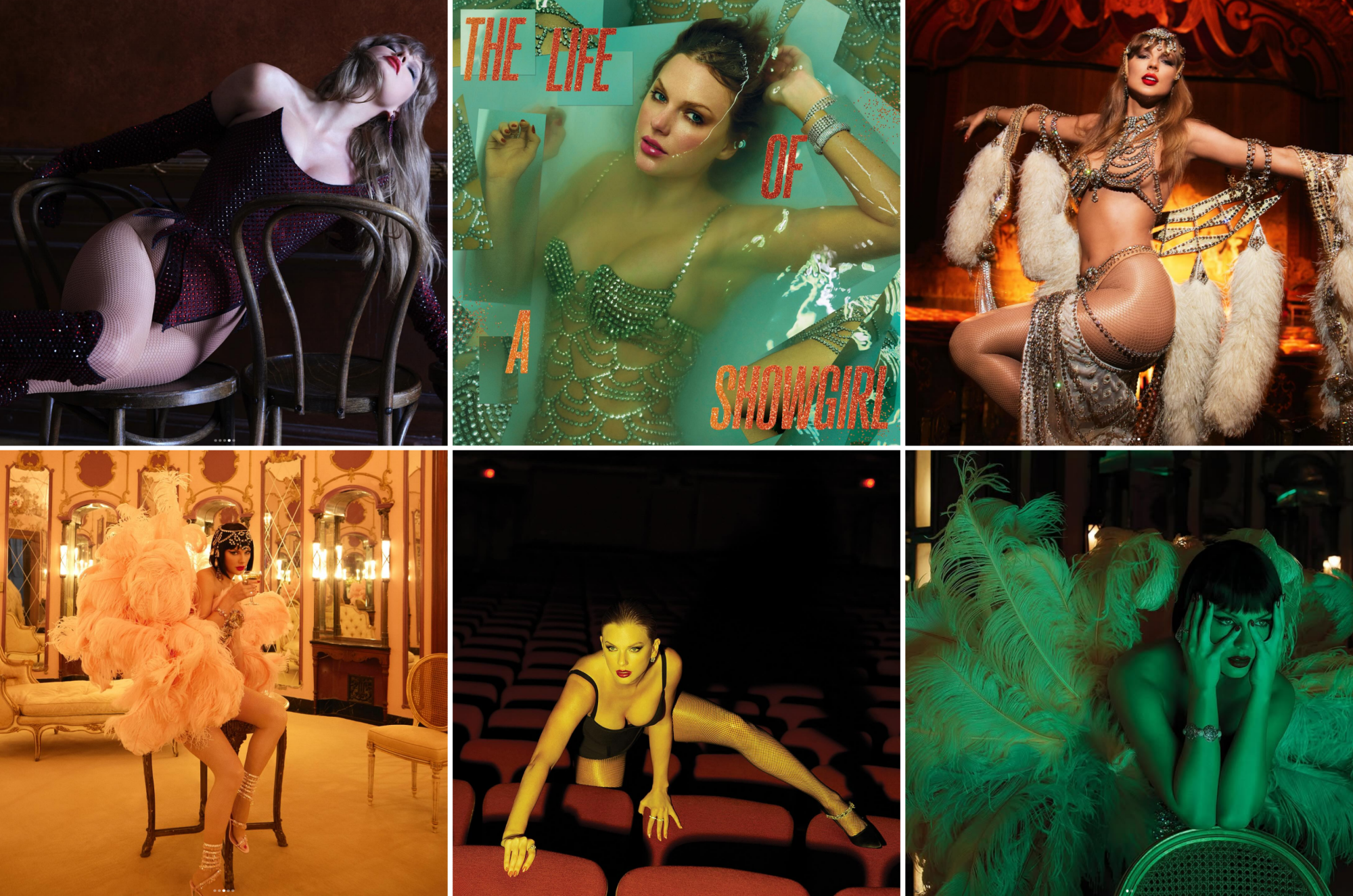

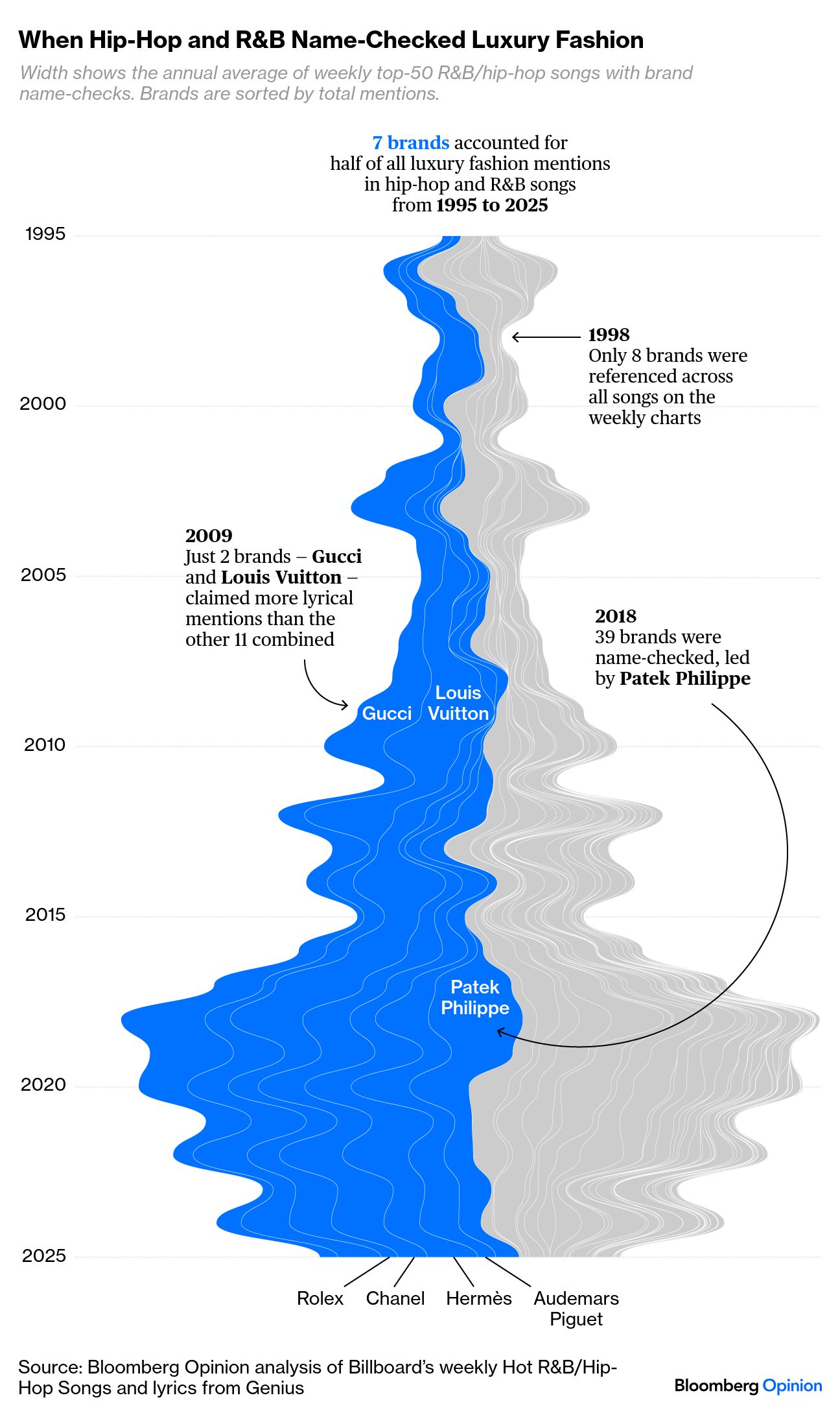

| The day after a Taylor Swift album announcement is always a circus, but The Life of a Showgirl has opened the zoo gates like never before. Everyone is sleuthing around for Easter eggs after last night's reveal — on a sports podcast, no less! — about the pop star's latest project, which contrary to what you might have heard, is not a loaf of cinnamon swirl sourdough bread. Swift's 12th studio album appears to be her flashiest yet, and fans are already fawning over the fashion moments of her showgirl era. On the cover, she's dripping in diamonds in a bathtub, and other images show her paying homage to burlesque dancers in Vegas. Of course, people already want to know where to buy her looks.  Source: Taylor Swift via Instagram Throughout her career, Swift's style has remained a fixation for fans. The clothing and accessories she wears — to a football game, on stage, at a party — can quite literally change a designer's career. But beyond Taylor Swift, do pop culture moments actually matter for companies in the long run? It's a question that Andrea Felsted and Carolyn Silverman have been pondering for quite some time. After poring over decades of Billboard Hot 100 and Hot Hip-Hop/R&B charts, they have an answer: Yes, music does affect the trajectory of the luxury industry. Specifically, song lyrics can be a "useful complement to more traditional measures of brand buzz, such as Google searches and social media conversations," they write. Although Swift name-checks a handful of labels in her songs — "Louis V" and "Stella McCartney" are in London Boy, for instance — hip-hop and R&B artists are far better known for calling out luxury brands. There's a reason for that, Andrea and Carolyn note: "The rap community has long aspired to own top-end goods, and yet many European houses were famously reluctant to embrace streetwear. That changed a decade ago when LVMH appointed the late Virgil Abloh, the founder of influential label Off-White." The shift makes for a striking visual:  In a fascinating twist, the rise and fall of lyrics mentioning brands tracks with the broader economy: "As inflation and interest rates began soaring post-Covid, many of the new luxury customers came under pressure. Big bling retrenched and refocused its attention on older, wealthier shoppers, offering plainer styles and fewer logos. Streetwear faded from fashion and 'quiet luxury' was born." That meant higher-end brand names were appearing less often in lyrics in 2022 and 2023. Gucci is a great example of this. "The label has struggled to redefine itself since [Alessandro] Michele's departure in late 2022, and in tandem, mentions in songs have languished," they write. Looking at these beautifully complex data visuals — and there are so many more in the feature — I can't help but think that Andrea and Carolyn are the true masterminds of our time. They even made a Spotify playlist, just like you know who! Howard Chua-Eoan must have ESP, because he wrote an entire column about the rotisserie chicken renaissance on the same day that Eleven Madison Park's Daniel Humm announced his restaurant would no longer be vegan-only. Bird flu, be damned! Chicken — and meat in general — is having a major moment in 2025. The Trump administration is all aboard the beef tallow train. Parents are feeding their babies puréed chicken liver. And the most romantic thing about The Summer I Turned Pretty is Conrad Fisher's obsession with unseasoned chicken breasts: "After fish, chicken and poultry are our largest sources of animal protein. About 70 billion birds are slaughtered each year by a global industry that churns their meat through a market projected to be worth $375 billion in 2030," Howard writes. Can farmers handle the poultry craze? "The system is fragile — as the ongoing global struggle with H5N1 is showing. … Globally, more than half-a-billion farmed birds — including chickens — have been culled to prevent even greater catastrophe," Howard explains. And don't get him started on the labels: "Everything is compromised, even in the relatively more principled free-range world, where most people assume chickens have the right to roam. Until mid-May, the UK had guidelines in place to keep free-range and organic birds indoors" because of the bird flu. "Even without a health emergency, regulations sometimes allow farmers to confine free-range birds indoors in barns for half their lives, which — at an average of eight weeks — isn't much longer than an industrial broiler's," he writes. I regret to inform you that non-organic, plain old regular chickens are killed in just five weeks — a cruel, barely existent life for our little feathered friends. |

No comments