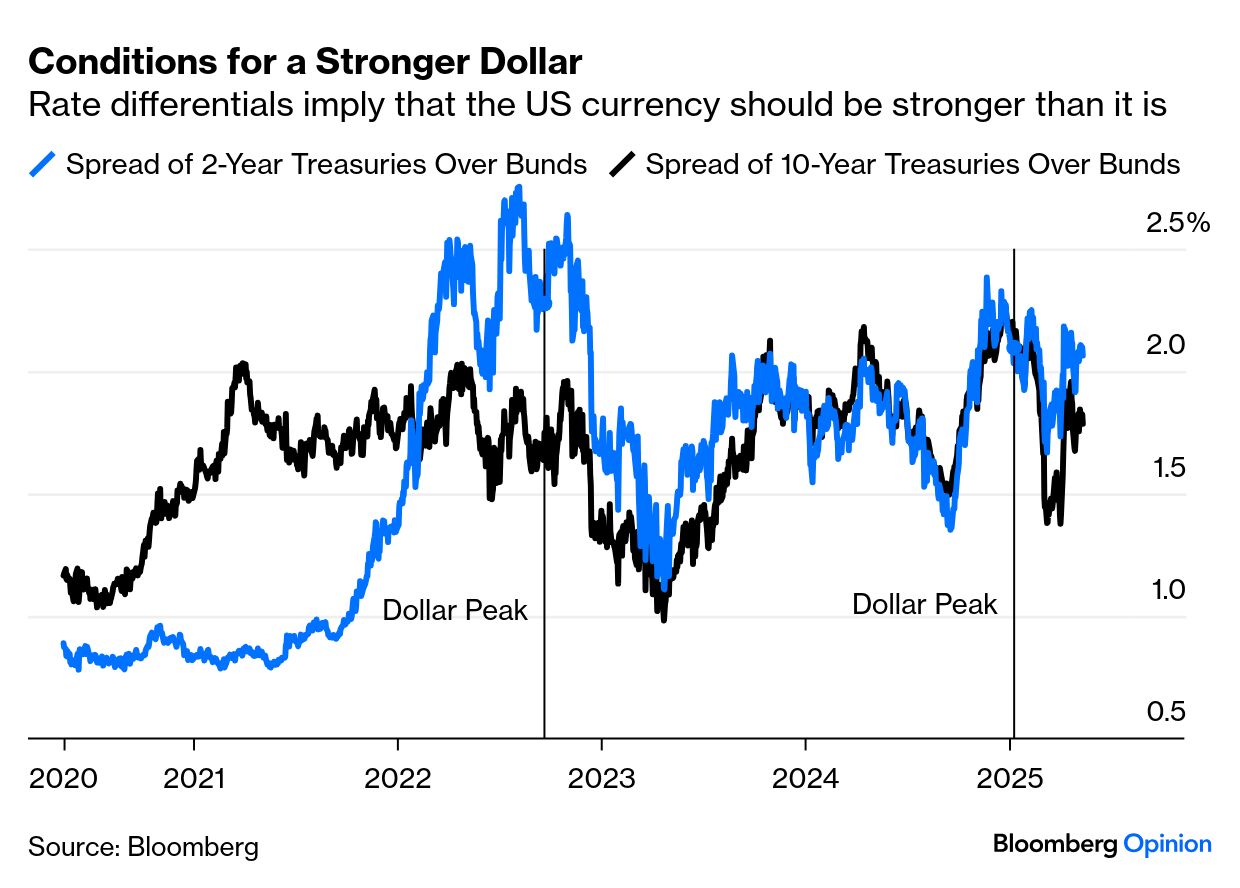

| The dollar's reign as global reserve currency was established in 1944 through the Bretton Woods agreement, and it's not over. However, President Donald Trump's economic nationalism agenda has done some damage to its value. The index tracking the greenback against its peers is down by over 8% since January. It enjoyed a 1.35% gain on Monday's 90-day truce between China and the US, but the news of cooling inflation piled on to its woes. Ordinarily, a third successive month of weaker inflation than expected would inspire confidence that the Fed could ease — but this is counterbalanced by relief that the threat of a recession, which would force rate cuts, is also receding. For now, fed fund futures are still pricing in at least two rate cuts by year-end. That's less aggressive than expectations for other central banks, and so the differential of US yields compared to German equivalents has risen back near the top of its range:  Paul Mackel, HSBC's global head of FX research, argues that as traditional drivers such as rate differentials suggest a stronger dollar, the fact that the currency isn't putting together more of a recovery tells us that other forces are dominating, and that there is an ongoing lack of trust. Equities may have made good their losses for the year, but the dollar is nowhere near that: Paul Donovan, chief economist of UBS Global Wealth Management, argues that it's a stretch to see the dollar losing reserve status. A more realistic worst case sees the dollar losing market share as global trade declines: If there is less global trade, there is less need to hold reserves, and there's less need for international investors to buy Treasuries. That's an underlying trend. It doesn't mean the Treasury bond market collapses, but it does mean the ability to fund cheaply is called into question over the next few years.

That ongoing de-dollarization opens up various opportunities outside of the US. Themos Fiotakis, Barclays head of FX strategy, doesn't see many credible candidates ready to fully exploit the structural weakness that has emerged: Can the US stop presenting a good opportunity in corporate profitability, and could a rival investment destination rise? It can, but it's hard to see this happening on the back of tariffs alone, or as a result of some kind of independent capital flow decision. It is, to us, a much deeper and much more fundamental investment question.

Gold's run to fresh records this year can be viewed as part of the "get out of the way of a dying dollar" trade, and an astonishing number of fund managers in the BofA survey now think that the metal is overvalued. With traders now retreating a little, that's another sign that the dollar's recent weakness has been overdone: The dollar's direction from here depends on cyclical, political and structural factors. HSBC's Mackel argues that it's on soft ground, but not on the verge of a multi-year decline: The cyclical component is not obviously USD negative if the US and global economy are slowing. The political/policy factor has been weighing on the USD, albeit not in the same manner lately. Yet, we are reluctant to think the policy uncertainty is no longer a burden to the USD. On the structural side, much will rest on the US economic outlook and how the Fed responds in the months ahead. This will determine if the de-dollarization theme has real potential via changing FX hedging behavior and more.

Mackel concedes that trust in the greenback has taken a hit, and will need time to restore. That's because critical characteristics for a reserve currency — including, Donovan argues, the rule of law itself — have been called into question. That doesn't mean that the euro or yuan will take over. But it does suggest a steady decline in the dollar's market share, following a trend that's been in place since the Global Financial Crisis, and a weaker dollar over time. —Richard Abbey |

No comments