Inflation still matters more than anything

Since the last consumer price inflation numbers for the US just a month ago, the

political landscape has turned on its head and global markets have endured their

biggest scare since the pandemic. So it can be difficult to remember that the

inflation numbers due Wednesday still matter a lot. For markets, they arguably

matter more than anything else.

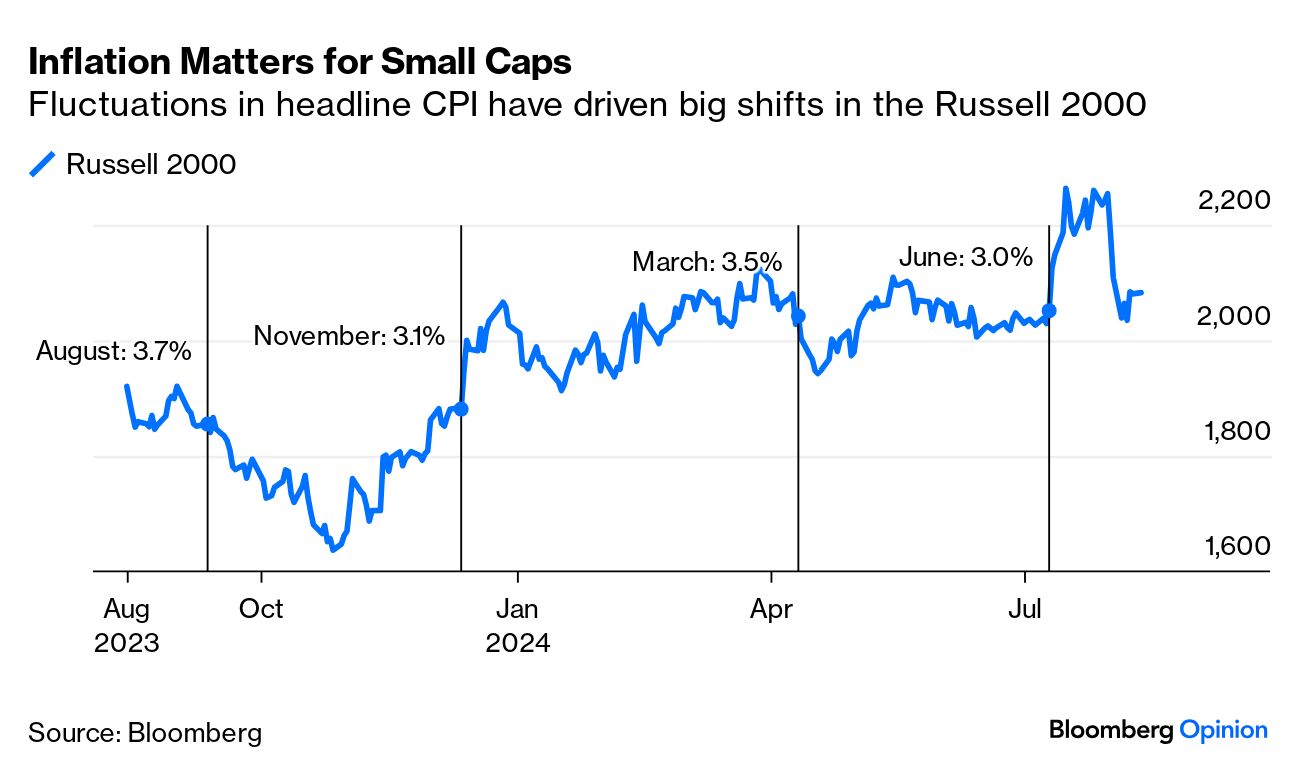

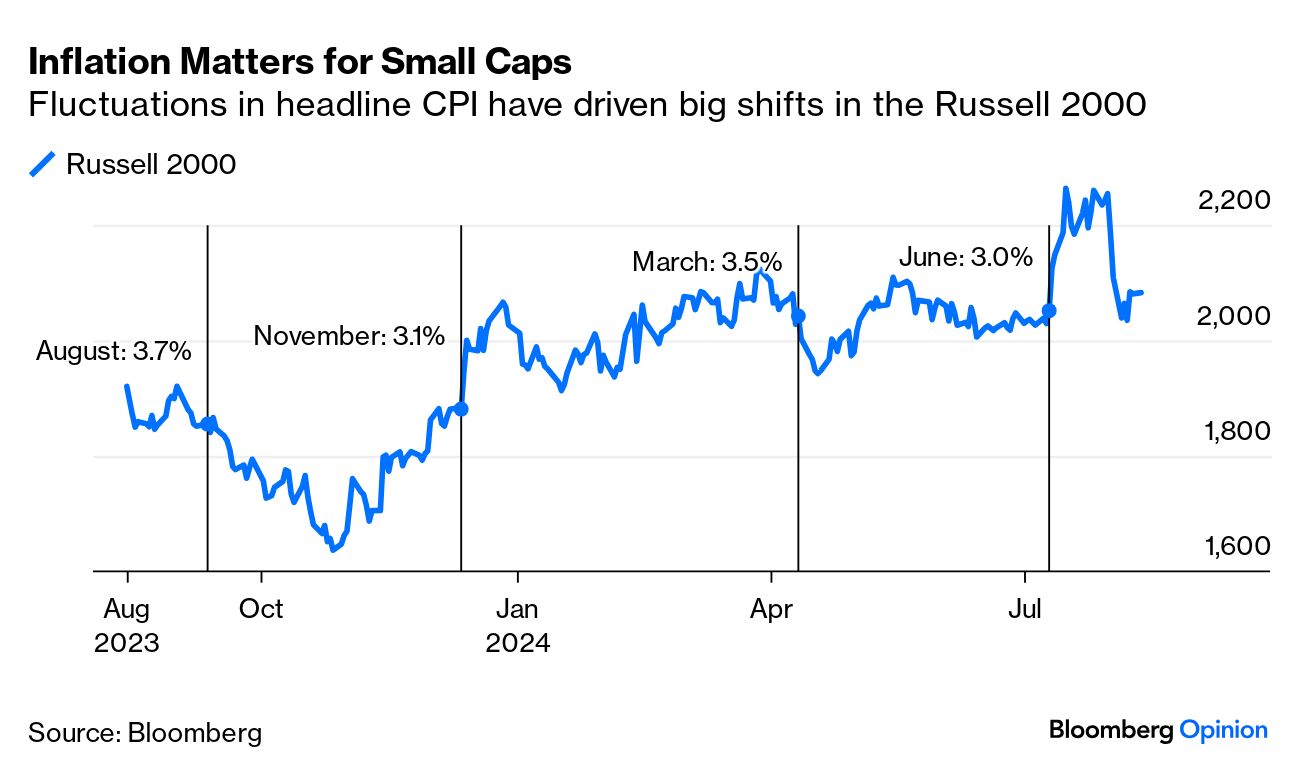

To get a flavor of that, this is how the Russell 2000 index of small-cap stocks has moved over the last year. It's not a coincidence that all the biggest turns with the exception of last week's swoon came on days when surprising Consumer Price Index data were published:

Inflation matters to the stock market chiefly through its impact on interest rates and monetary policy. Lower interest rates mean that future profits can be discounted at a lower rate. It's therefore not a surprise that the Russell was held back by discomfitingly high inflation numbers (implying rate cuts wouldn't come quickly), and rallied on surprisingly low numbers.

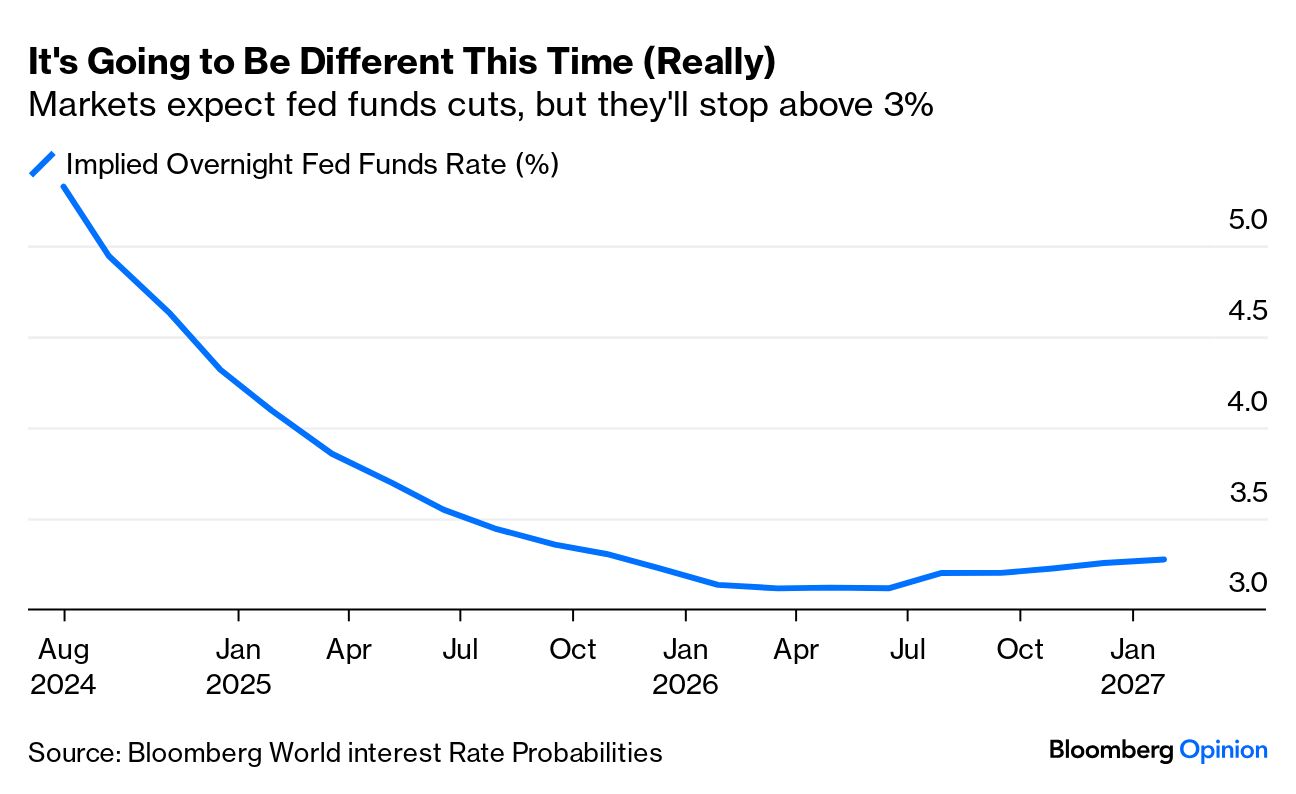

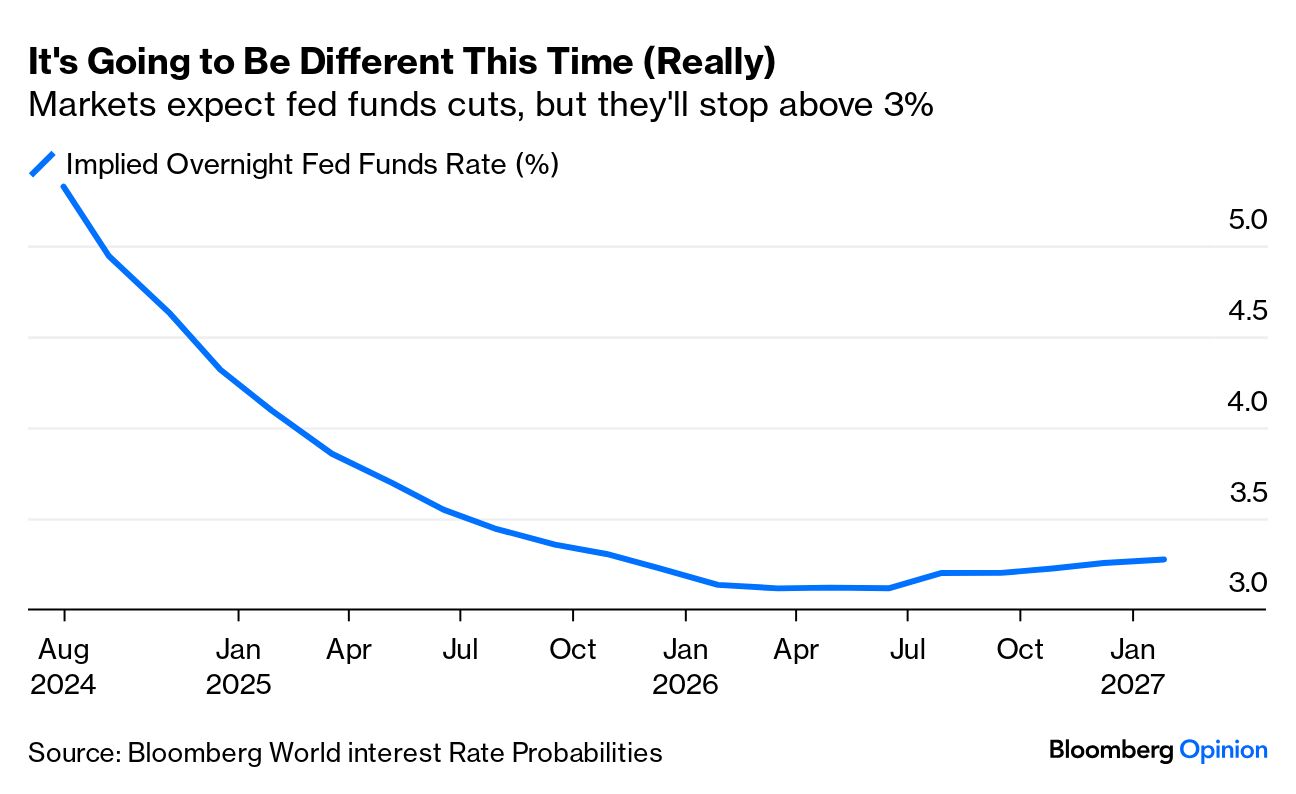

Rate expectations, meanwhile, have found their way to an interesting place. The Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function is now able to generate implicit forecasts for the fed funds rate through to the beginning of 2027. It shows high confidence that the next year or so will be devoted to a significant easing that will see the overnight rate fall by at least two percentage points:

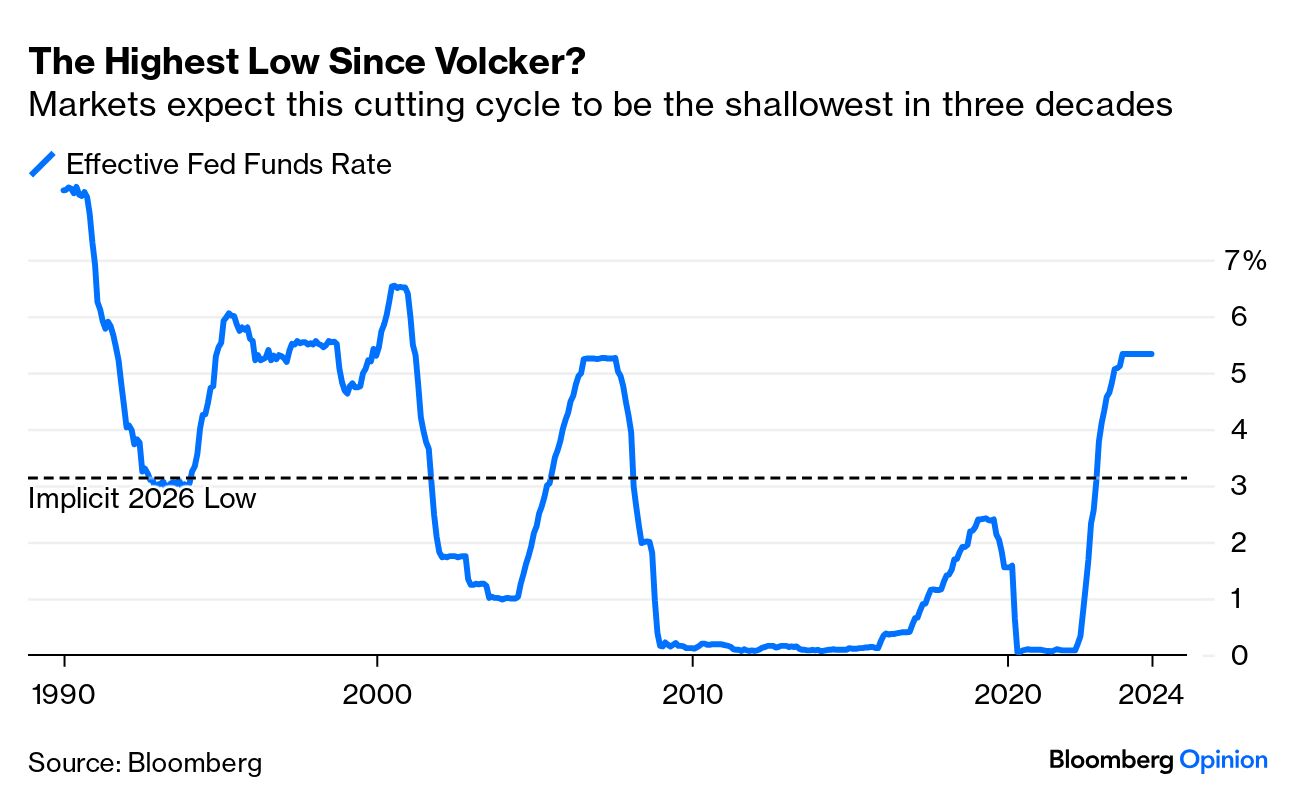

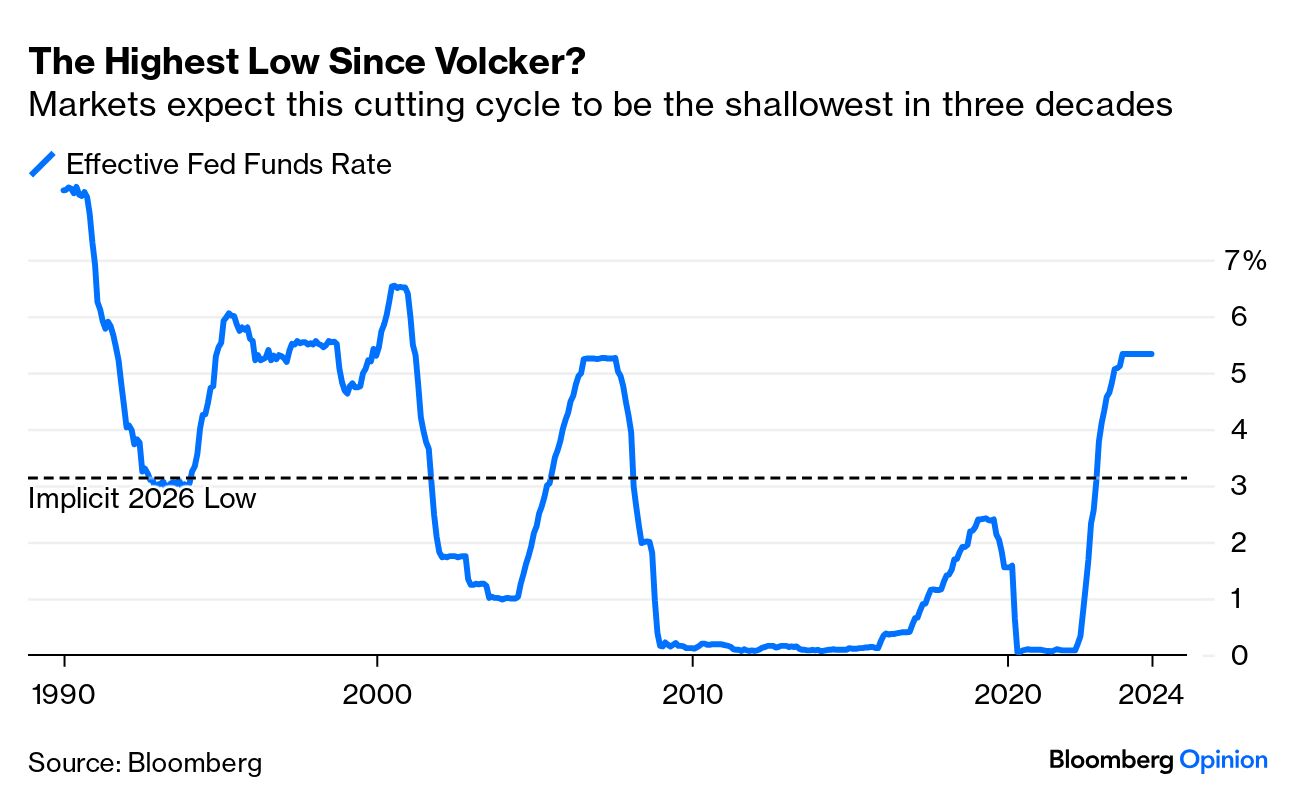

That would be a big change, and a higher inflation figure this week would shake the current certainty. But perhaps just as interesting is that, at least for now, the fed funds futures market sees the rate-cutting cycle ending and hitting bottom above 3%. Since Paul Volcker stood down as Federal Reserve chairman in 1987, the low of the effective fed funds rate in each cycle has always been below 3% (a level it only just reached during Alan Greenspan's first big cutting cycle in the early 1990s). So even if markets buy the notion that the Fed will have to cut soon, they also seem convinced by the theory that the very low rates of the last three decades were an aberration, and that the norm for monetary policy will be tighter in future. That presumably goes hand-in-hand with slightly higher inflation rates:

If the money markets appear convinced by an imminent cyclical fall in rates, they seem similarly convinced for now of a secular rise. Normality following the dot-com bubble, the Global Financial Crisis and the pandemic, they appear to believe, is coming back.

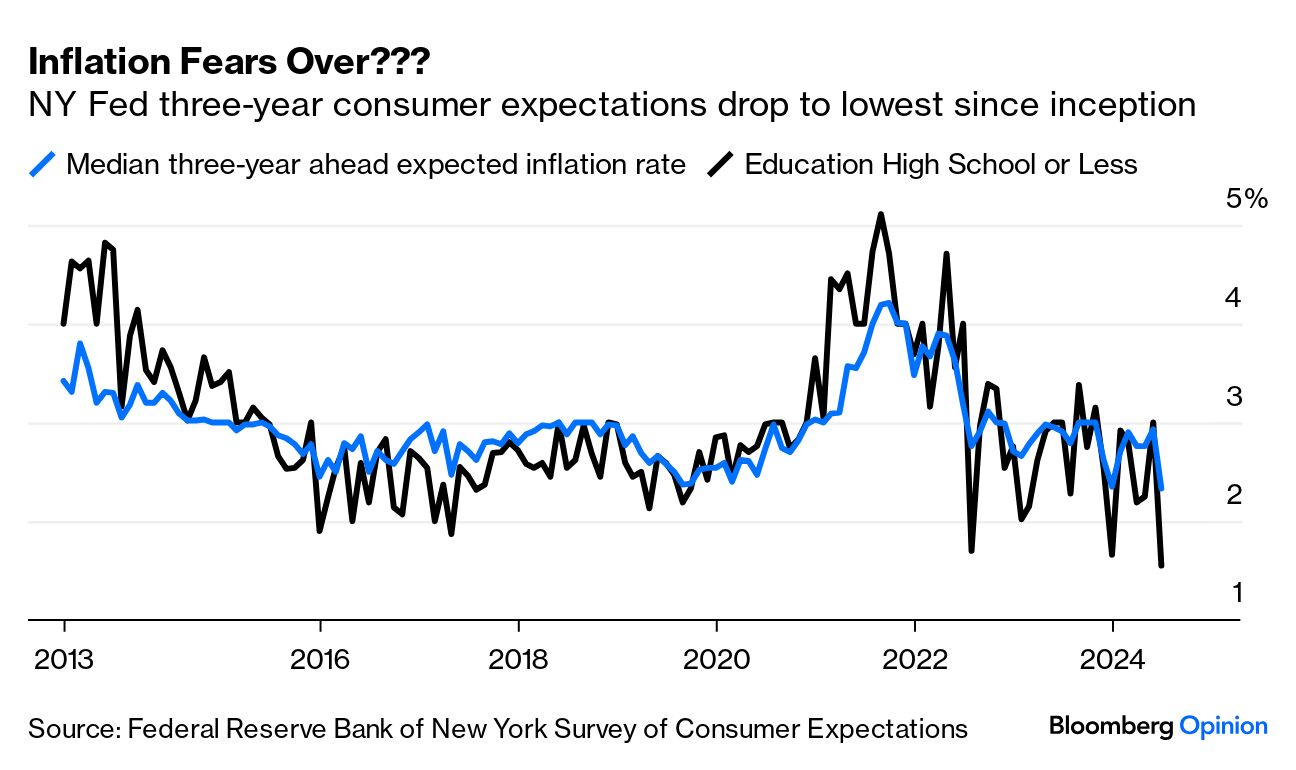

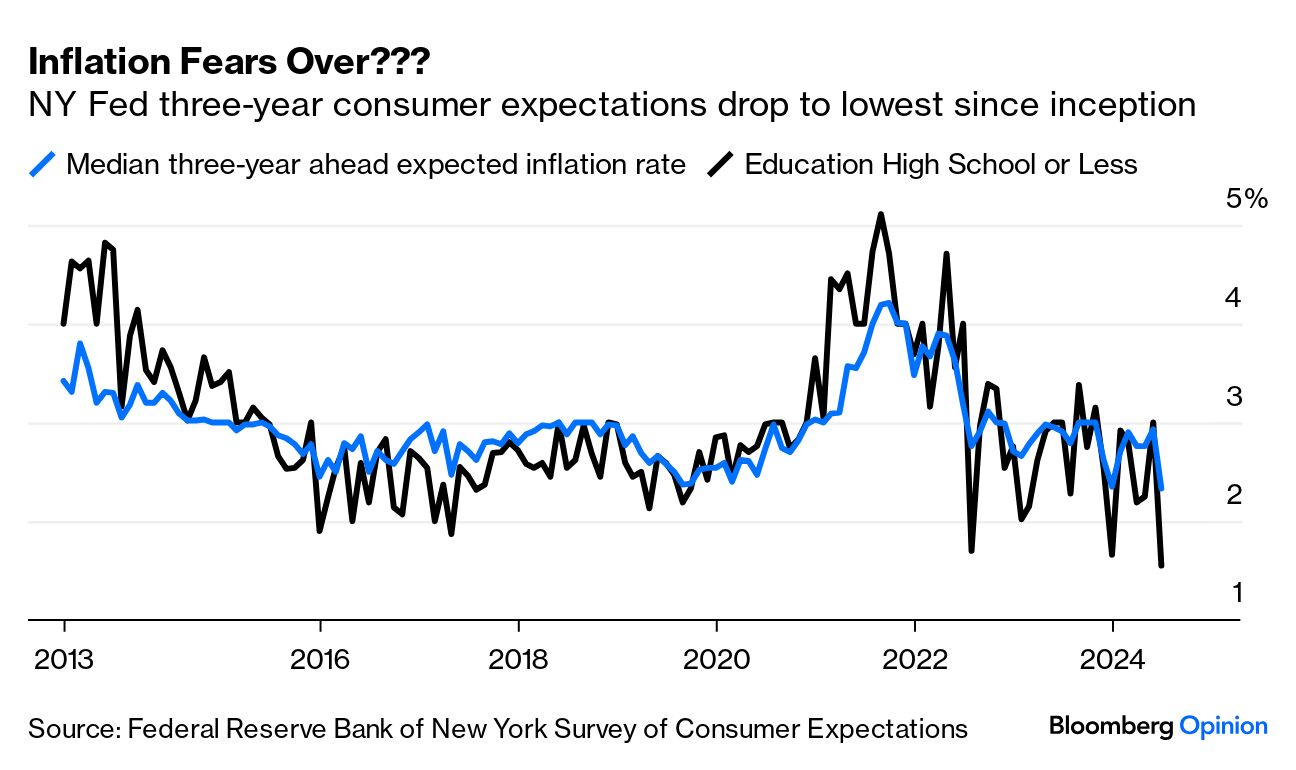

What's perhaps surprising is that consumers are now overcoming their fears of inflation. Monday saw the publication of the New York Fed's regular survey of consumer expectations, which is very closely watched by the policy-setters on the Federal Open Market Committee. The figures for three-year inflation were very surprising; the lowest expectations since the start of the survey in 2013, with the fall most marked among those whose education ended at high school or earlier (who generally suffer more harm from inflation than others):

There were no methodological chances last month that might explain the sudden dip. A fluke, or "noise," in the data is always possible, but we'll need to wait for next month's survey to get any light on this. On its face, it suggests that consumers are suddenly very confident that inflation is coming down. The fact that the least-educated seem most optimistic is also, if this number isn't a fluke, a very positive indicator for the Democrats in the November election. Shifting political probabilities might also change expectations on inflation and rates.

Turning to market expectations for the next three years, the breakeven level (where fixed-rate and inflation-linked yields would turn out equal) has also dipped frantically. It's currently below 2%, which happens to be the Fed's target, at a post-pandemic low:

All of this is consistent with a world in which the Fed decisively reassumes control and drives a soft landing with which all can be comfortable. As more or less nobody truly appears to expect this outcome in their heart of hearts, judging by the commentary whirling from all sides, the implied risks of surprises are real.

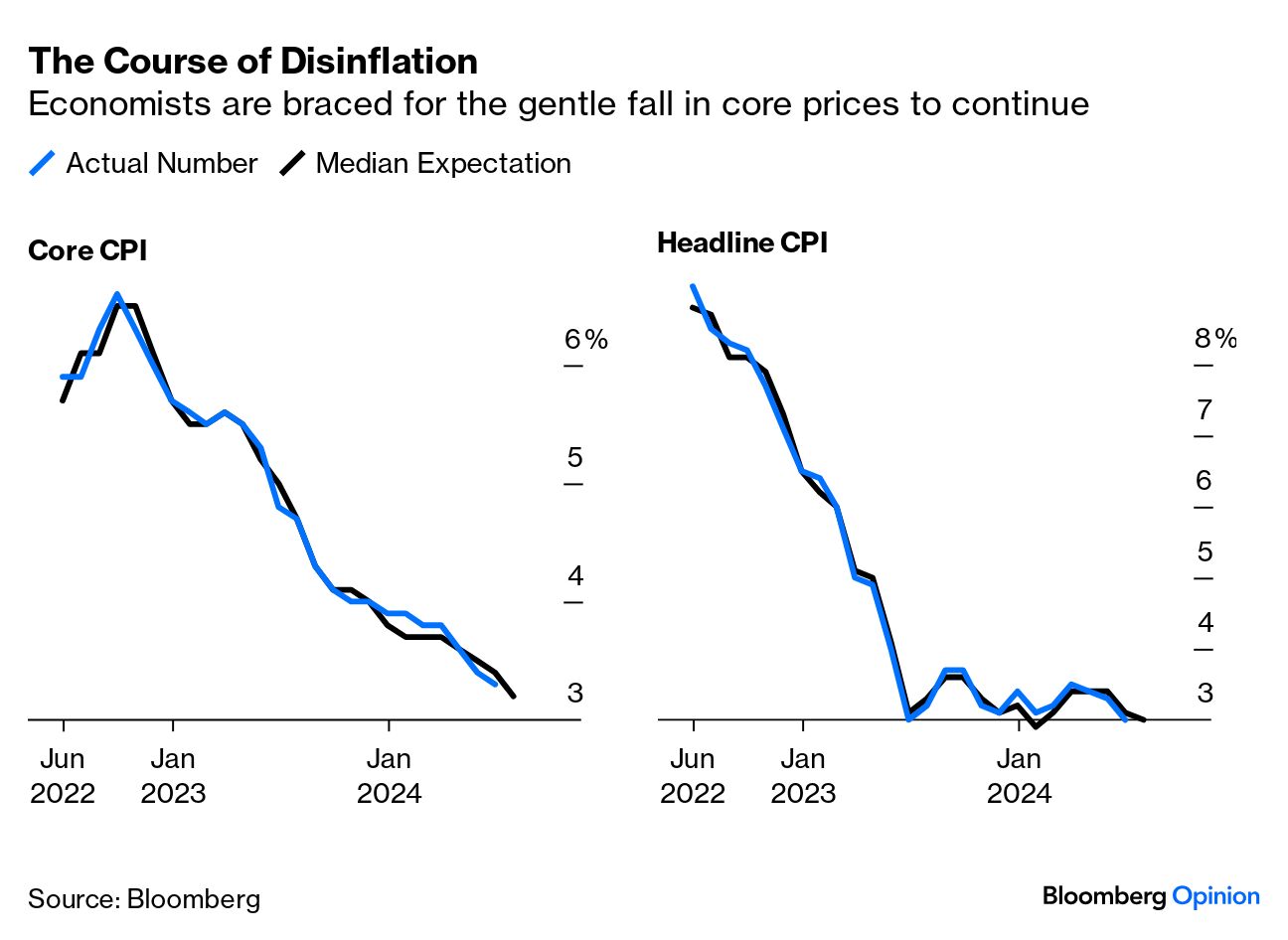

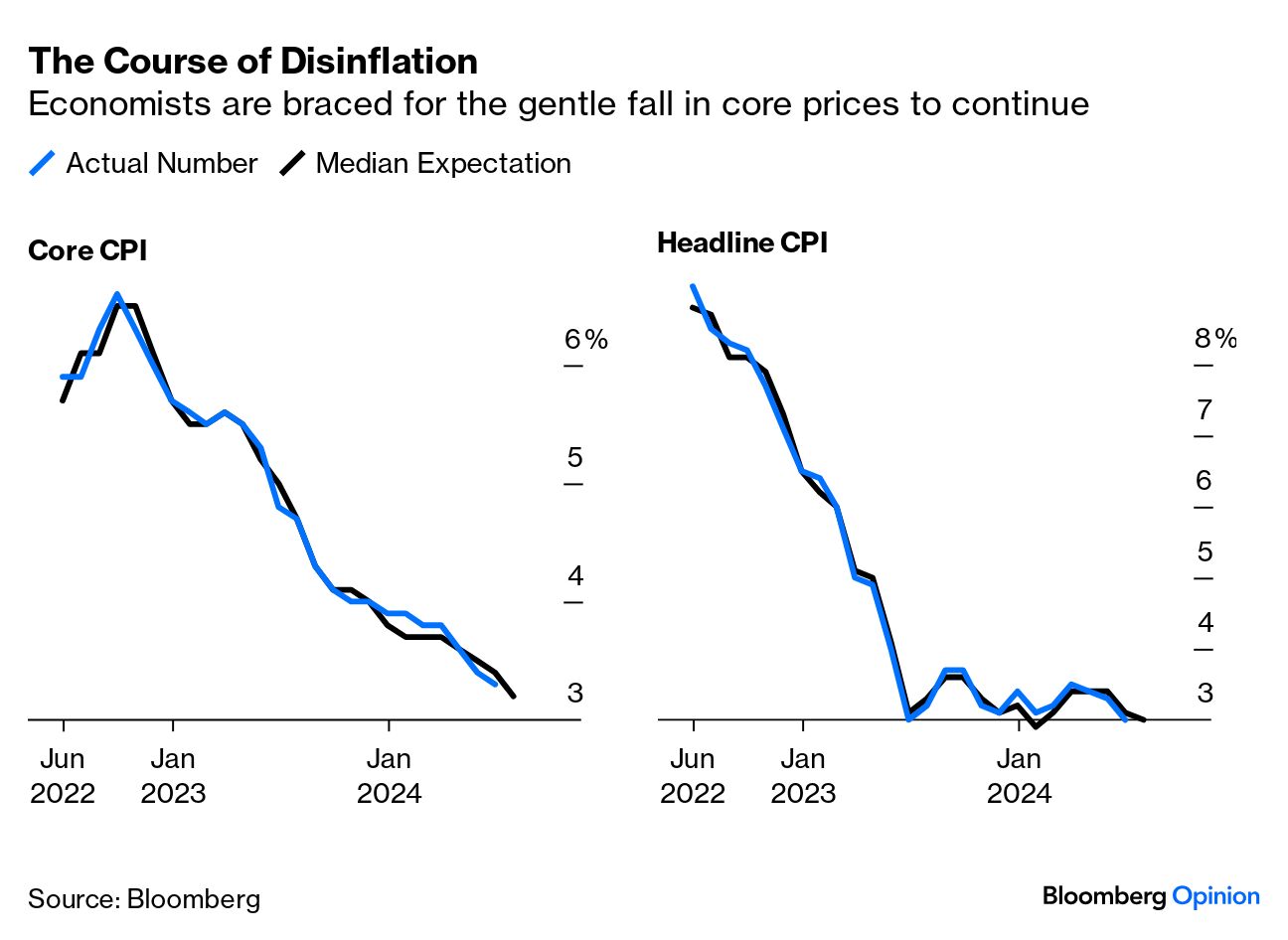

That brings us to Wednesday's CPI numbers (which follow producer price data on Tuesday). Economists polled by Bloomberg expect another slight fall for the core figure, while the headline (less important for monetary policy) will be roughly flat:

If fulfilled, the markets can be expected to continue to calm down after their recent seizure. An upside surprise could be difficult to handle. A rate cut next month is currently priced as a certainty. Talk of an intra-meeting cut, prevalent last week, has lightened up, but a September easing is still priced as a certainty, with a big 50-basis-point cut viewed as a 50/50 shot. Will Denyer, US economist for Gavekal Research, argues:

Investors are so certain that the Federal Reserve is all set to make aggressive cuts in interest rates that if July's CPI release this Wednesday comes in higher than expected, the markets could be in for a nasty shock. Although a September rate cut is the base case, the danger is that an uptick in inflation on Wednesday could trigger a violent position adjustment.

He also dismissed as "wishful thinking" arguments that weakening labor markets ensured a September cut regardless of inflation. Sentiment has swung several times already this year on the chance of rate cuts. This isn't a prediction, but there is time for it to change again. (The same is true, incidentally, of the US election campaign.)

To get a flavor of that, this is how the Russell 2000 index of small-cap stocks has moved over the last year. It's not a coincidence that all the biggest turns with the exception of last week's swoon came on days when surprising Consumer Price Index data were published:

Inflation matters to the stock market chiefly through its impact on interest rates and monetary policy. Lower interest rates mean that future profits can be discounted at a lower rate. It's therefore not a surprise that the Russell was held back by discomfitingly high inflation numbers (implying rate cuts wouldn't come quickly), and rallied on surprisingly low numbers.

Rate expectations, meanwhile, have found their way to an interesting place. The Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function is now able to generate implicit forecasts for the fed funds rate through to the beginning of 2027. It shows high confidence that the next year or so will be devoted to a significant easing that will see the overnight rate fall by at least two percentage points:

That would be a big change, and a higher inflation figure this week would shake the current certainty. But perhaps just as interesting is that, at least for now, the fed funds futures market sees the rate-cutting cycle ending and hitting bottom above 3%. Since Paul Volcker stood down as Federal Reserve chairman in 1987, the low of the effective fed funds rate in each cycle has always been below 3% (a level it only just reached during Alan Greenspan's first big cutting cycle in the early 1990s). So even if markets buy the notion that the Fed will have to cut soon, they also seem convinced by the theory that the very low rates of the last three decades were an aberration, and that the norm for monetary policy will be tighter in future. That presumably goes hand-in-hand with slightly higher inflation rates:

If the money markets appear convinced by an imminent cyclical fall in rates, they seem similarly convinced for now of a secular rise. Normality following the dot-com bubble, the Global Financial Crisis and the pandemic, they appear to believe, is coming back.

What's perhaps surprising is that consumers are now overcoming their fears of inflation. Monday saw the publication of the New York Fed's regular survey of consumer expectations, which is very closely watched by the policy-setters on the Federal Open Market Committee. The figures for three-year inflation were very surprising; the lowest expectations since the start of the survey in 2013, with the fall most marked among those whose education ended at high school or earlier (who generally suffer more harm from inflation than others):

There were no methodological chances last month that might explain the sudden dip. A fluke, or "noise," in the data is always possible, but we'll need to wait for next month's survey to get any light on this. On its face, it suggests that consumers are suddenly very confident that inflation is coming down. The fact that the least-educated seem most optimistic is also, if this number isn't a fluke, a very positive indicator for the Democrats in the November election. Shifting political probabilities might also change expectations on inflation and rates.

Turning to market expectations for the next three years, the breakeven level (where fixed-rate and inflation-linked yields would turn out equal) has also dipped frantically. It's currently below 2%, which happens to be the Fed's target, at a post-pandemic low:

All of this is consistent with a world in which the Fed decisively reassumes control and drives a soft landing with which all can be comfortable. As more or less nobody truly appears to expect this outcome in their heart of hearts, judging by the commentary whirling from all sides, the implied risks of surprises are real.

That brings us to Wednesday's CPI numbers (which follow producer price data on Tuesday). Economists polled by Bloomberg expect another slight fall for the core figure, while the headline (less important for monetary policy) will be roughly flat:

If fulfilled, the markets can be expected to continue to calm down after their recent seizure. An upside surprise could be difficult to handle. A rate cut next month is currently priced as a certainty. Talk of an intra-meeting cut, prevalent last week, has lightened up, but a September easing is still priced as a certainty, with a big 50-basis-point cut viewed as a 50/50 shot. Will Denyer, US economist for Gavekal Research, argues:

Investors are so certain that the Federal Reserve is all set to make aggressive cuts in interest rates that if July's CPI release this Wednesday comes in higher than expected, the markets could be in for a nasty shock. Although a September rate cut is the base case, the danger is that an uptick in inflation on Wednesday could trigger a violent position adjustment.

He also dismissed as "wishful thinking" arguments that weakening labor markets ensured a September cut regardless of inflation. Sentiment has swung several times already this year on the chance of rate cuts. This isn't a prediction, but there is time for it to change again. (The same is true, incidentally, of the US election campaign.)

No comments