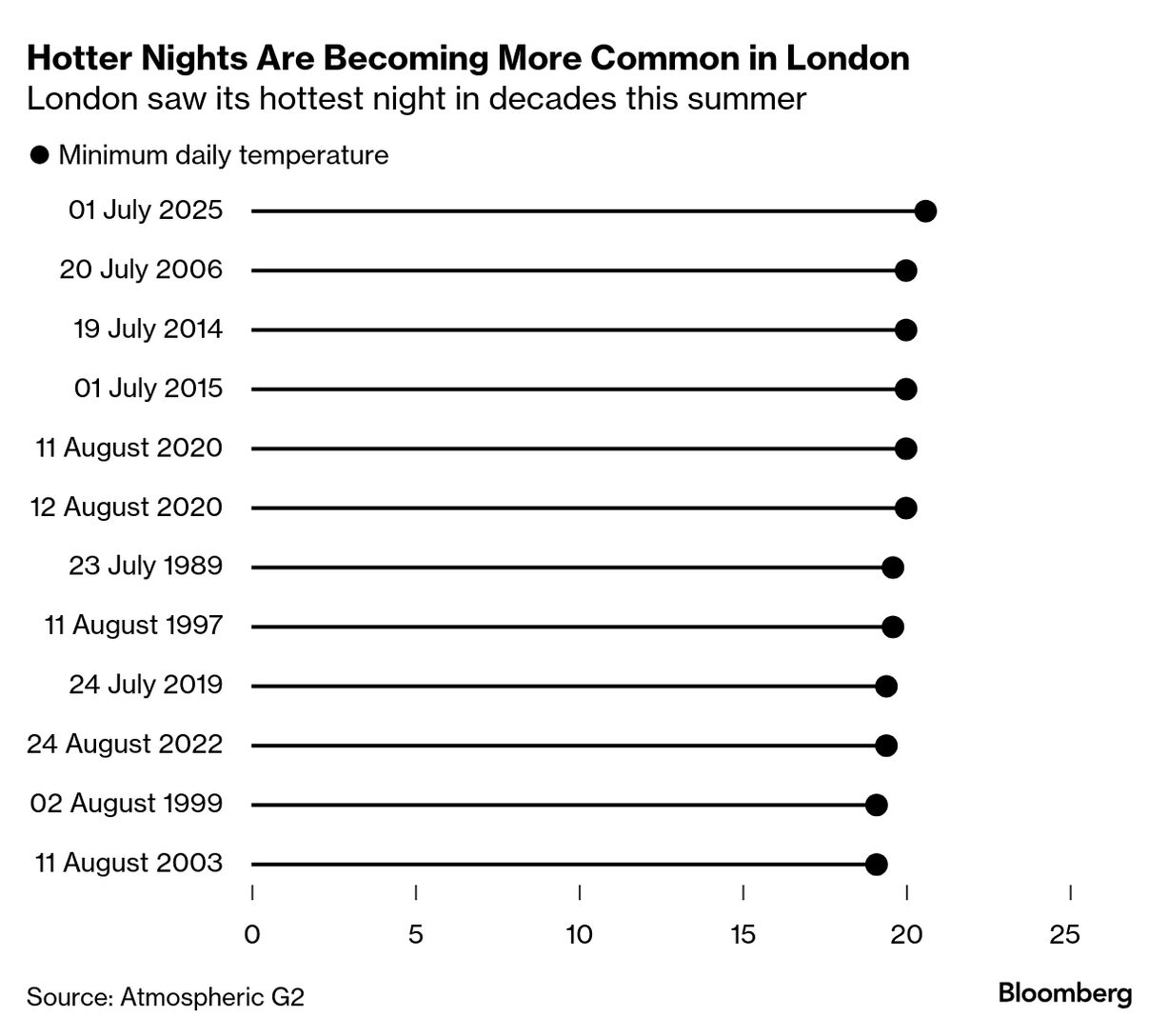

| By Olivia Rudgard In London, money can buy you many things – a $1,000 hotel room, an apartment overlooking Buckingham Palace, a £100-per-kilo steak – but not necessarily an air conditioner. That's something the city's wealthy residents are finding as they increasingly seek climate-control in their homes. AC units used to be an infrequent request, says Richard Gill, director at the London-based architecture firm Paul Archer Design. But nowadays roughly 30% of his clients, who are largely from London's higher earners, including lawyers and finance professionals, want air conditioning. Not all of them are getting it. Like those in many Northern Hemisphere cities, London's homes, whether they be a Victorian mansion or shiny newbuild apartment, are not well adapted to climate change. Hotter summers, including the UK's first 40C (104F) day in 2022, make homes with big south-facing windows, poor ventilation and little shading increasingly uncomfortable to live in. Hotter nights are a particular risk, and older people and young children in particular risk heat stress and long-term health problems if they are repeatedly losing sleep and unable to escape days of hot temperatures.  As I found in my story published today, for Londoners, obstacles to getting AC units installed in their homes vary. There can be technical or aesthetic restrictions on attaching units to old buildings. Apartment-dwellers face an extra layer of bureaucracy through having to ask for permission from their building's owner. And sometimes, councils simply reject claims of overheating. One of Gill's clients, who was living in a 1920s home in Highgate, north London, had sought permission to install air conditioning back in 2022. The council blocked the request because it judged that the house wouldn't overheat. The client "would beg to differ," Gill said. "Plenty of my clients go, 'I understand Richard, it is a first world problem, but my kids can't sleep and I work long hours.'" A quick scan of the websites of various London councils, which publish planning applications and decisions, show that Gill's clients aren't alone. Londoners have to show that their planned air conditioning unit isn't too noisy, won't look too ugly, and that there isn't anything else that could be done to keep their home cool without the power demand that an air conditioner adds to the grid. Restrictions prevent or delay installations in 30% to 40% of residential dwellings, according to the north London company Airconco. Some restrictions on installing AC units are slowly being relaxed. For example, the UK government this year added air-to-air heat pumps — air conditioning units that can both heat and cool — to a list of building work that can be done without asking for permission. And the government is considering adding air-to-air systems to a subsidy program designed to make heat pumps more accessible, in the interest of helping Britain reach its net zero goals. But the restrictions on protected buildings and for apartments will largely remain. Demand for air conditioning is on the rise across Europe. "We are used to having the heating mindset," says Simon Pezzutto, a senior researcher at the research center Eurac. "But now with climate change, we need to switch to the cooling mindset — and most cities in northern Europe are not prepared for that." Read the full story on Bloomberg.com. |

No comments