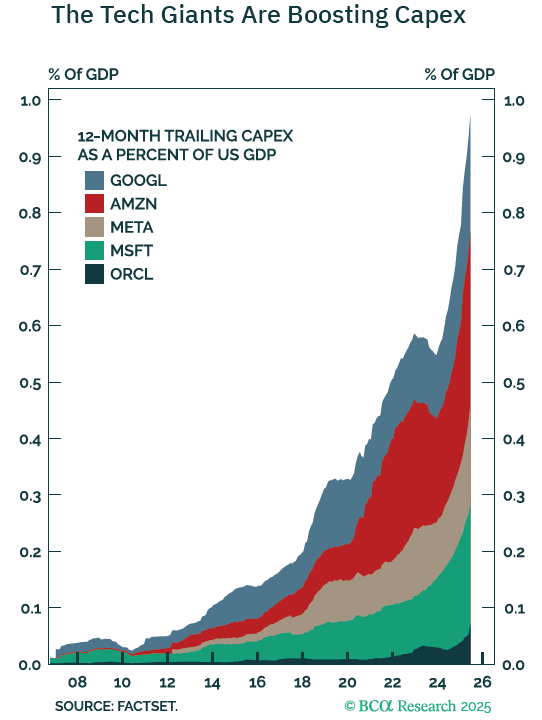

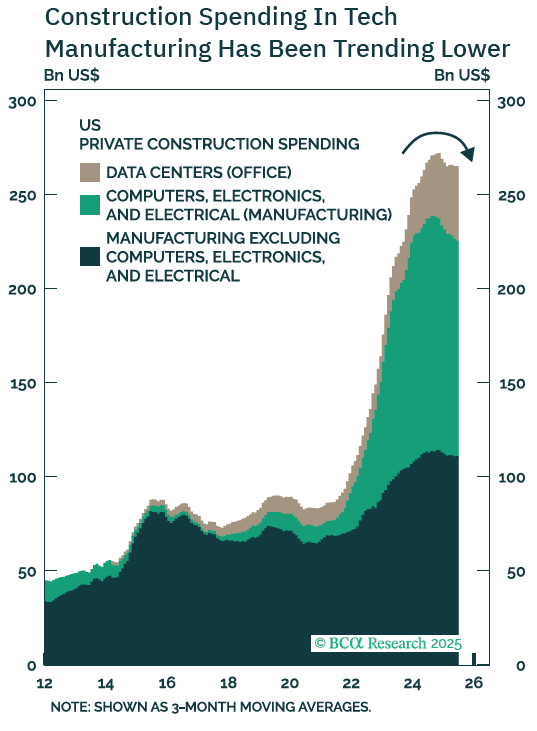

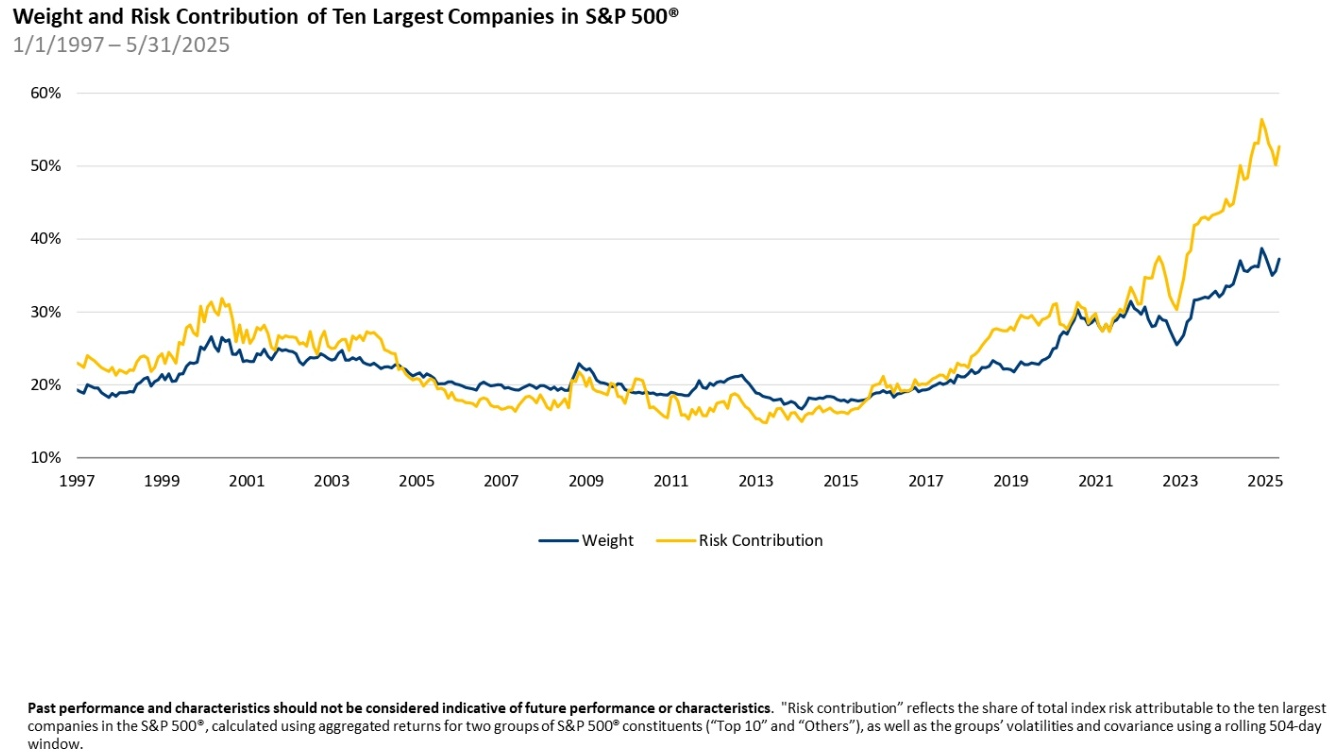

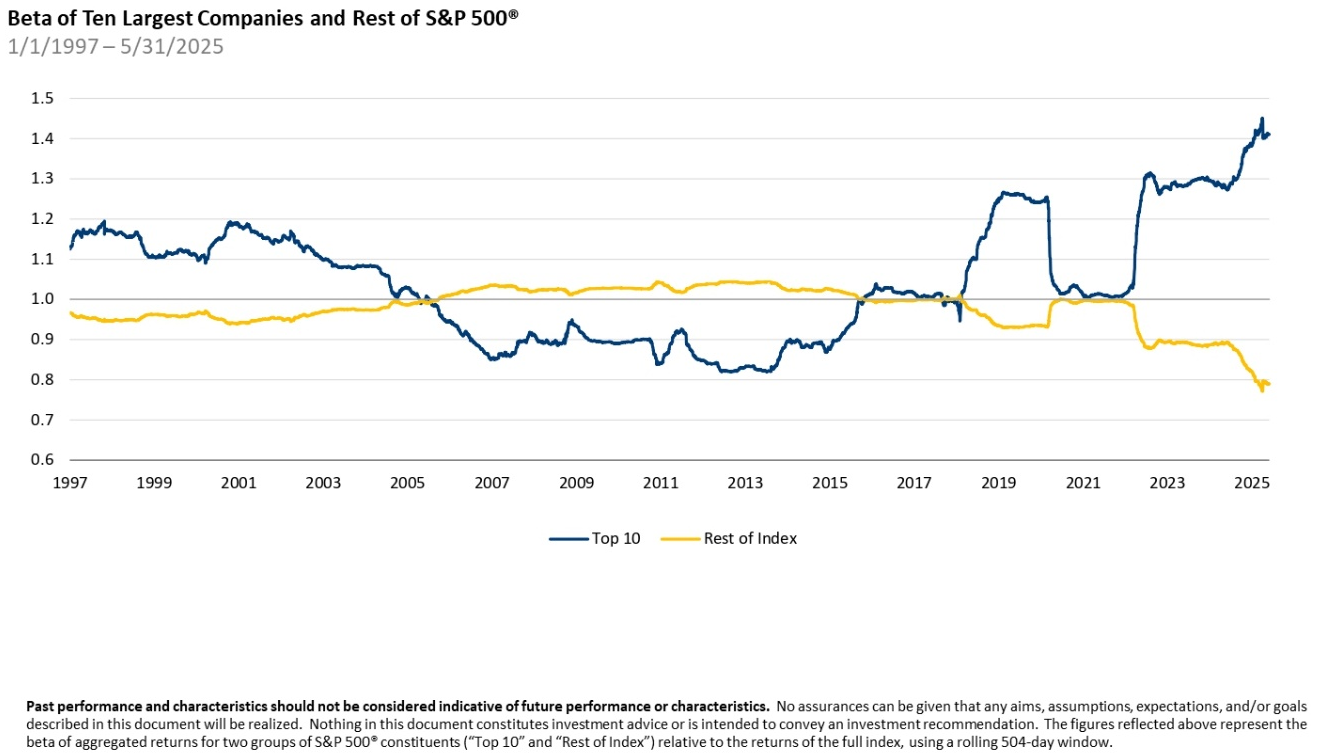

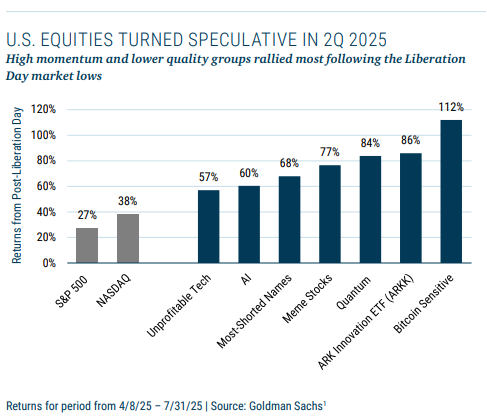

A follow-up study covering the three decades from 1990 to 2020 found that more than half of 64,000 public stocks lagged one-month Treasury bills. Capitalism was ever thus. Over time, a few big players mop up big time, while others just match the returns on a bank account. This isn't necessarily bad for the economy, as at any one time there will always be a few companies going gangbusters. And it's not so bad for investors: Provided they're well diversified, they'll hold a few of the big winners, and enjoy returns much better than Treasury bills. Still, it creates a dilemma. Investors can either 1) redouble efforts to spot the winners, go all in on them, and hope to do way better than the S&P 500; or 2) recoil at the risk that concentration could mean missing the winners, and put money in a capitalization-weighted index fund. History suggests that the return you make, even including the duds, will be good. Sadly for the active management industry, most chose the second approach. This matters, because the always narrow US stock market is much narrower than usual, and that makes life hard for anyone managing money. It's difficult to vary from the index without avoiding the Magnificent Seven tech platforms that benefit most from the artificial intelligence boom. A good day for Apple Inc., which has announced plans to bring production home to the US in a move that should help it avoid the new 100% tariff on chip imports, brought Bloomberg's Magnificent Seven index to a new all-time high. It has now exceeded its level from immediately before the DeepSeek shock in January, when AI stocks sold off in response to a new Chinese AI bot, and has also finally overtaken the rest of the market since that day: The rest of the world's stocks remain ahead of the Magnificents since the DeepSeek shock, largely thanks to the weak dollar: With outperformance for tech mega caps comes even greater market concentration. The equal-weighted S&P 500, a measure of the average stock's performance in which each constituent accounts for 0.2%, has set a fresh low compared to the overall index. This is led by a new low for value stocks — generally favored by stock pickers offering active funds — compared to growth. Companies with earnings growth are leading, and there aren't that many of them: Meanwhile, despite concerns that higher tariffs will dampen global economic activity, cyclical stocks are outstripping defensive names to an unprecedented extent. According to MSCI, they have topped a high set on the eve of the dot-com crash in 2000: There is an economic rationale for this. Tech groups' capital expenditures on AI are phenomenal. As BCA Research's Peter Berezin shows, five companies alone have made capex worth 1% of US gross domestic product:  Source: BCA Research But is it safe to bank on this undoubtedly massive buying spree? Most of it, Berezin says, is to buy AI chips from Nvidia. Investment in tech-related construction (for data centers and so on) has declined slightly in the last few months:  Source: BCA Research AI investment should feed into higher productivity for everyone, but that's not a given. For now, the benefits are intensely concentrated. For money managers, such narrow breadth makes it impossible to shine. They have to hold mega caps. But it's not clear why anyone should pay them for this service, while DE Shaw shows that the 10 biggest companies now account for more than half of the risk in the S&P 500 — risk for which investors aren't compensated:  Source: DE Shaw Further, the biggest mega caps are incredibly sensitive to the direction of the overall market (a concept known in the jargon as beta). Loading up on them also involves taking on much greater exposure to any generalized downturn:  Source: DE Shaw Even if narrowness is the norm, breadth this tight is not normal. By making life harder for managers, it arguably contributes to greater speculation. The best chance to beat such a narrow market is to load up on really risky assets — and the Boston-based fund manager GMO shows that this has happened since the post-Liberation Day tariff reprieve on April 9. The S&P 500 had rebounded 27% by the end of last month, but that was nothing compared to the performance of unprofitable tech groups, or heavily shorted companies, or plays on Bitcoin:  Source: GMO The dilemmas revealed by the Bessembinder research are at a new extreme. Mix that with a startlingly aggressive trade policy that will disrupt the companies currently winning, and the risks are clear. |

No comments