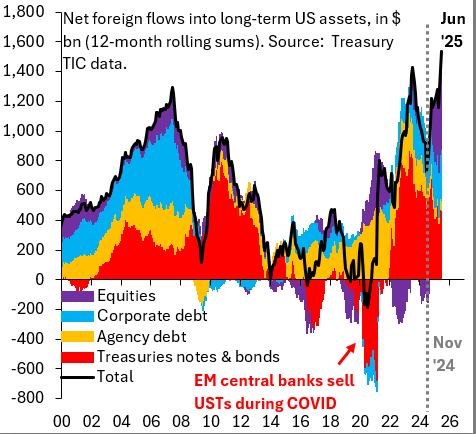

| As the world's central bankers gather in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for their annual dose of fresh air in the shadow of the Tetons, they can sense the plates beneath them are beginning to shift. This will definitely be Jerome Powell's last symposium as chairman of the Federal Reserve, his Last Stand in the Wild West. The drama surrounding his replacement threatens to become all-consuming. Profound changes for the Fed, to be imposed by others, are on the agenda. But it's also an opportunity for a profound change in the direction that the Fed decided on for itself five years ago, in what now appears to be a spectacularly ill-timed intervention. It was at Jackson Hole in 2020 that Powell unveiled Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT), which would aim to keep inflation to an average of 2%, rather than treat 2% as an upper limit. Points of Return ridiculed this at the time. The Fed's fear then was of Japanification, and an approach that allowed the economy to run a little hot from time to time seemed better. It seemed like wishful thinking — the economy had been sluggish for decades, and such a move seemed like pressing on the accelerator of a feeble car whose engine wasn't powerful enough to break the speed limit. As it turned out, within months Japanification would seem the least of the Fed's worries. Inflation has averaged far more than 2% over the last five years, Powell and his colleagues have taken the blame for a big mistake, and the central bank's credibility needs to be regained. There is apparently no chance that the 2% target will be abandoned, even though the political pressure to cut rates would imply that the Trump administration feels happy to live with prices rising at a somewhat faster clip. Powell's swan song at Jackson Hole could end on a sour note — or perhaps as a defiant last stand in the same state (then a territory) where Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer met his end in 1876.  Powell finds himself in a Hole. Source: Bloomberg If he does hold firm against the pressure on him to cut rates, that could create as much excitement as a typical Western. Rates markets, as monitored by the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function, have moved to discount a far more drastic easing over the last six months, a period in which inflation has started to rise again: This sets markets up for a hawkish surprise. The near-term speculation looks particularly overdone. The futures market suggests that the odds of a 25-basis-point cut next month are about 85%. But there are a lot of wagers on a "jumbo" cut of 50 basis points. My colleague Edward Bolingbroke points out that open interest in secured overnight financing rate options that would deliver a big profit if the Fed made a jumbo cut of more than 25 basis points have exploded in the last two weeks. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent argued last week that the Fed should consider a jumbo cut, and also that rates should be at least 150 basis points lower. The market currently is behaving as though he's likely to get what he wants. The main reason for that comes from the politics of the Fed. Two governors, both of whom have been told they're candidates for the chair, voted to cut last month. Several more members of the Federal Open Market Committee are also now under consideration — and know that they'll need to do the same if they want the job. For now, the race to replace Powell remains wide open, probably because the administration has calculated that this maximizes its chances of getting cuts even while he remains in place. As far as Polymarket is concerned, the marginal favorite is current governor Chris Waller, but there's still a one-in-three chance that no nomination is made this year: The enthusiastic rate-cut bets rest primarily on the theory that the way President Donald Trump and his officials are running the Fed contest will persuade the committee to vote that way. Inflation, which is rising and above target, offers no reason whatever to cut rates. The case for easing rests exclusively on employment, the other side of the Fed's mandate. Handily, this year's Jackson Hole symposium is entitled Labor Markets in Transition: Demographics, Productivity, and Macroeconomic Policy. It will be wrestling with the critical topic of the moment. Evidence from the labor market is contradictory and, of course, marred by unreliable data. Payroll growth is still positive but slowing. Other data paint a confusing picture. According to the New York Fed's quarterly labor market survey, the "reservation wage" — which workers will expect before being prepared to move — has just leapt to an all-time high. That suggests that there's still plenty of potentially inflationary heat: The New York Fed also tracks mobility by asking what has happened to those who were in work three months earlier. The number who have moved on, for whatever reason, has rebounded to a post-pandemic high: When the jobs market churns this much, it's harder to see the macroeconomic signals. Meanwhile, the Atlanta Fed's wage tracker, based on census data, shows wage rises falling but still at levels for the highly skilled that weren't seen for more than a decade after the Global Financial Crisis. Inequality, which became acute during the Obama presidency as wages for low-skilled workers languished, appears to be returning. That's not great for a White House dedicated to reversing inequality. It also implies that falling immigration hasn't yet pushed up wages for the low-skilled: This may be a matter of time. Reliable data on illegal migrant labor is hard to come by, but Banco de Mexico's data show that remittances to the country are now declining, after rising for the better part of a decade (including Trump's first term). That suggests the supply of migrant labor in the US is tighter, which might imply higher wage inflation for the low-skilled: Turning to the consumer, big retailers are now releasing quarterly results. Home Depot offers scant evidence of declining consumer appetite. Revenues are at a record — not something you'd expect at a time when a jumbo cut is needed: Home Depot's sales tend to rally when more people are moving house. The housing market is perhaps the most widely cited reason for the Fed to cut aggressively; houses are very hard to afford, and new building is languishing. Cheaper mortgages might spark this back into life. The latest data show rising housing starts, but new permits, a leading indicator of building activity, dropped to a post-pandemic low: It's a difficult situation. There is a case for a rate cut next month. It's hard on the current evidence to see that market expectations would be anywhere near where they are without the political pressure. Powell's Last Stand (which Julian Brigden of Macro Intelligence Partners points out will take place not so far from the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn) might yet deliver quite a shock. Jackson Hole should also impact American exceptionalism. The phrase in a market context refers to the continuing outperformance of US assets, aided by a strong dollar and by the magnetic effect of the big tech groups that currently dominate the world. The reaction to the Liberation Day tariffs suggested exceptionalism might be over, and trust in US institutions fatally compromised. Now we're in a gray area: the tariffs are in force at much the same levels outlined then (except in China), and the world is living with it. The dollar is at a fascinating juncture. Foreign exchange traders care about trends. The DXY dollar index's fall ended earlier this year exactly when it hit an upward trend line that started with the low in 2011 before the euro-zone crisis powered the dollar higher. This resistance point, notes Brigden, offers a natural opportunity for traders to halt and decide whether they are prepared to take the dollar lower: The bearish dollar hypothesis revolves around capital flows. As countries repatriate money, the huge allocations that foreign fund managers hold in US equities will require flows out of the dollar. The Magnificent Seven stocks attract foreign money; exclude them, and the remaining US large caps are now significantly lagging the rest of the world. There's room for this trend to go much further: However, the actual flows in and out of US assets tell a different story. Equity flows went negative last year, but are back to strongly positive. Flows into Treasuries are diminishing, but still positive — it's not long since emerging market central banks drove outright outflows during the pandemic. Overall, flows into dollar-based assets are stronger than ever:  Source: Brookings Institution It's hard to square this with the narrative of a major crisis of confidence in the US. The dollar bears' last stand might conceivably come at Jackson Hole. Robin Brooks of the Brookings Institution argues: The most likely reason why these inflows haven't yet translated into a dollar rebound is that there are still way more Fed cuts priced than for other central banks, so there may still be lots of short-term outflows not covered in these data. If that's the case, I expect this tension to be resolved in favor of the dollar.

A hawkish surprise from Powell would also be a shock for those betting against the dollar. So, to a lesser extent, would a "hawkish cut" next month, in which the FOMC signaled it was unwilling to cut again in a hurry. If Powell wants to turn markets around, his chances look much better than Custer's. |

No comments