| Entering this year, American Exceptionalism was all the rage. Then the narrative turned to the Great Retreat from America, as Trump 2.0 proved far more aggressive than Trump 1.0. The US couldn't be trusted, went the new story, and international investors needed to yank their funds as the country turned into a banana republic. Now, tariffs have settled right at the top of the range that seemed possible six months ago. Americans will pay an average effective tariff of 19% on their imports. And the president, empowered by a string of victories, has resorted to possibly his most banana-republic move yet by firing his head of labor statistics because he didn't like the latest jobs numbers. There's been little or no market riposte. Does this mean that Exceptionalism lives? Or that the Bananafication narrative was overdone? As ever, the truth is nuanced. Elements of both are true, but the critical variable may be on US defense policy. Tariffs are higher than expected, but the US has held off on going the full isolationist route. For the dollar and capital flows, that possibly matters even more than tariffs. The exceptionalism story peaked at the turn of the year, when the dollar was hugely expensive. On the Federal Reserve's real and broad index, the sharp pullback does no more than remove post-election froth. The dollar remains expensive: The US net international investment position (the gap between foreign holdings of US investment and American investments overseas) remained very negative at Liberation Day, when the International Monetary Fund last revised its figures: A chart of the stock market compared to the rest of the world tells a similar story. After extreme outperformance around the election, the pullback early this year now looks more like a needed correction than a changed trend. US stocks have held the lead since April. They still command a big premium. The mega caps that benefit from investments in artificial intelligence have much to do with this, but the premium remains even when the Magnificent Seven tech stocks are excluded: Again, the excitement earlier this year begins to look like simply trimming excess. US companies remain far more expensive than their international counterparts, even though they're the ones that will mostly have to pay the new tariffs. This isn't normal. Contrary to current perceptions, US stocks haven't always traded at a premium to everyone else. If we use cyclically adjusted price/earnings multiples, a good long-term metric, as calculated by Barclays, the premium is relatively recent: After the first-quarter drama, which culminated with the the initial imposition of tariffs on April 2, there could have been a much greater flow out of the US, which didn't happen. Why not? Let's use a framework from Fathom Consulting of London. There is an obvious global imbalance, with the US borrowing from the rest of the world and leaving everyone else exposed to American stocks and bonds. Fathom suggests three ways to deal with this: - The creditors (like Germany) can start investing and spending more.

- The debtors (the US) can pull in their horns, with tighter fiscal policy and less consumer spending.

- Financial flows can do the job; if foreign investors pull money from the US, that brings down US asset values and the dollar, eliminating the imbalance.

A fourth option is not to deal with it. The most likely outcome is a combination of all four. So far, Germany's fiscal expansion is big progress on 1), while the tax cuts in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act suggest 2) will have to wait. A big shift in asset markets started, but has been on pause for about three months. By firing his chief statistician, the president has gone out of his way to undercut international confidence and bananafy the US, so why has this halted? The chief point, according to Fathom's Kevin Loane, is that reserve currencies are tightly linked to security relationships — and Trump has pulled back from the extreme isolationism he initially espoused. Loane cites this paper by the University of California Berkeley's currency expert Barry Eichengreen. He showed: Countries that rely on the US for their security umbrella are disproportionately inclined to hold dollar reserves. A scenario where the US withdraws from the global stage results in about a 30 percentage-point reduction in the share of the dollar in the reserves of US-dependent states (assuming the level of global reserves remains unchanged). Six percent of US marketable public debt is liquidated, while long-term US interest rates increase by as much as 80 basis points.

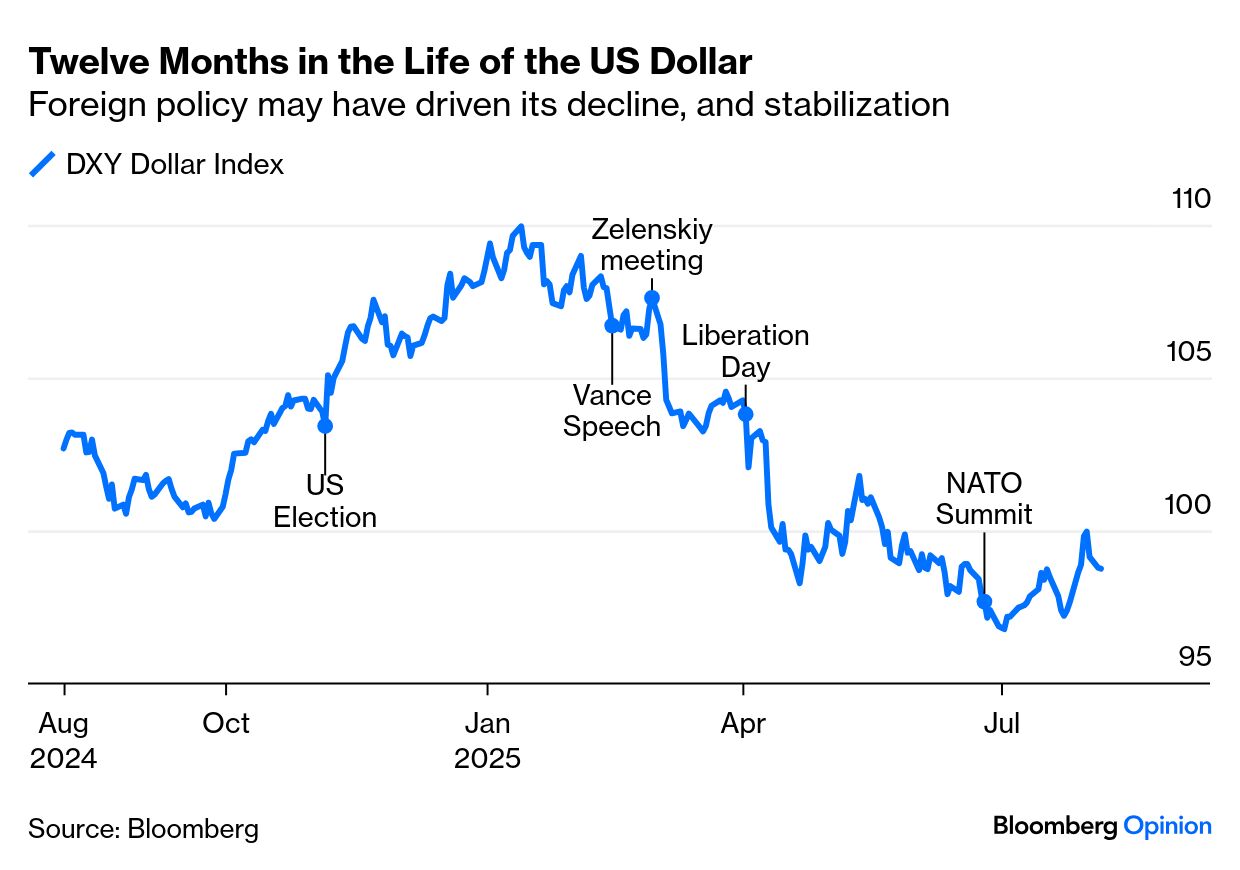

The dollar's movements this year have been entwined with defense. The currency tanked almost as much after the president humiliated his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelenskiy (prompting Germany's massive turnaround on defense policy) as it did after the Liberation Day tariffs. At that point, it appeared the US might no longer be an ally at all. After the June NATO summit where America's allies agreed to raise their defense budgets, the dollar stabilized. Still a member of NATO, Trump is now taking a far more aggressive approach toward Vladimir Putin and Russia, and reserves can stay safely in the US:  Alternatively, take Trump's plans to annex Greenland and the Panama Canal, neither of which had featured in his campaign. Such crude imperialism horrified the rest of the planet. A count of stories from all sources appearing on the Bloomberg terminal shows that territorial expansion left the agenda in April. That's great news for Panamanians and Greenlanders, and also holders of the dollar: If the rest of the world has a strategy (as opposed to a lack of will for the fight), it is to give Trump what he wants in return for retaining his military support, and wait for protectionism to blow up in his face. The global economy takes some pain but probably avoids a recession. If he desists from territorial expansion ambitions, so much the better. If that is the plan, it has a decent chance of working. |

No comments