Buffett's butterfly turns into terror over Tokyo

Tokyo has started the week with a huge selloff.

This is a case of a butterfly flapping its wings in New York causing a typhoon in Japan, not the other way around.

Warren Buffett, by halving his Apple stake and moving to cash, will not help sentiment Monday morning.

When the US employment rate triggered the Sahm Rule, it also triggered the selloffs.

The Bank of Japan's rate hike starts to filter through.

AND the mighty migrating Monarch butterflies.

What Just Happened?

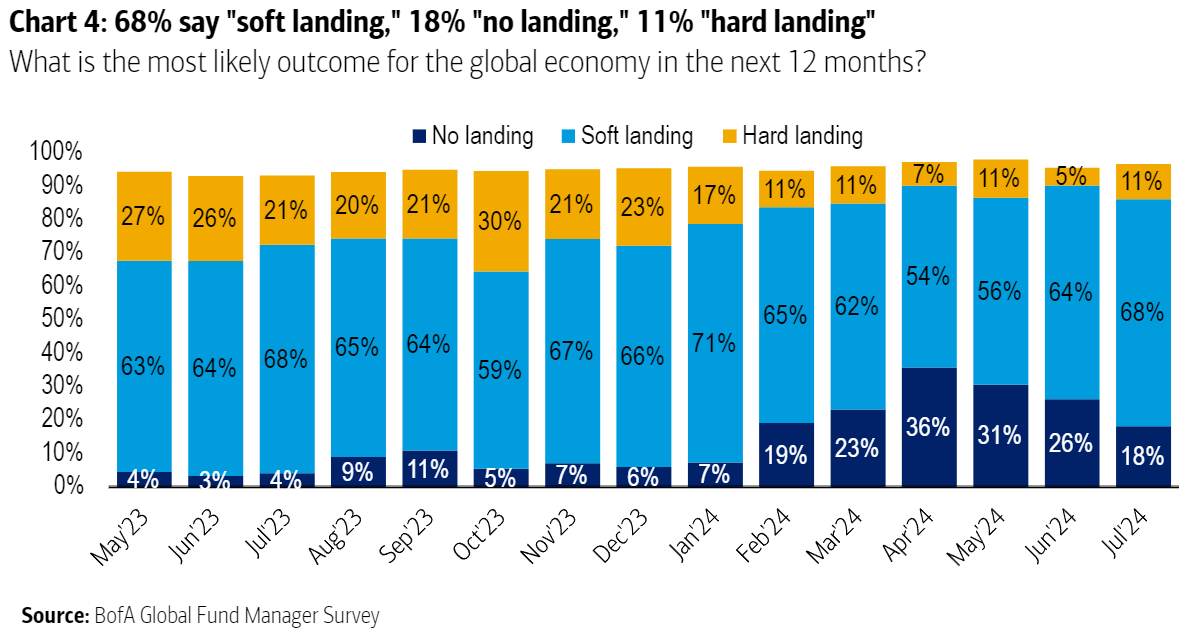

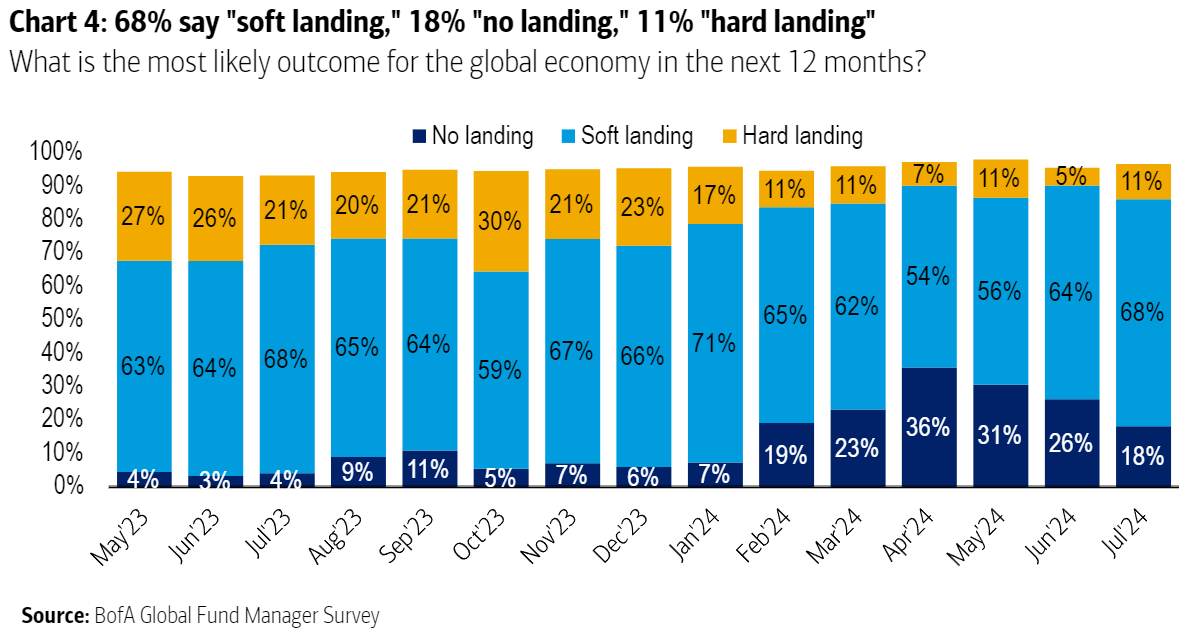

Tokyo markets have opened the week with great drama and it's best to think of it as chaos theory at work. A butterfly flapping its wings in Wall Street (with some help from Warren Buffett, the Federal Reserve, and innumerable retail investors) has created a Tokyo typhoon (or morphed into a giant, markets destroying Mothra, if you're a fan of Japanese monster classics). To explain why, we must start with the expectations embedded before prices started to churn. The July survey of global fund managers produced by Bank of America Corp. showed high confidence in a soft landing for the global economy (expected by 68%). The chance of a hard landing was put at only 11%, although this did represent a rise from earlier in the year:

For financial assets, that confidence in a soft landing created the risk of a hard one for prices that now seems to be happening. While a lot was running on the notion that any slowdown would be a gentle one, the idea of an economic weakening was taking hold. The proportion expecting a strong US economy in the next 12 months dropped to a seven-month low:

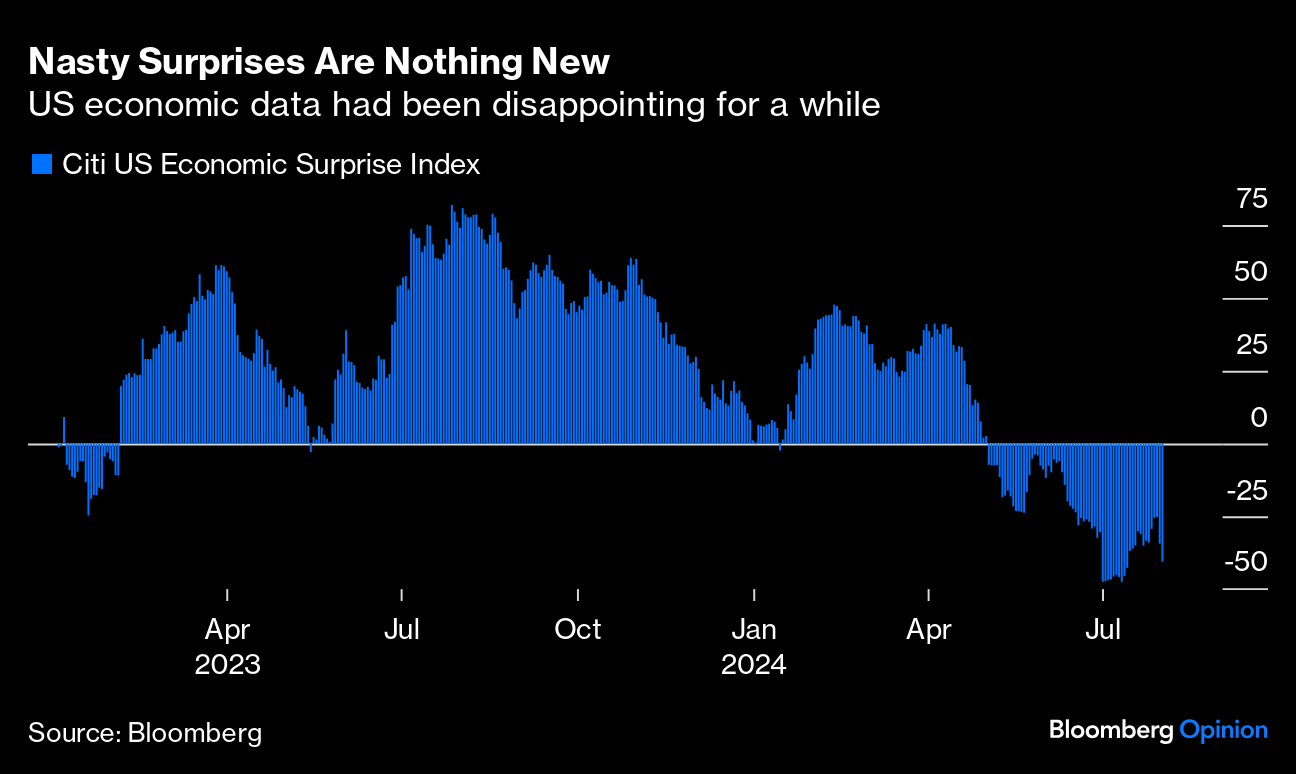

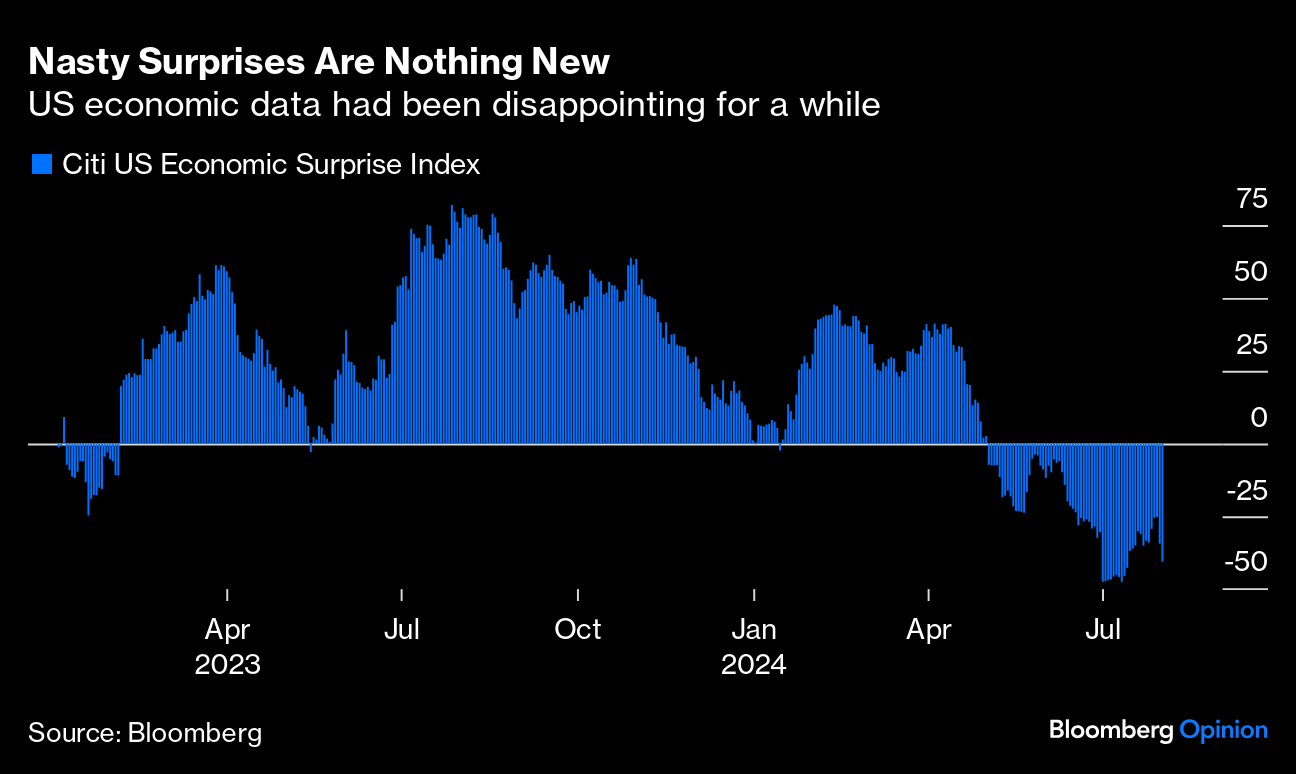

Meanwhile, US data have been disappointing prior expectations for a few months, a trend that reached its worst early in July. This is the widely followed economic surprise index, maintained by Citi:

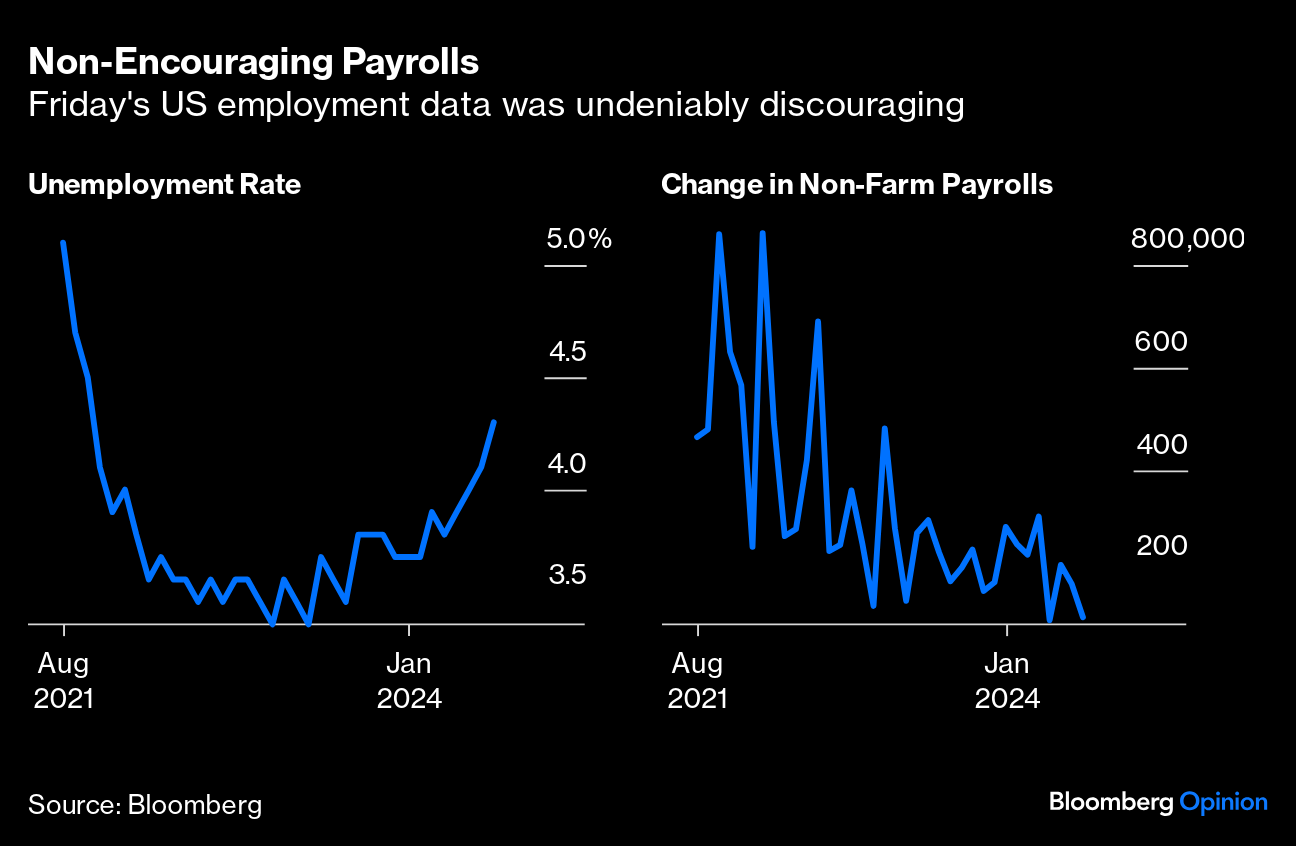

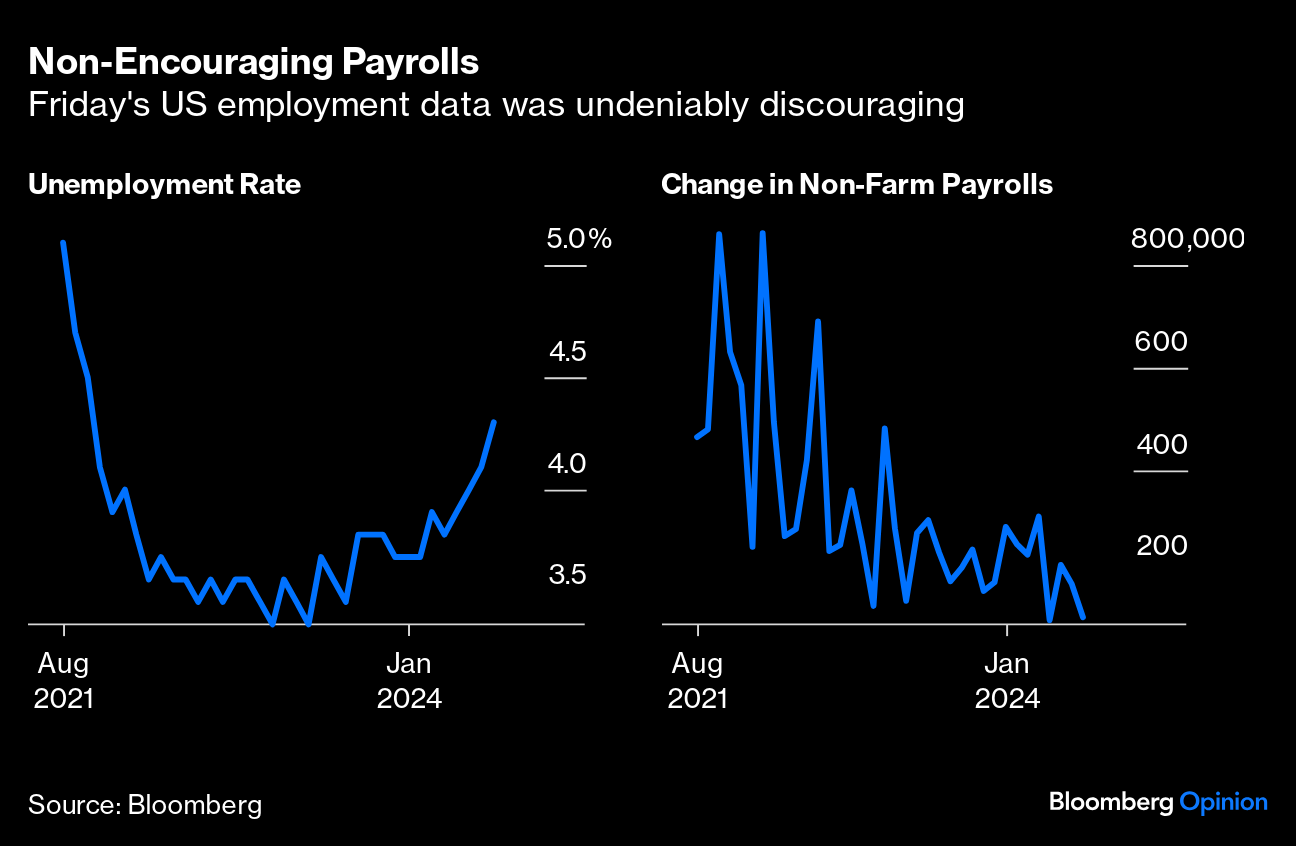

With investors conscious that the US economy was slowing, but still retaining their confidence, the latest employment numbers on hit. Non-farm payrolls grew by slightly more than 100,000, and the unemployment rate remains below 4.5% (having reached 10% after the Global Financial Crisis,, so the numbers scarcely screamed recession. But they disappointed, and came as negative surprises were intensifying. What might have been mediocre numbers in another context instead came over as terrible:

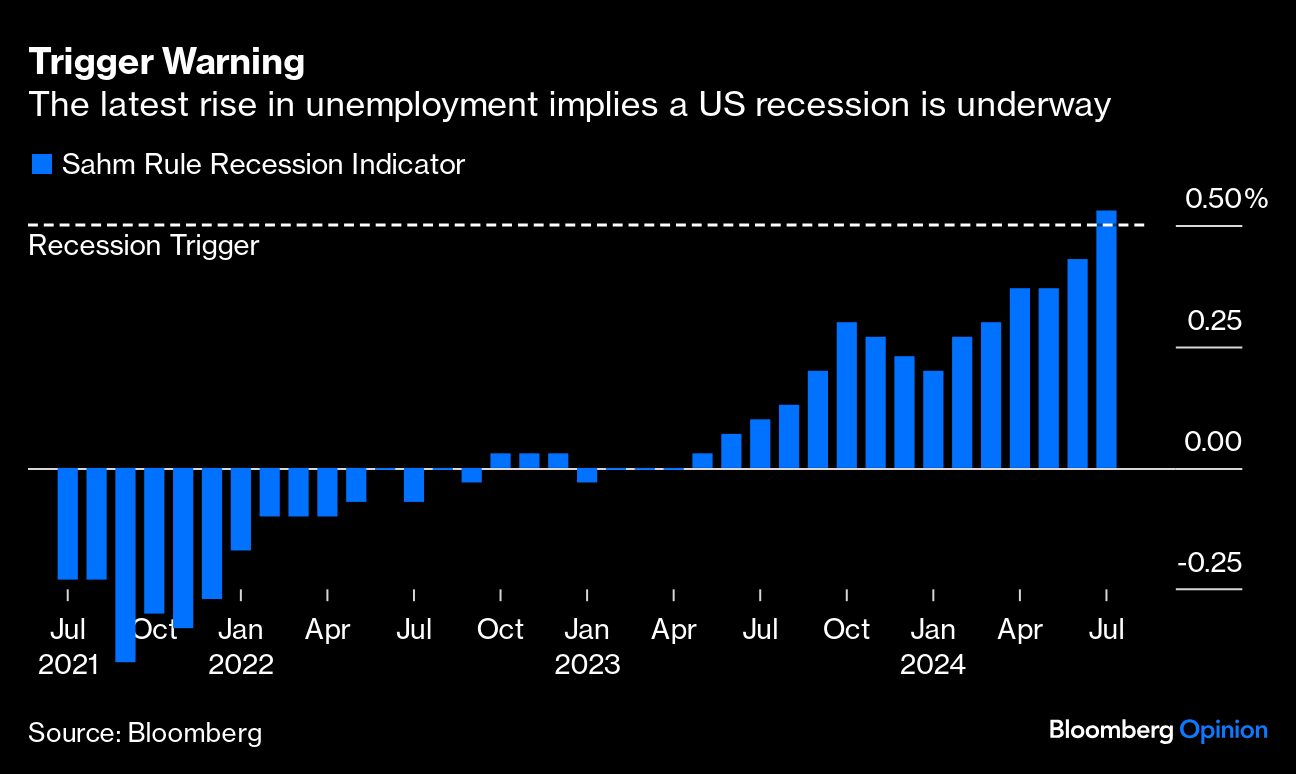

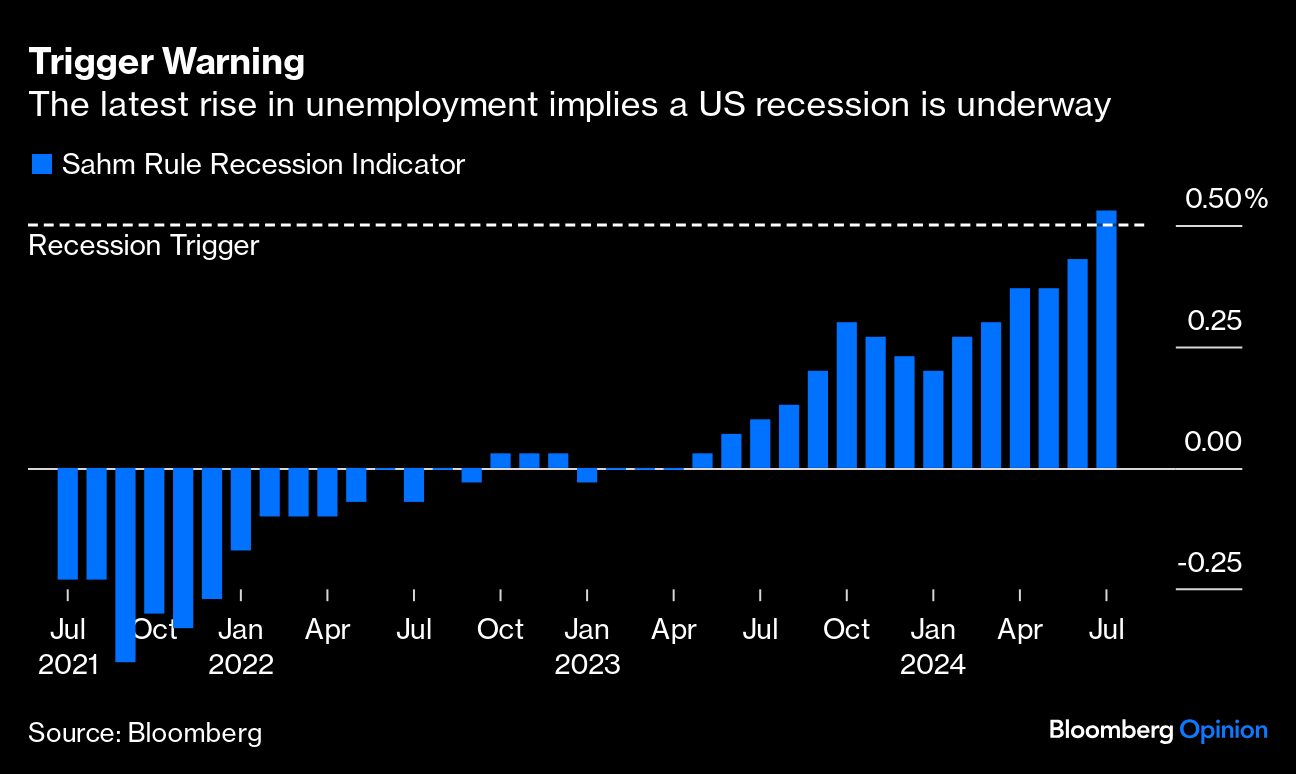

If there's one reason why the numbers were unwelcome, it's because the rise in the unemployment rate triggered the Sahm Rule (explained by Bloomberg Opinion colleague Claudia Sahm on Bloomberg TV):

Sahm herself is on record suggesting that in the bizarre post-pandemic conditions, it's possible that her rule — which is based on how fast the unemployment rate is increasing, even if from a low base — may give a false positive this time. Both the inverted yield curve in the bond market and the leading economic indicators compiled by the Conference Board, normally two close-to-foolproof recession indicators, have been screaming for a slowdown for the better part of two years. It still hasn't happened. But a new recession warning, just as the Federal Reserve decided to leave interest rates in place even as counterparts were cutting, drove serious alarm.

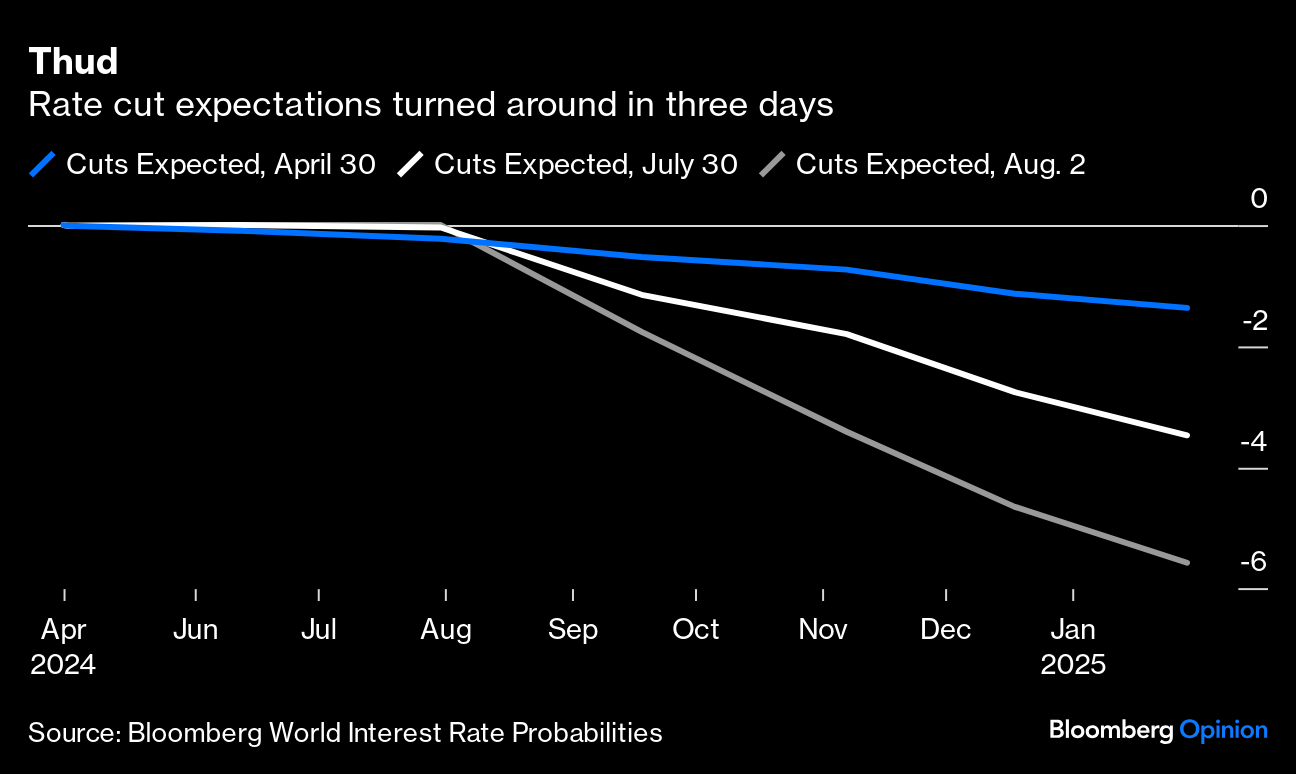

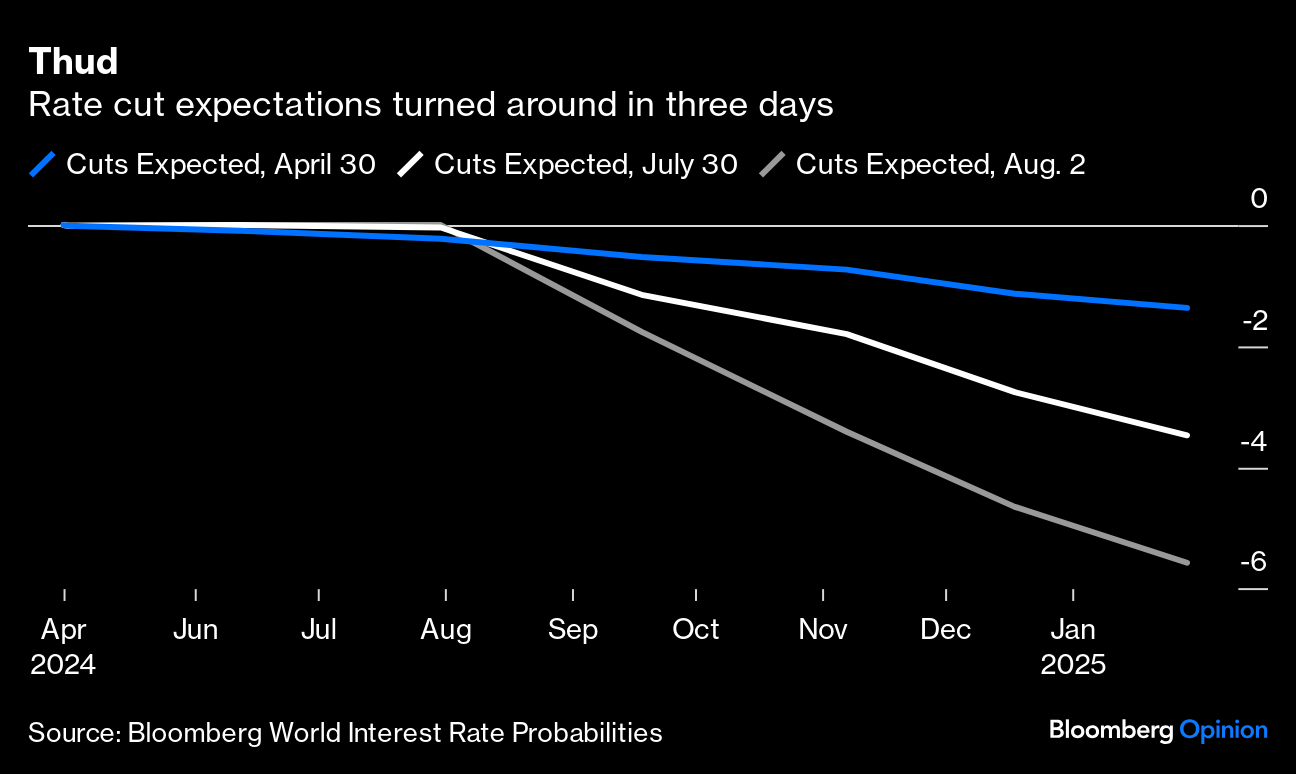

That alarm centers on the Fed. Traders always want lower rates. Sometimes, like now, they're desperate to avert something terrible. Over the last three months, expectations for cuts had steadily strengthened. Since Wednesday's Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the bottom has dropped out of fed funds futures. Over the next four meetings, they're pricing 1.5 percentage points of cuts, which implies that the central bank will cut by more than the standard 25 basis points at least twice:

Returning to the BofA survey, which showed 68% of asset allocators expected a soft landing, this can be viewed as a belated attempt to catch up with the real possibility of a harder one, both because the data is worsening and the Fed appears to be behind the curve. Their prior beliefs were reflected in a bullish allocation to stocks (a net 33% said they were overweight), while a net 9% were underweight bonds. Bonds beat stocks when people think a slowdown will force rate cuts, particularly when the market is positioned for the opposite. The turnaround shows up in different ways in different assets. This dashboard (compiled as of Friday's close, before Monday morning's Tokyo opening) summarizes what has happened to 2024's most successful trades:

Gold is now outpacing the US stock market, and industrial metals are down (suggesting alarm about a slowdown). A bet on stocks to beat bonds (expressed through the most popular exchange-traded funds, known for their tickers as SPY and TLT) has reversed spectacularly, although it is still ahead of a 60:40 trade (60% stocks and 40% bonds) for the year. Big caps have tumbled compared to small caps, although they recovered somewhat after Friday's unemployment data. The Magnificent Seven correction continues apace. Bitcoin is down almost 16% in the last five days, but it's still delivered like few other trades for the year so far.

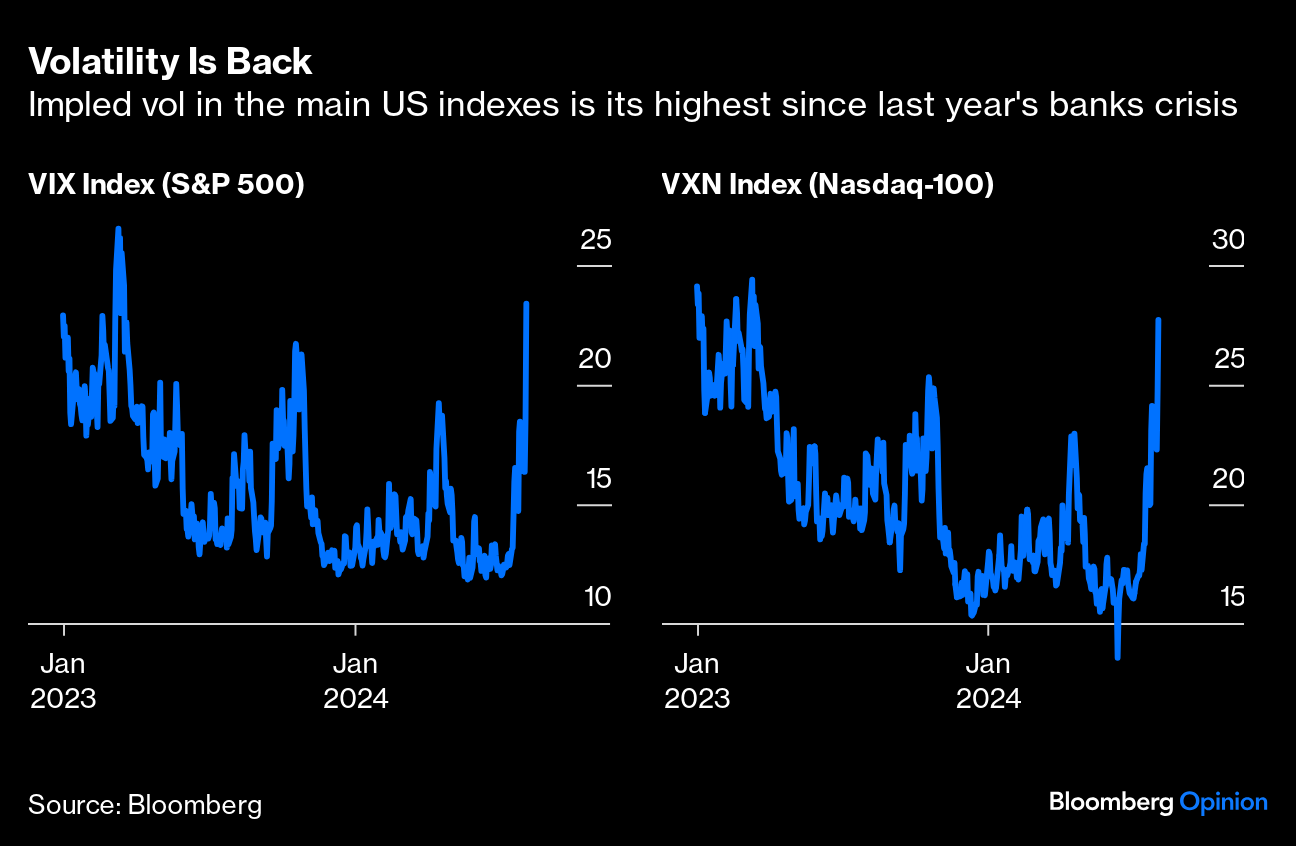

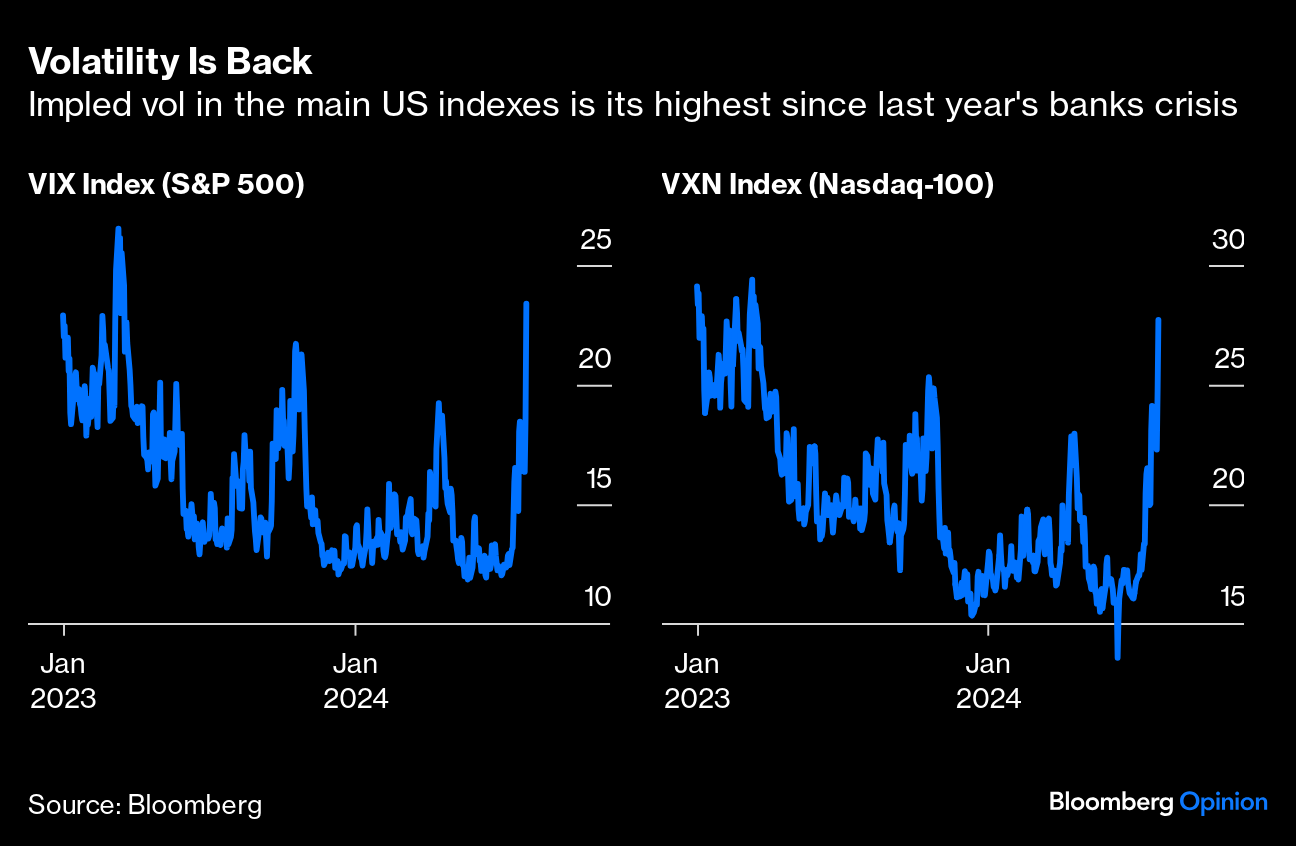

Stock market volatility is back, almost topping the levels reached during the regional banking crisis early last year. The alarming developments in Asia can be expected to amplify nerves:

The Fed will not want to admit an error, or risk causing panic, by cutting fed funds before its next scheduled meeting in September, so life looks likely to be tough for a while. It's worth making clear for now, however, that payrolls are still expanding, and the trades that have reversed in the last few days had generally looked well overdue for a correction. The concern should be whether such a sudden downdraft will create leveraged losses that could cause a cascade.

Monarch butterflies: next stop, Mexico? Photographer: Steve Russell/Toronto Star/Getty Images

On that note, the foreign exchange currency trade looks the most disquieting, with the popular tactic of borrowing in yen and parking in the Mexican peso suddenly down for the year. As carry trades are often leveraged, this might trigger worse to come. And that brings us to Tokyo, where market moves have now gone far beyond a simple correction.

Not Made Only in Japan

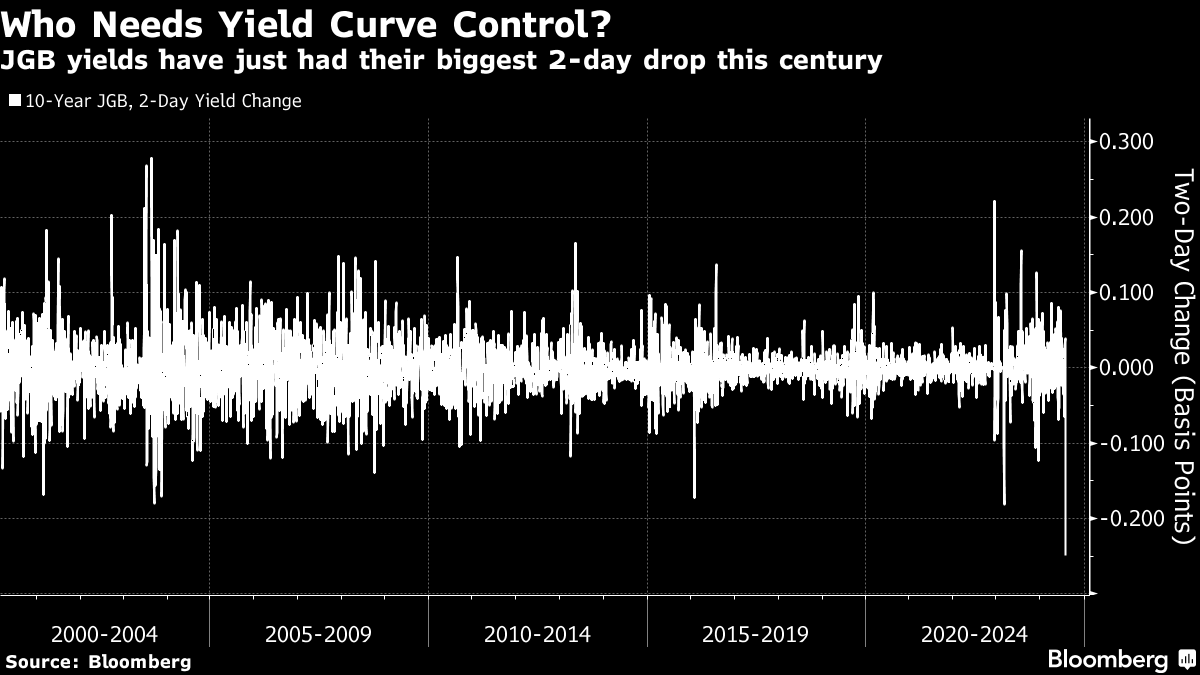

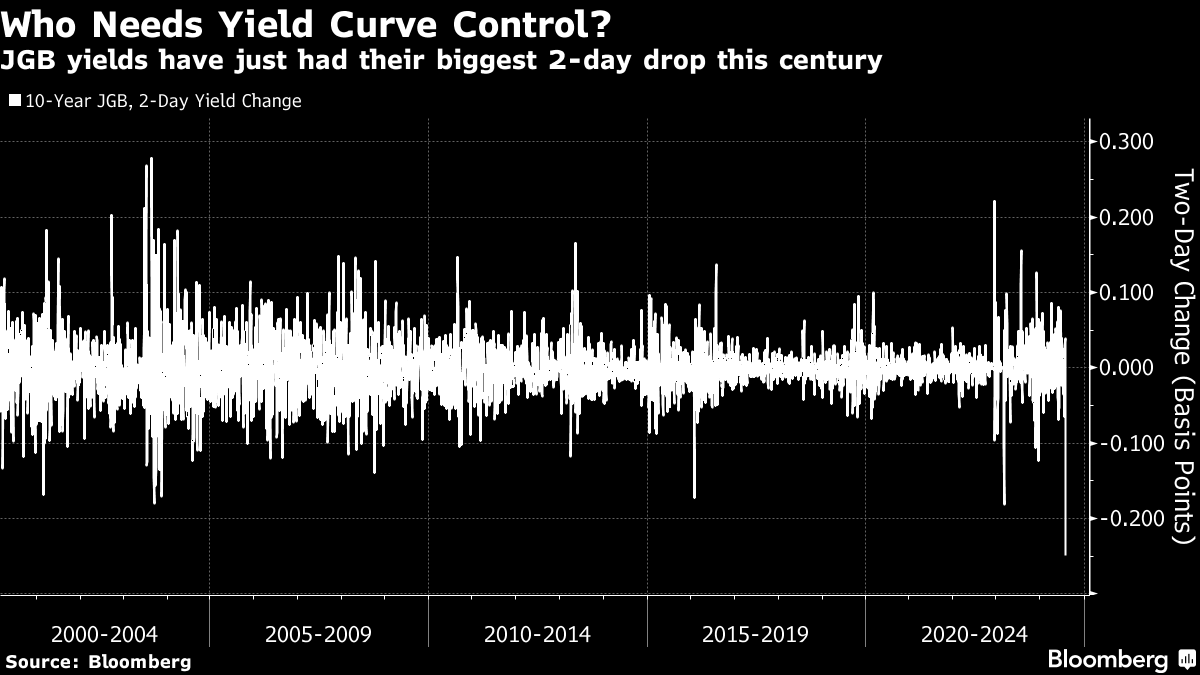

Friday brought quite a selloff in Tokyo. At the time of writing, Monday morning is delivering an extraordinary sequel. Only last week, the Bank of Japan announced that it would be halving its purchases of bonds. The discontinued policy of Yield Curve Control, which had latterly kept the 10-year JGB yield below 1%, was well and truly over. Yet since the market opened Friday, we've witnessed the biggest two-day fall in JGB yields this century:

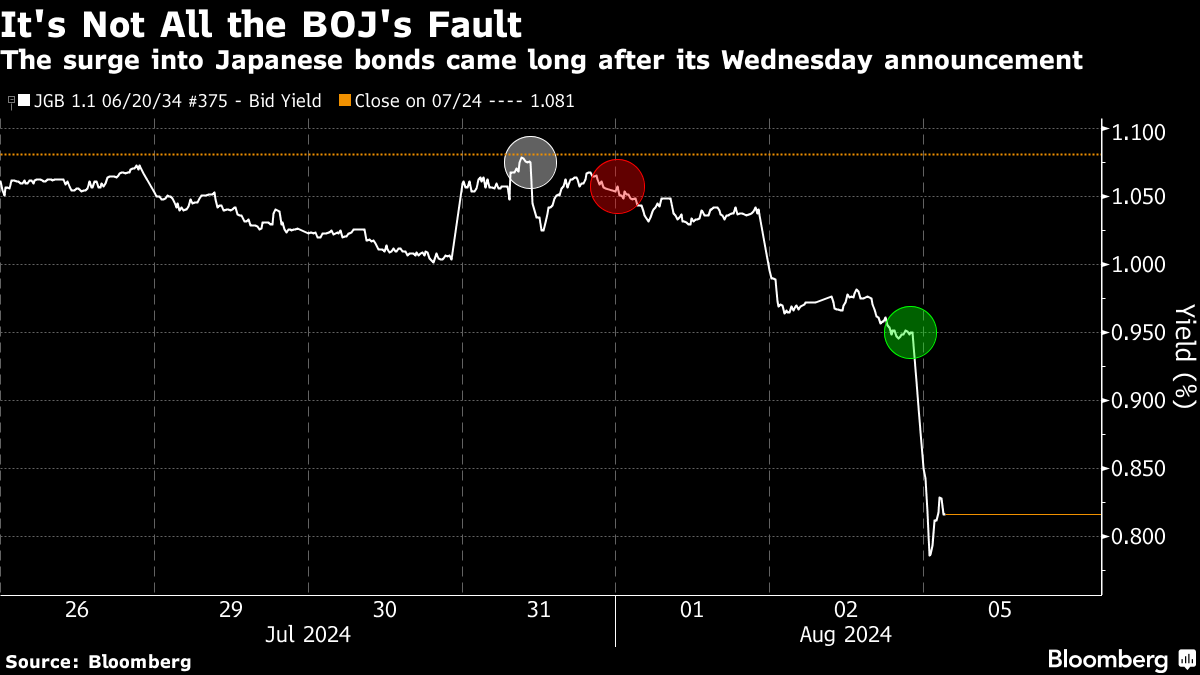

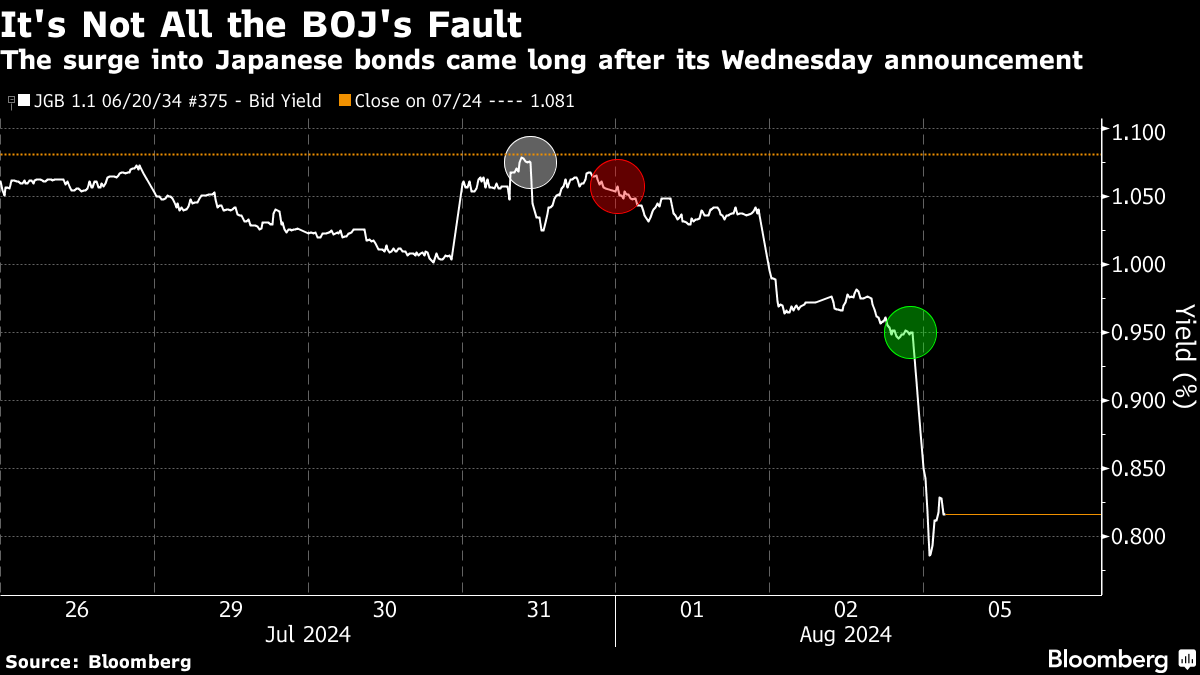

To demonstrate how this was sequenced, here is the 10-year JGB yield since the beginning of last week. The three rings are, in order, the BOJ meeting, the Japanese market's first opportunity to respond to the FOMC meeting, and the first chance to respond to the US unemployment data. This doesn't mean that the BOJ didn't contribute to the accident, but it does mean that other forces were at work:

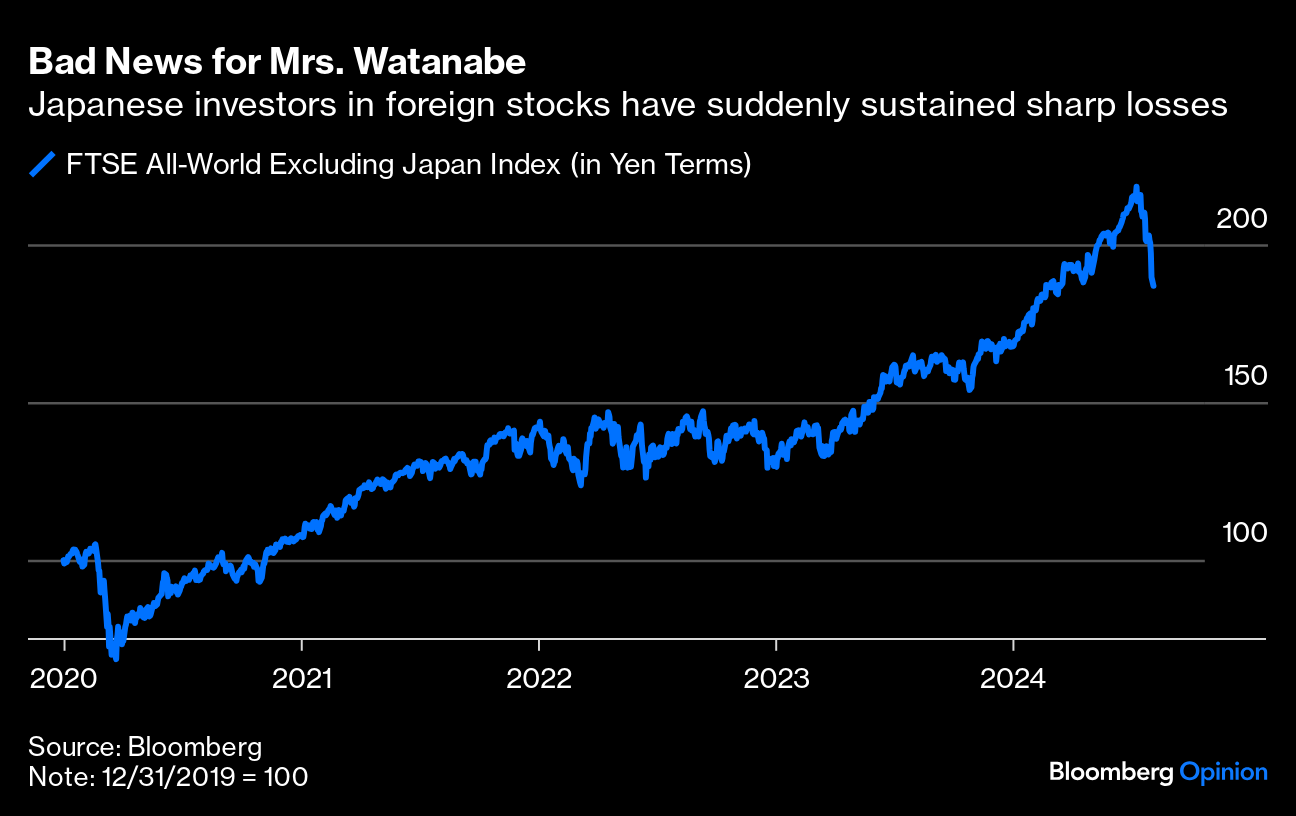

What were those other forces? Japanese investors love putting their money to work overseas. Combine the extraordinary performance of the US stock market with a historically weakening yen, and the result for Japanese investors is fantastic, even if it does mean that Japanese companies go without needed capital. (One frustrated investment banker complained to me that at Tokyo roadshows, people ask if it's time to buy Tesla, not Mitsubishi). This is how FTSE's index for the world outside Japan has performed in yen terms since the eve of the pandemic:

Meanwhile, foreign investors also like borrowing in yen and parking elsewhere via the carry trade. Like Mrs. Watanabe, the mythical Japanese retail investor, these people will be burned, and their actions as they try to minimize the pain could make the situation worse. By liquidating their foreign holdings and bringing money home, they drive the yen up further. Put all of this together, and at the time of writing, the Nikkei 225 stock index has opened down 7% meaning that it has shed 20%, the typical definition for a bear market, in barely three weeks. If there was any reason why the Japanese stock market suddenly cracked Friday morning, it's that the yen had dropped below the psychological barrier of 150 to the dollar.

Dislocations this big are dangerous. When someone takes a big leveraged loss, others must make forced sales in turn. What is happening in Japanese markets now is more to do with events beyond its borders. Norihiro Yamaguchi of Oxford Economics said:

The sudden reversal in yen, driven both by a drop in US yields and the BOJ's hawkish stance prevailing in its July meeting, is another idiosyncratic factor for Japanese equity. Though domestic fundamentals haven't changed a lot since a few weeks ago, Japan's equity market is unlikely to reverse at least till the US market calms.

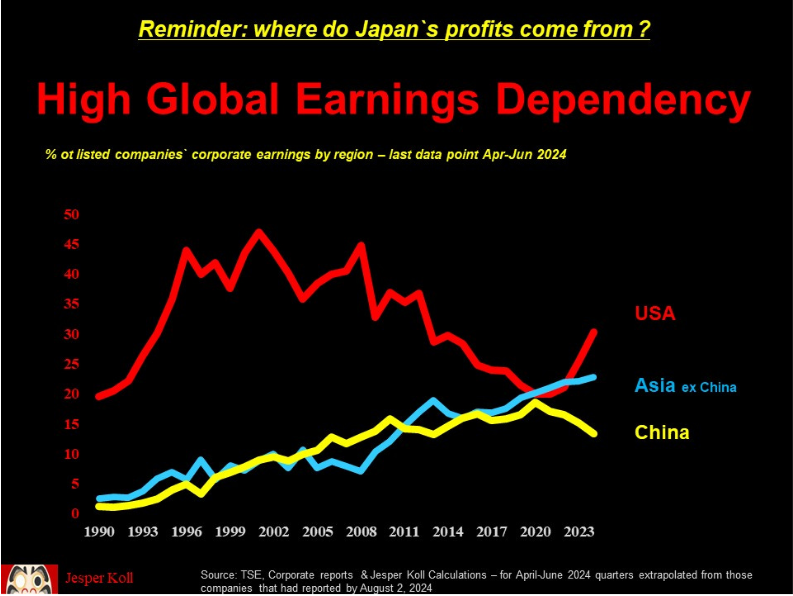

Jesper Koll, the veteran analyst who runs the Japan Optimist newsletter, shows that the country is dependent on the US in economic as well as financial terms. It's become a vital market for Japanese exports:

"In global financial markets, all starts and ends with America: As US recession risks rise, the US dollar up-cycle comes to end," Koll says. "Don't fight it. Warren Buffet has just raised his cash holdings to an all-time high he expects to be able to buy cheaper in the future. Japan investors will follow his lead."

The actions of Japan's investors taking cover from the monstrous US moth above them could cause accidents elsewhere. For example, getting out of carry trades means selling Mexican pesos. Mexico's exchange rate with the currency of its huge northern neighbor is crucial to its economy. This is what's happening to it:

This is not a case of a butterfly flapping its wings in Tokyo and wreaking drama elsewhere. Rather, Japan is being hit by the waves caused by butterflies in New York and Washington. The risk of a major financial accident is evident. Stopping it will depend primarily on what happens next in the US.

Et tu, Warren?

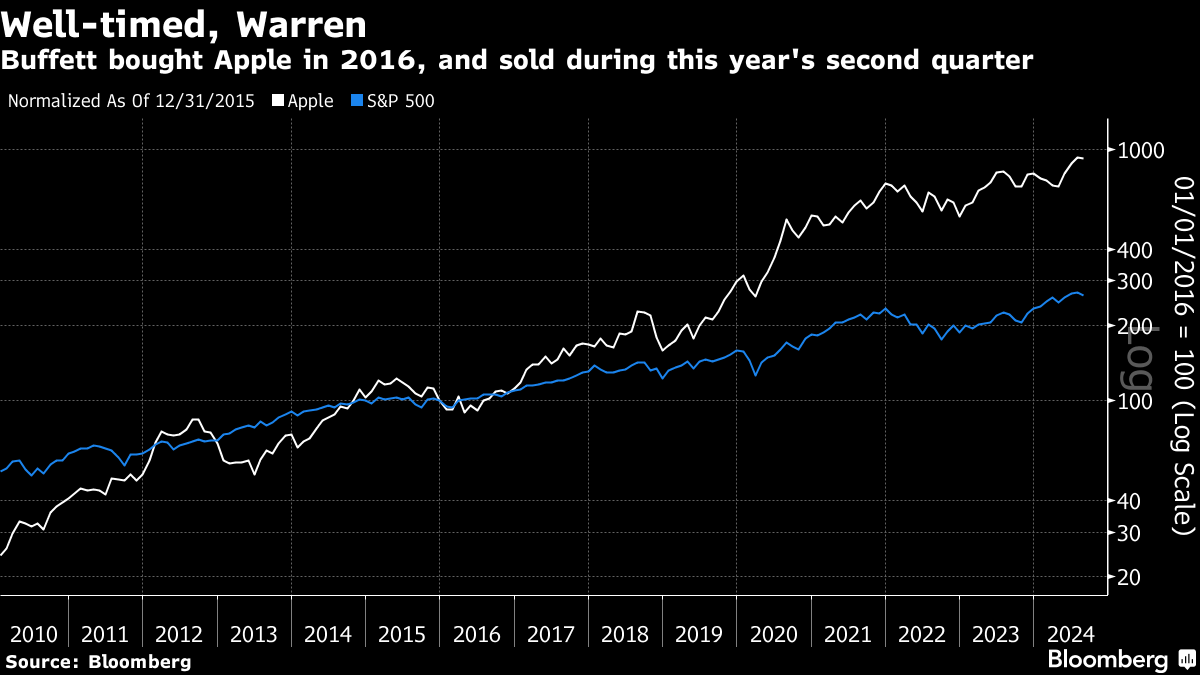

Many in my inbox seem to be rather annoyed with Warren Buffett. That's because of the weekend's news that Berkshire Hathaway Inc. sold about half its stake in Apple Inc. during the second quarter. It had entered the stock in 2016 and, as this terminal chart shows, the Buffett timing seems to have been as impeccable as ever. It's normalized to that both the S&P 500 and Apple are at 100 at the point when Berkshire bought:

Berkshire Hathaway is a big investor, and Buffett has many fans, but Berkshire's sale in itself shouldn't have significant knock-on effects. Buffett's decision to take (massive) profits in a trade that had come to dominate his portfolio, widely considered the most crowded in the market, shouldn't surprise anyone.

All that said, the sight of the world's most respected investor getting out of one of the Magnificent Seven and building a $276.9 billion cash pile for the buying opportunities he sees ahead is not good for rattled sentiment. Buffett shares in the responsibility for Tokyo's selloff. The next step is to see whether American retail investors keep their patience with Big Tech.

Warren Buffett rattles sentiment. Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

Survival Tips

Getting back to butterflies: the Monarch butterflies are soon setting out on their migration to nesting grounds in the forests of central Mexico, where they gather in such numbers that tree branches break under their weight. Watching them gather there, ideally in January or February, is an almost religious experience. If you ever have the chance, head to Michoacan to see them. Have a great week everyone.

This is a case of a butterfly flapping its wings in New York causing a typhoon in Japan, not the other way around.

Warren Buffett, by halving his Apple stake and moving to cash, will not help sentiment Monday morning.

When the US employment rate triggered the Sahm Rule, it also triggered the selloffs.

The Bank of Japan's rate hike starts to filter through.

AND the mighty migrating Monarch butterflies.

What Just Happened?

Tokyo markets have opened the week with great drama and it's best to think of it as chaos theory at work. A butterfly flapping its wings in Wall Street (with some help from Warren Buffett, the Federal Reserve, and innumerable retail investors) has created a Tokyo typhoon (or morphed into a giant, markets destroying Mothra, if you're a fan of Japanese monster classics). To explain why, we must start with the expectations embedded before prices started to churn. The July survey of global fund managers produced by Bank of America Corp. showed high confidence in a soft landing for the global economy (expected by 68%). The chance of a hard landing was put at only 11%, although this did represent a rise from earlier in the year:

For financial assets, that confidence in a soft landing created the risk of a hard one for prices that now seems to be happening. While a lot was running on the notion that any slowdown would be a gentle one, the idea of an economic weakening was taking hold. The proportion expecting a strong US economy in the next 12 months dropped to a seven-month low:

Meanwhile, US data have been disappointing prior expectations for a few months, a trend that reached its worst early in July. This is the widely followed economic surprise index, maintained by Citi:

With investors conscious that the US economy was slowing, but still retaining their confidence, the latest employment numbers on hit. Non-farm payrolls grew by slightly more than 100,000, and the unemployment rate remains below 4.5% (having reached 10% after the Global Financial Crisis,, so the numbers scarcely screamed recession. But they disappointed, and came as negative surprises were intensifying. What might have been mediocre numbers in another context instead came over as terrible:

If there's one reason why the numbers were unwelcome, it's because the rise in the unemployment rate triggered the Sahm Rule (explained by Bloomberg Opinion colleague Claudia Sahm on Bloomberg TV):

Sahm herself is on record suggesting that in the bizarre post-pandemic conditions, it's possible that her rule — which is based on how fast the unemployment rate is increasing, even if from a low base — may give a false positive this time. Both the inverted yield curve in the bond market and the leading economic indicators compiled by the Conference Board, normally two close-to-foolproof recession indicators, have been screaming for a slowdown for the better part of two years. It still hasn't happened. But a new recession warning, just as the Federal Reserve decided to leave interest rates in place even as counterparts were cutting, drove serious alarm.

That alarm centers on the Fed. Traders always want lower rates. Sometimes, like now, they're desperate to avert something terrible. Over the last three months, expectations for cuts had steadily strengthened. Since Wednesday's Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the bottom has dropped out of fed funds futures. Over the next four meetings, they're pricing 1.5 percentage points of cuts, which implies that the central bank will cut by more than the standard 25 basis points at least twice:

Returning to the BofA survey, which showed 68% of asset allocators expected a soft landing, this can be viewed as a belated attempt to catch up with the real possibility of a harder one, both because the data is worsening and the Fed appears to be behind the curve. Their prior beliefs were reflected in a bullish allocation to stocks (a net 33% said they were overweight), while a net 9% were underweight bonds. Bonds beat stocks when people think a slowdown will force rate cuts, particularly when the market is positioned for the opposite. The turnaround shows up in different ways in different assets. This dashboard (compiled as of Friday's close, before Monday morning's Tokyo opening) summarizes what has happened to 2024's most successful trades:

Gold is now outpacing the US stock market, and industrial metals are down (suggesting alarm about a slowdown). A bet on stocks to beat bonds (expressed through the most popular exchange-traded funds, known for their tickers as SPY and TLT) has reversed spectacularly, although it is still ahead of a 60:40 trade (60% stocks and 40% bonds) for the year. Big caps have tumbled compared to small caps, although they recovered somewhat after Friday's unemployment data. The Magnificent Seven correction continues apace. Bitcoin is down almost 16% in the last five days, but it's still delivered like few other trades for the year so far.

Stock market volatility is back, almost topping the levels reached during the regional banking crisis early last year. The alarming developments in Asia can be expected to amplify nerves:

The Fed will not want to admit an error, or risk causing panic, by cutting fed funds before its next scheduled meeting in September, so life looks likely to be tough for a while. It's worth making clear for now, however, that payrolls are still expanding, and the trades that have reversed in the last few days had generally looked well overdue for a correction. The concern should be whether such a sudden downdraft will create leveraged losses that could cause a cascade.

Monarch butterflies: next stop, Mexico? Photographer: Steve Russell/Toronto Star/Getty Images

On that note, the foreign exchange currency trade looks the most disquieting, with the popular tactic of borrowing in yen and parking in the Mexican peso suddenly down for the year. As carry trades are often leveraged, this might trigger worse to come. And that brings us to Tokyo, where market moves have now gone far beyond a simple correction.

Not Made Only in Japan

Friday brought quite a selloff in Tokyo. At the time of writing, Monday morning is delivering an extraordinary sequel. Only last week, the Bank of Japan announced that it would be halving its purchases of bonds. The discontinued policy of Yield Curve Control, which had latterly kept the 10-year JGB yield below 1%, was well and truly over. Yet since the market opened Friday, we've witnessed the biggest two-day fall in JGB yields this century:

To demonstrate how this was sequenced, here is the 10-year JGB yield since the beginning of last week. The three rings are, in order, the BOJ meeting, the Japanese market's first opportunity to respond to the FOMC meeting, and the first chance to respond to the US unemployment data. This doesn't mean that the BOJ didn't contribute to the accident, but it does mean that other forces were at work:

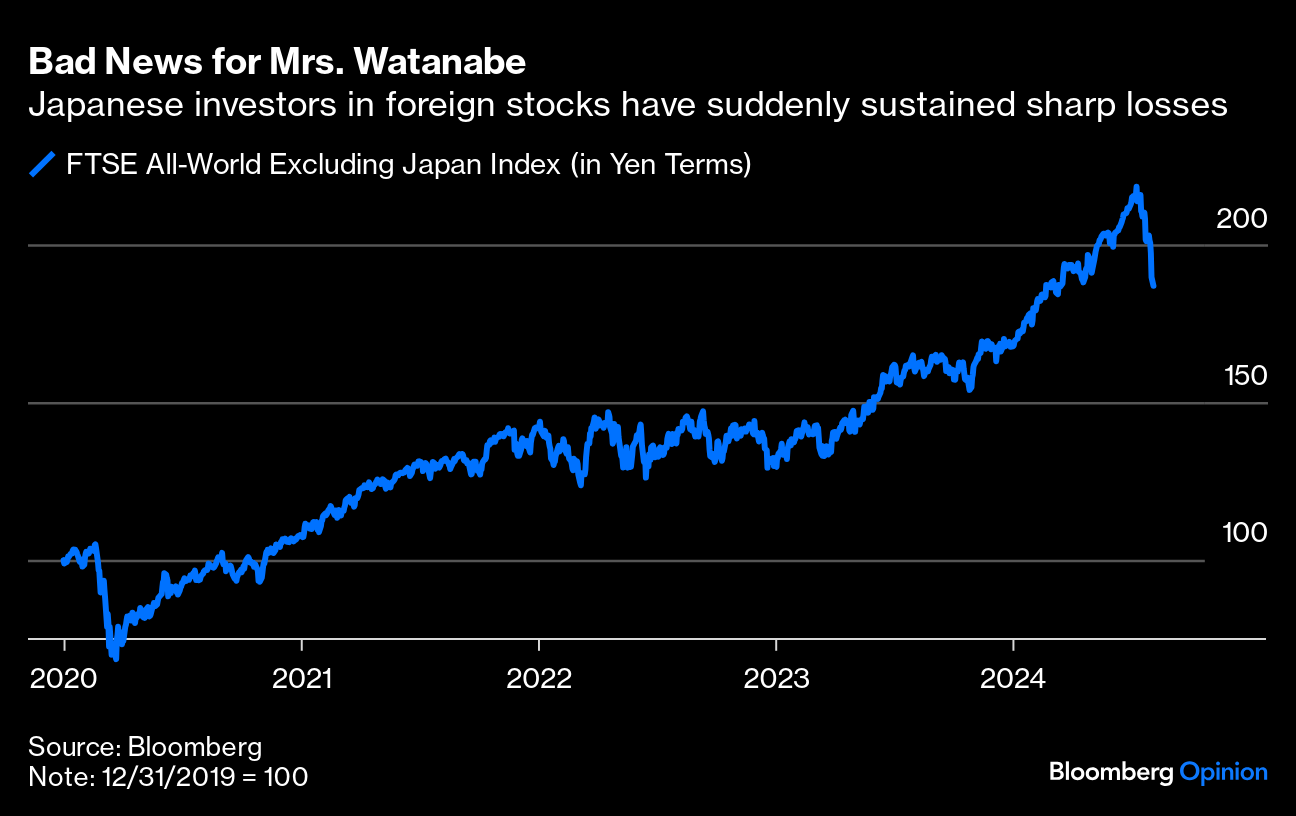

What were those other forces? Japanese investors love putting their money to work overseas. Combine the extraordinary performance of the US stock market with a historically weakening yen, and the result for Japanese investors is fantastic, even if it does mean that Japanese companies go without needed capital. (One frustrated investment banker complained to me that at Tokyo roadshows, people ask if it's time to buy Tesla, not Mitsubishi). This is how FTSE's index for the world outside Japan has performed in yen terms since the eve of the pandemic:

Meanwhile, foreign investors also like borrowing in yen and parking elsewhere via the carry trade. Like Mrs. Watanabe, the mythical Japanese retail investor, these people will be burned, and their actions as they try to minimize the pain could make the situation worse. By liquidating their foreign holdings and bringing money home, they drive the yen up further. Put all of this together, and at the time of writing, the Nikkei 225 stock index has opened down 7% meaning that it has shed 20%, the typical definition for a bear market, in barely three weeks. If there was any reason why the Japanese stock market suddenly cracked Friday morning, it's that the yen had dropped below the psychological barrier of 150 to the dollar.

Dislocations this big are dangerous. When someone takes a big leveraged loss, others must make forced sales in turn. What is happening in Japanese markets now is more to do with events beyond its borders. Norihiro Yamaguchi of Oxford Economics said:

The sudden reversal in yen, driven both by a drop in US yields and the BOJ's hawkish stance prevailing in its July meeting, is another idiosyncratic factor for Japanese equity. Though domestic fundamentals haven't changed a lot since a few weeks ago, Japan's equity market is unlikely to reverse at least till the US market calms.

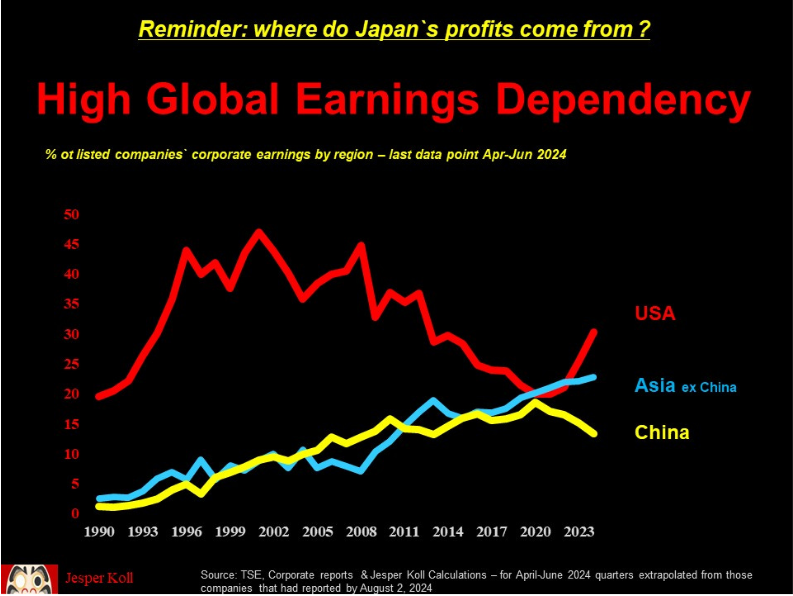

Jesper Koll, the veteran analyst who runs the Japan Optimist newsletter, shows that the country is dependent on the US in economic as well as financial terms. It's become a vital market for Japanese exports:

"In global financial markets, all starts and ends with America: As US recession risks rise, the US dollar up-cycle comes to end," Koll says. "Don't fight it. Warren Buffet has just raised his cash holdings to an all-time high he expects to be able to buy cheaper in the future. Japan investors will follow his lead."

The actions of Japan's investors taking cover from the monstrous US moth above them could cause accidents elsewhere. For example, getting out of carry trades means selling Mexican pesos. Mexico's exchange rate with the currency of its huge northern neighbor is crucial to its economy. This is what's happening to it:

This is not a case of a butterfly flapping its wings in Tokyo and wreaking drama elsewhere. Rather, Japan is being hit by the waves caused by butterflies in New York and Washington. The risk of a major financial accident is evident. Stopping it will depend primarily on what happens next in the US.

Et tu, Warren?

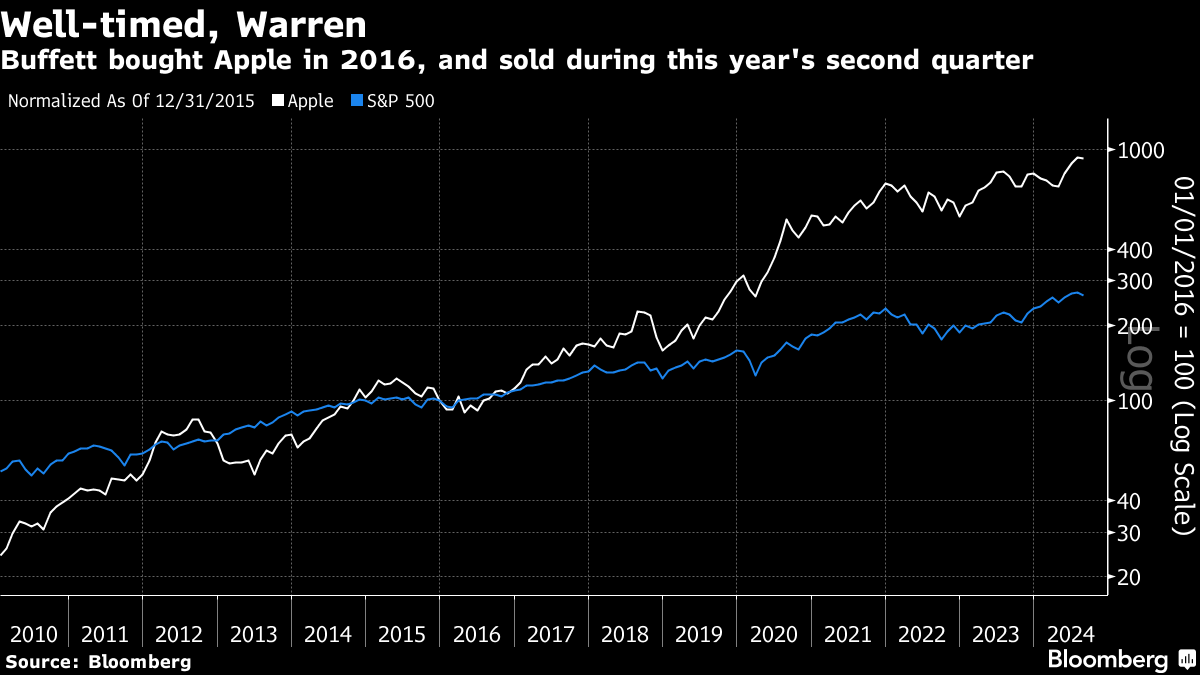

Many in my inbox seem to be rather annoyed with Warren Buffett. That's because of the weekend's news that Berkshire Hathaway Inc. sold about half its stake in Apple Inc. during the second quarter. It had entered the stock in 2016 and, as this terminal chart shows, the Buffett timing seems to have been as impeccable as ever. It's normalized to that both the S&P 500 and Apple are at 100 at the point when Berkshire bought:

Berkshire Hathaway is a big investor, and Buffett has many fans, but Berkshire's sale in itself shouldn't have significant knock-on effects. Buffett's decision to take (massive) profits in a trade that had come to dominate his portfolio, widely considered the most crowded in the market, shouldn't surprise anyone.

All that said, the sight of the world's most respected investor getting out of one of the Magnificent Seven and building a $276.9 billion cash pile for the buying opportunities he sees ahead is not good for rattled sentiment. Buffett shares in the responsibility for Tokyo's selloff. The next step is to see whether American retail investors keep their patience with Big Tech.

Warren Buffett rattles sentiment. Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

Survival Tips

Getting back to butterflies: the Monarch butterflies are soon setting out on their migration to nesting grounds in the forests of central Mexico, where they gather in such numbers that tree branches break under their weight. Watching them gather there, ideally in January or February, is an almost religious experience. If you ever have the chance, head to Michoacan to see them. Have a great week everyone.

No comments