Algorithmic stablestretch | A fixed-rate bond has interest-rate risk. If you buy a five-year $100 bond that pays interest of 8%, and then interest rates go up by one percentage point, your bond is only worth $96. As rates go up, the yield of your bond has to go up, and to make the yield go up the price has to drop. A floating-rate bond has, to a first approximation, no interest-rate risk. If you buy a five-year $100 bond that pays interest of SOFR (the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, a standard interest benchmark) plus 4%, then today it pays 8.28% interest (SOFR is 4.28%); if SOFR goes up by one percentage point, then the bond pays 9.28% and it's probably still worth about $100. As rates go up, the yield of your bond goes up (it pays more interest), so the price doesn't have to drop. But that's not entirely right: A floating-rate bond normally floats with some index of prevailing risk-free-ish interest rates, like SOFR. But most companies that issue floating-rate bonds are not themselves risk-free. If a company issues a bond with a rate of SOFR plus 4% — if it issues at a credit spread of 400 basis points over the risk-free rate — then that means that the market thinks it is 400 basis points riskier than risk-free. If circumstances change — if the company gets riskier — then the right interest rate for that company will go up, even if prevailing risk-free rates don't. If SOFR stays the same, but the company's credit risk increases, then the yield of the bond will have to go up, and to make the yield go up the price has to drop. That is, floating-rate bonds don't have much interest-rate risk, but they do have credit risk. You might find this a bit untidy. You might want a bond that pays a floating rate that is not tied to prevailing interest rates, not "SOFR plus 4%" or whatever, but rather one that pays a floating rate that is like "whatever the right rate is each quarter to make the bond worth $100." That is, you want the bond's interest rate to float with both prevailing interest rates and the issuer's credit spread, or rather to float with the combination of them. I'm not exactly sure why you would want this. There's a fairly straightforward substitute, which is short-term debt: If a company borrows money for a month, and then next month it pays back the debt by borrowing new money for another month, then its borrowing costs will float with the market rate (each month it has to borrow at whatever rate the market demands). But I suppose that's kind of a pain — you have to do a whole new deal every month — and it might be tidier to have long-term debt with an interest rate that moves like short-term debt. There are not a lot of bonds like that, though, [1] for two reasons: - It is mechanically complicated: How do you set, each month, a rate that will make the bond trade at $100?

- It is quite wrong-way, for the issuer. If a company sells a bond whose rate floats with its own credit, then as its credit gets worse, it has to pay more interest. Why would it want that? For the issuer, that bond is essentially very-short term financing; it needs to be repriced every month. If the company's credit gets really bad, it might have to pay 30% or 40% interest on that bond. If it gets even worse, there might be no rate it can pay to keep the bond priced at $100.

The first problem is more or less solvable. One very partial solution, found in many syndicated loans, is to have some matrix of spreads based on financial metrics and/or credit ratings: "This loan pays interest of SOFR + 200, if the company is rated BBB- or better, or SOFR + 225, if it's rated BB+," etc. A more rigorous solution used to exist in the form of auction-rate securities (ARS), long-term bonds whose rates floated based on periodic auctions. (Brokers would put in bids saying "we will buy this bond at $100 with a rate of ____%," and whatever rate cleared the auction would be the new rate on the security.) This extremely did not solve the second problem, though: In 2008, as the market became very risk-averse, these auctions failed to find clearing prices, and the ARS market more or less died. MicroStrategy Inc. (now doing business as Strategy), the great financial innovator of our age, has delightfully solved both problems in the simplest possible way. This week it announced an offering of "Stretch" preferred stock ("Variable Rate Series A Perpetual Stretch Preferred Stock," ticker STRC) whose floating rate is designed to keep it priced at $100. The way it will do this is: - MicroStrategy will just set the rate each month to whatever it thinks will get it to $100, but if it's wrong no biggie. This solves the first problem: There is no complex and gameable mechanism to set the interest rate; MicroStrategy just picks the rate that it thinks is best.

- If that process produces a rate that would be unpleasantly high for MicroStrategy, MicroStrategy will just pick a lower rate. If the rate required to make the thing trade at $100 would be, like, 20%, MicroStrategy has the flexibility to say "no thank you we'll stick to 9%."

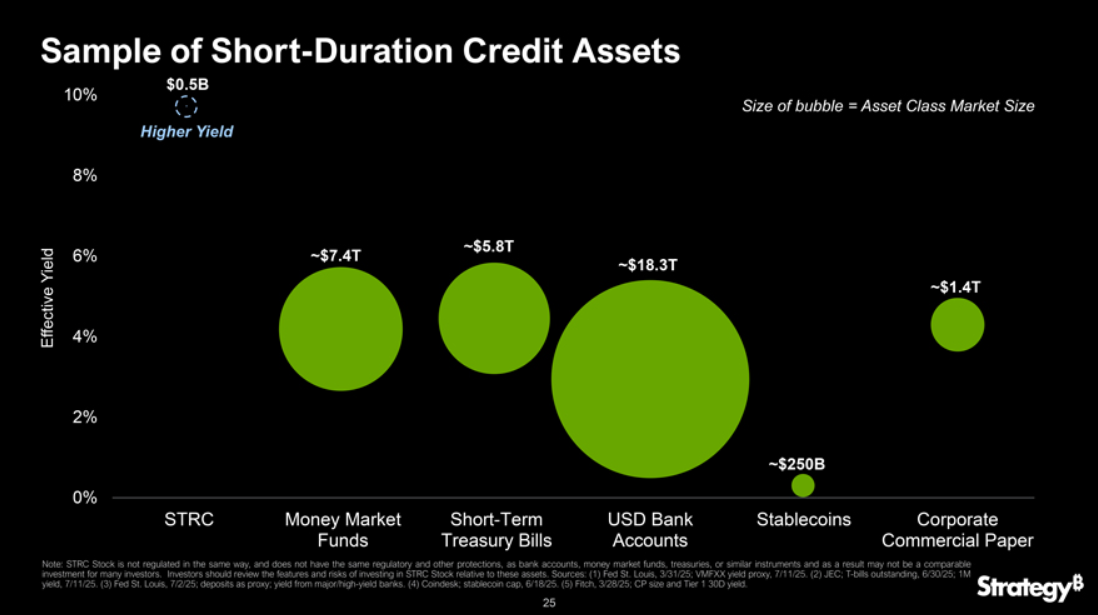

That is oversimplified but not by much. [2] From the prospectus: The initial regular dividend rate will be 9.00% per annum. However, we will have the right, in our sole and absolute discretion, to adjust the regular dividend rate applicable to subsequent regular dividend periods in the manner described in this prospectus supplement. ... Our current intention, which is subject to change in our sole and absolute discretion, is to adjust the regular dividend rate in such a manner as we believe will maintain STRC Stock's trading price at or close to its stated amount of $100 per share. For example, if the trading price of STRC Stock exceeds $100, our current intention would be to reduce the regular dividend rate with the goal of causing the trading price of STRC Stock to decrease. Similarly, if the trading price of STRC Stock is less than $100, our current intention would be to increase the regular dividend rate with the goal of causing the trading price of STRC Stock to appreciate. We will take any such actions at our sole discretion based on our subjective assessment of market conditions and the measures we believe are necessary to achieve our intended objectives. Here is the investor presentation, with slides with titles like "Building out the Yield Curve for BTC Credit" and "STRC is Designed to be Stable in Price." Because Stretch is a perpetual preferred stock, it is in some ways very long-term (perpetual) debt, but because its rate floats every month based on market conditions, it is in some ways like very short-term (monthly) debt. The presentation compares it to other short-term debt instruments:  Source: Strategy. I suppose the point here is that, compared to, you know, bank accounts, or Treasury bills, Stretch is much smaller, much higher-yielding and, though the presentation doesn't specifically say this, much weirder. This obviously demands a certain amount of trust, on the part of investors, in MicroStrategy. If you think "sure this thing won't trade above $100, because then they'd lower the rate, but if it trades below $100 they might be slower to raise the rate," then you might not want to pay $100 for it. (If it can only go down?) But on the other hand, everything in capital markets demands a certain amount of trust, and everything MicroStrategy does demands a bit more, and MicroStrategy does have a lot of fans. And because it is essentially in the business of finding weird new sources of capital, it does have incentives to be trustworthy: If this thing trades consistently at $100, people will want to buy whatever it cooks up next; if it doesn't, they won't. (The presentation also has a slide titled "Our Preferreds have Outperformed since their IPOs," which is why Strategy can sell new, weirder preferreds.) Strategy and its investors are all in this together: The more money Strategy makes for investors in its weird securities, the more weird securities it can issue to buy Bitcoin, and that is the business it is in. What? Elon Musk suggested any potential investment by Tesla Inc. in his artificial intelligence startup, xAI, should be proposed by the electric carmaker's shareholders. "Shareholders are welcome to put forward any shareholder proposals that they'd like," Musk said on Tesla's earnings call Wednesday in response to a question about a potential xAI investment. Musk offered support for such an investment from his X account earlier this month, but suggested that it wasn't his decision. That's not how any of this works. We talked last week about how (1) xAI needs a ton of money, (2) various other bits of Musk's empire (Tesla, SpaceX) have tons of money, (3) so, you know. SpaceX has agreed to send some of its money over to xAI, while Musk said, on X, "if it was up to me, Tesla would have invested in xAI long ago" and suggested that there might be a Tesla shareholder vote on doing so. Like an idiot, I took this hypothetical seriously and wrote about what sorts of formalities might be required for Tesla, a public company, to invest its money in one of its chief executive officer's other projects. (Ideally: A special committee of independent directors would negotiate the investment and then shareholders would vote.) I also wrote: Of course if you own Tesla stock it's not because of cars. … It's because you think that Musk is a really good allocator of capital to futuristic endeavors, and Tesla is his only public company, which just happens to be a car company. If Tesla was "an index fund for Musk's futuristic endeavors," you'd probably be fine with that.

That is: People own Tesla stock because they want Elon Musk to allocate capital for them. They don't want to do the capital allocation! They don't want to submit shareholder proposals telling him what to do! "Shareholders are welcome to put forward any shareholder proposals that they'd like"? Come on! Imagine what Musk would say if shareholders actually submitted proposals for what he should do. (Wouldn't the proposals be, like, "Resolved, shareholders would like Elon to spend less time on politics and getting in fights online"?) Shareholders of Elon Musk companies are not in the business of telling Elon Musk what to do with their money. They're in the business of letting Musk cook with their money. Also, even apart from the specifics of Elon Musk fandom, this is not how companies are run? A company's strategy is set by its executives and board of directors, not by shareholder proposals; shareholder proposals are normally nonbinding and cannot "micromanage" the company's decisions. If Tesla is going to invest in xAI, ideally shareholders would get a say — they'd get to vote on the idea — but the proposal would come from Musk, not from the shareholders. The way for shareholders to vote on it is for Musk to ask them to vote on it, not for them to ask him. I don't really know what's going on here. But one possibility is that, while Musk does want to pump more money into xAI, and while he does want Tesla shareholders to feel like they are participants in the broader futuristic Musk ecosystem, he doesn't actually want the constraints that would come from pumping public-company money into xAI. If he proposed it, Tesla probably would want a shareholder vote on it, which might mean public disclosure about xAI's finances and business plans, and which could mean shareholder lawsuits about disclosure and conflicts of interest and the fairness of the deal. (Though the lawsuits would be in Texas and Tesla would probably win.) It is useful for Musk's empire to have a big source of public money, but it is also useful for Musk to shield most of that empire from the public markets. Here's an insider trading hypothetical: - You are a financial professional, a research analyst or a small hedge fund manager, something like that.

- You get market-moving inside information about a company, in a bad way. Your brother-in-law is an executive at the company and he tells you that it's about to be acquired at a premium, that sort of thing.

- If you bought the company's stock or call options, you'd make a lot of money but you'd also obviously go to prison for insider trading.

- Several big multistrategy hedge funds run "alpha capture" programs. Basically there's a website where people — sell-side analysts, managers of smaller funds, etc. — can submit trade ideas, and the big hedge fund might use those ideas in its own trading. People who submit good ideas are rewarded, sometimes even if the big fund doesn't trade on them. For the big hedge fund, the point here is not so much "we give people a cut of the trades they bring us" and more "we want people to bring us good ideas, so we pay for good ideas whether or not we trade on them, because in the long term that gets us more good ideas." It also gives the big fund more data to evaluate which ideas are good. We talked last month about Marshall Wace's alpha capture program, which treats contributors' trade ideas as raw inputs to its own quantitative process for finding trades: "'It would be quite wrong to think of it as a simple translation of Joe Schmo's idea into a portfolio,' said Marshall. 'Joe Schmo may have an idea, and that might be a small part of a signal of whether or not that stock is interesting.'"

- You go to the website and put in "buy short-dated out-of-the-money call options on this company."

- The company announces its deal, the stock shoots up, and your trade turned out to be a good one. The big hedge fund writes you a check for your good trade.

- Did the big hedge fund use your idea? Did it literally do your suggested trade? Did it use your suggestion as an input to a model that slightly increased its long position in the company? You don't care.

You have turned your inside information into money. Do you also go to prison? A few arguments you might make here: - You never did a trade, so you didn't do insider trading. [3]

- The big hedge fund might not have done a trade, in which case it didn't do insider trading.

- Or maybe it did do a trade, but your submission was only one part of its quantitative process to evaluate what stocks to buy, so who can say whether it did insider trading. [4]

- Or maybe it did do a trade based entirely on your submission, but it didn't know that you had inside information, so it isn't guilty of insider trading. And if there was no insider trading by anyone, then you aren't guilty of insider trading.

I don't think those arguments are really right — not legal advice! — but they're tempting. And this is sort of a known problem, so the big funds that do alpha capture try quite hard not to get tips based on inside information, and to document that all of their information is legitimate. Still. One theory is that there is some incentive and opportunity to structure big hedge funds in a way that allows them to (1) trade on inside information but (2) insulate their executives from that information, so that the executives can say "how was I to know that we had inside information?" Letting unsupervised outside randos submit trade recommendations, and using those recommendations indirectly as signals in a quantitative process, might be one way to do that. Anyway Bloomberg's Lucca De Paoli reported yesterday: Squarepoint Capital collects ideas for its quant hedge fund from all over the world, with gleaming offices in London, Singapore, Dubai, New York and one above a Paris art gallery near the Champs Elysees. It also paid for stock tips from an Albanian day trader working in a cramped flat on the other side of London that she shared with her brother. Oerta Korfuzi toiled there on a large curved screen in the corner of her living room, squeezed between an alcove and a grey L-shaped sofa. That was until March 24, 2021, when agents from the Financial Conduct Authority arrested Oerta and her brother, Redinel, in a dawn raid. The siblings were convicted of insider trading and money laundering; Redinel, 38, was sentenced to six years in prison this month and Oerta, 36, got five years. Squarepoint, one of the world's best-known systematic investment funds, wasn't accused of any wrongdoing, and the Korfuzis' contributions to Squarepoint weren't what landed them in jail. It's not clear whether any of the tips they gave to the fund were based on insider information, or that Squarepoint acted on them. But the episode raises questions about what goes into the black-box process that some of the biggest quant hedge funds use to solicit ideas and help them invest billions of dollars. The Alpha Capture System, as it's known, seeks "signals" based on vast amounts of data and ideas pitched by thousands of outsiders in exchange for money. A computer-driven algorithmic model converts it all into lucrative trades. There's nothing illegal about it — investment firms have used such systems for decades. The hazard, as the Korfuzi trial showed, is that paying rewards might attract people with information they're not supposed to share, and whose methods and side hustles aren't always clear. The Korfuzis, for instance, were proffering trading ideas while also stuffing ill-gotten cash from other ventures that didn't involve Squarepoint into designer bags and transferring money to mysterious recipients in Albania. At some level "day-traders stuffing ill-gotten cash into designer bags" really is a differentiated source of alpha: If you have an alpha capture system, your goal is not to just get the same ideas that every other hedge fund analyst has; you want insights from people other funds don't talk to. At another level it does seem to raise compliance risks. Remember James Fishback, the guy who claimed to be the former "head of macro" at Greenlight Capital Inc., and who got a certain amount of public attention by relentlessly trolling Greenlight about it? He later expanded into anti-woke exchange-traded funds, and is generally a model for how to build a financial career through trolling. Anyway now he's suing the Federal Reserve for not being transparent enough. This stuff does seem to work for him. Sure why not whatever: GameSquare Holdings, Inc. (Nasdaq: GAME) (the "Company" or "GameSquare"), a next-generation media, entertainment, and technology company, today announced that its Board of Directors has approved the strategic purchase of a rare and highly sought-after "Cowboy Ape" CryptoPunk NFT from Robert Leshner, founder of the DeFi protocol Compound and CEO of Superstate. Under the terms of the purchase agreement, GameSquare issued Robert Leshner $5.15 million of preferred stock that is convertible into approximately 3.4 million shares of GameSquare's common stock at $1.50 per share. The purchase marks GameSquare's first direct NFT investment and is a major milestone in its blockchain-native brand and treasury strategy that is targeting 6-10% annualized stablecoin returns.

It will be amazing if all of the CryptoPunks and Bored Apes end up in the hands of crypto treasury companies. "The stock market will pay $2 for $1 worth of crypto," I keep saying, and maybe it's the last bid for nonfungible tokens too. 'A long, slow bleed': Quant hedge funds are getting slammed and scrambling for answers. Hayes Calls for All Rate-Rigging Convictions to Be Overturned. Morgan Stanley's Screening of Wealth-Management Clients Draws More Scrutiny. BlackRock Private Funds Face Attempted Exit by Key Investor Arch. Carlyle to Buy $250 Million of Farm Loans in Private Credit Deal. Goldman and BNY Team Up to Tokenize Money-Market Funds. A Billionaire's Quest to Find Credit Suisse Nazi Accounts Puts UBS in the Spotlight. Goldman Sachs to forgo second round of job cuts as outlook improves. PredictIt Says It Can Expand Political Trades With CFTC Deal. Replit's AI Agent Wipes Company's Codebase During Vibecoding Session. Lamb Weston Plans More Restructuring as French Fry Demand Faces Tough Environment. Sydney Sweeney sparks latest meme stock rally as American Eagle soars 12%. You Can Now Venmo the Government to Help Pay Off National Debt. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! |

No comments