It’s ugly out there — but don’t hit the panic button yet

Last week, the Fed didn't cut rates like everyone was hoping. Then US jobs data

came in shockingly low. The Bank of Japan raised rates at the worst possible

time, leaving the yen-carry trade camp scrambling. Over the weekend, Warren

Buffett added to the chaos when he announced he sold half his Apple stock and

now has a huge pile of cash. Today, the S&P 500 had the biggest one-day drop

since September 2022 and everyone with a 401(k) is freaking out. Traders want

the Fed to do an emergency rate cut to calm things down.

As you can see, there isn't One Big Thing we can blame the market rout on. On one hand, that's good, because it means there's no catastrophic emergency that's railing the economy à la Covid-19. But on the other hand, the lack of a clear culprit makes this sequence of events rather messy and confusing. In an attempt to remedy that, here's a more in-depth recap from our columnists.

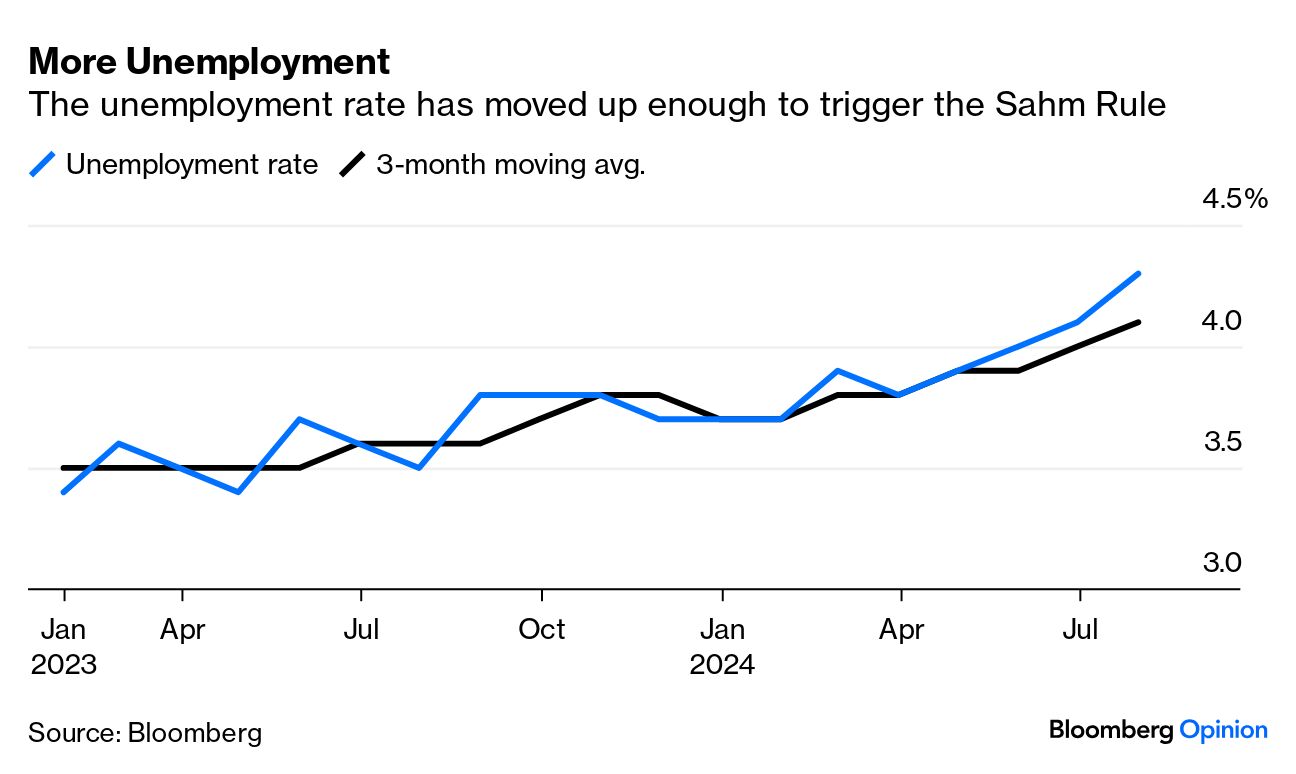

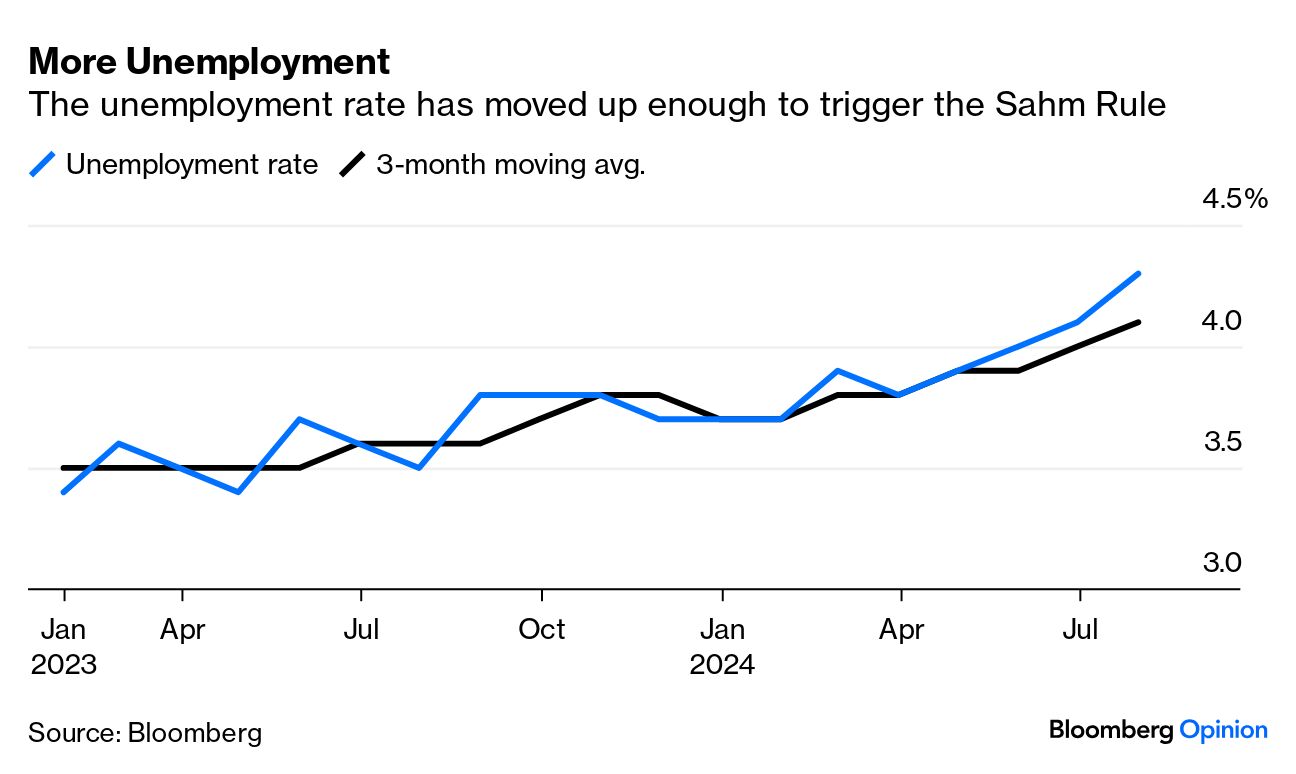

When the US unemployment rate surged to the highest level in nearly three years on Friday — exceeding all 69 estimates from economists surveyed by Bloomberg — it triggered Claudia Sahm's namesake indicator, which says the economy is already in a recession once the three-month average of the unemployment rate rises at least a half percentage point above its low in the past 12 months:

"If the market expectations of a US recession turn out to be true," Gearoid Reidy says the Bank of Japan's move "will prove to once again have been spectacularly poorly timed." The bank's July 31 rate hike decision "has been followed by a market bloodbath of almost unprecedented levels," he writes, but it appears to be more of an unfortunate coincidence than malpractice.

What's the connective tissue between Japan and the US? John Authers explains: "Japanese investors love putting their money to work overseas. Combine the extraordinary performance of the US stock market with a historically weakening yen, and the result for Japanese investors is fantastic," he writes. "Meanwhile, foreign investors also like borrowing in yen and parking elsewhere via the carry trade. Like Mrs. Watanabe, the mythical Japanese retail investor, these people will be burned, and their actions as they try to minimize the pain could make the situation worse. By liquidating their foreign holdings and bringing money home, they drive the yen up further."

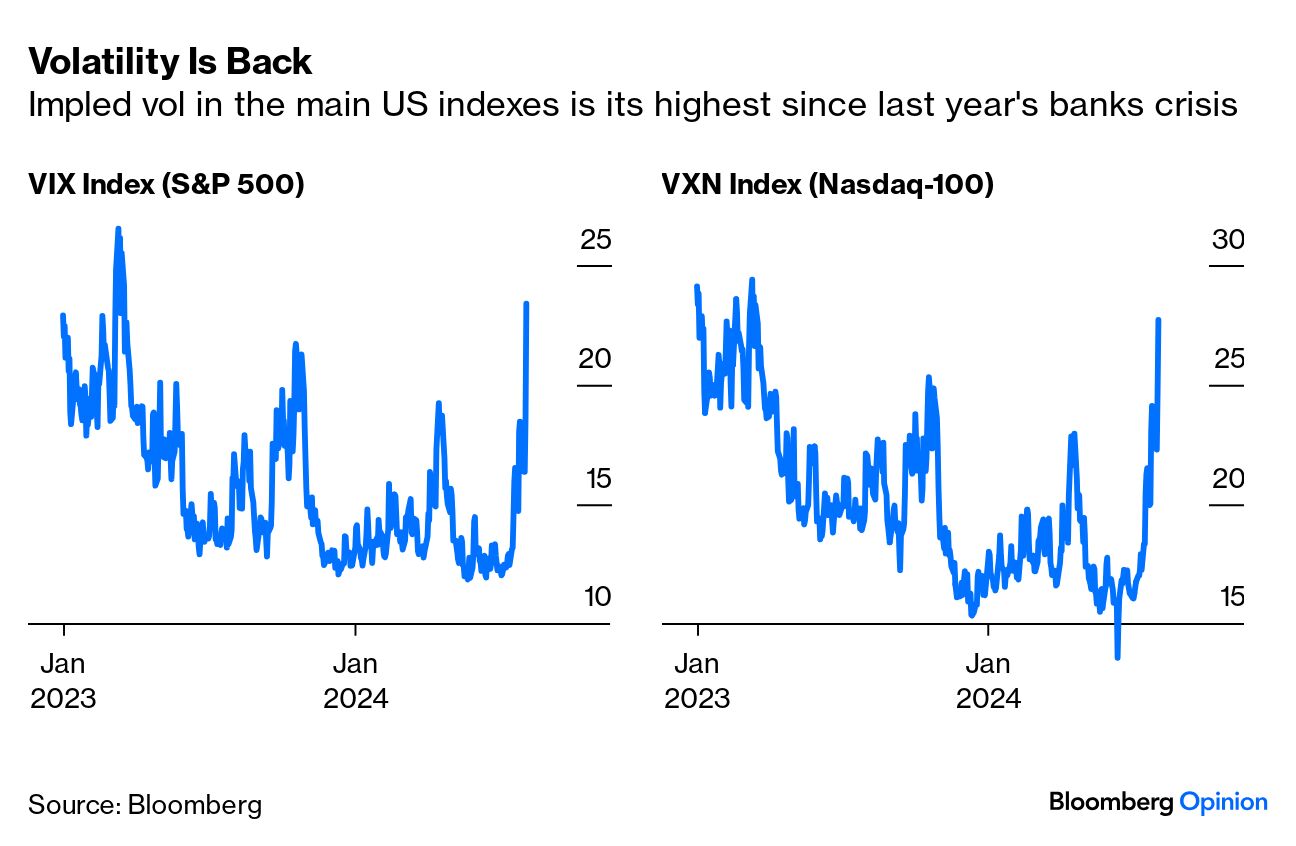

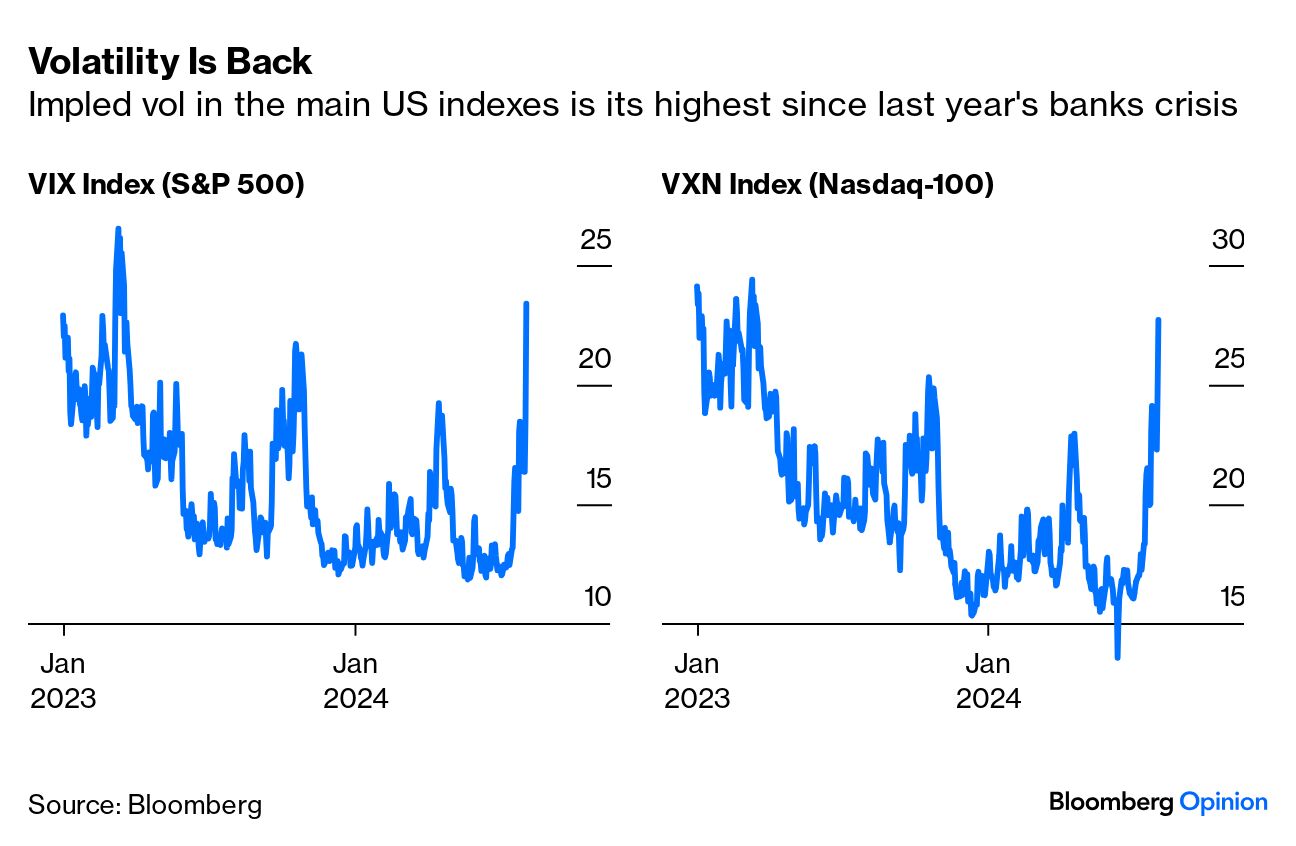

Wall Street's so-called "fear gauge" — the volatility index — is through the roof. And bright minds are cooking up nightmare nicknames for the event: "Volmageddon is kinda lame. We need something for the ninja element," Steve Hou tweeted. Kyla Scanlon offered "Yenvolcalypse," which feels appropriate:

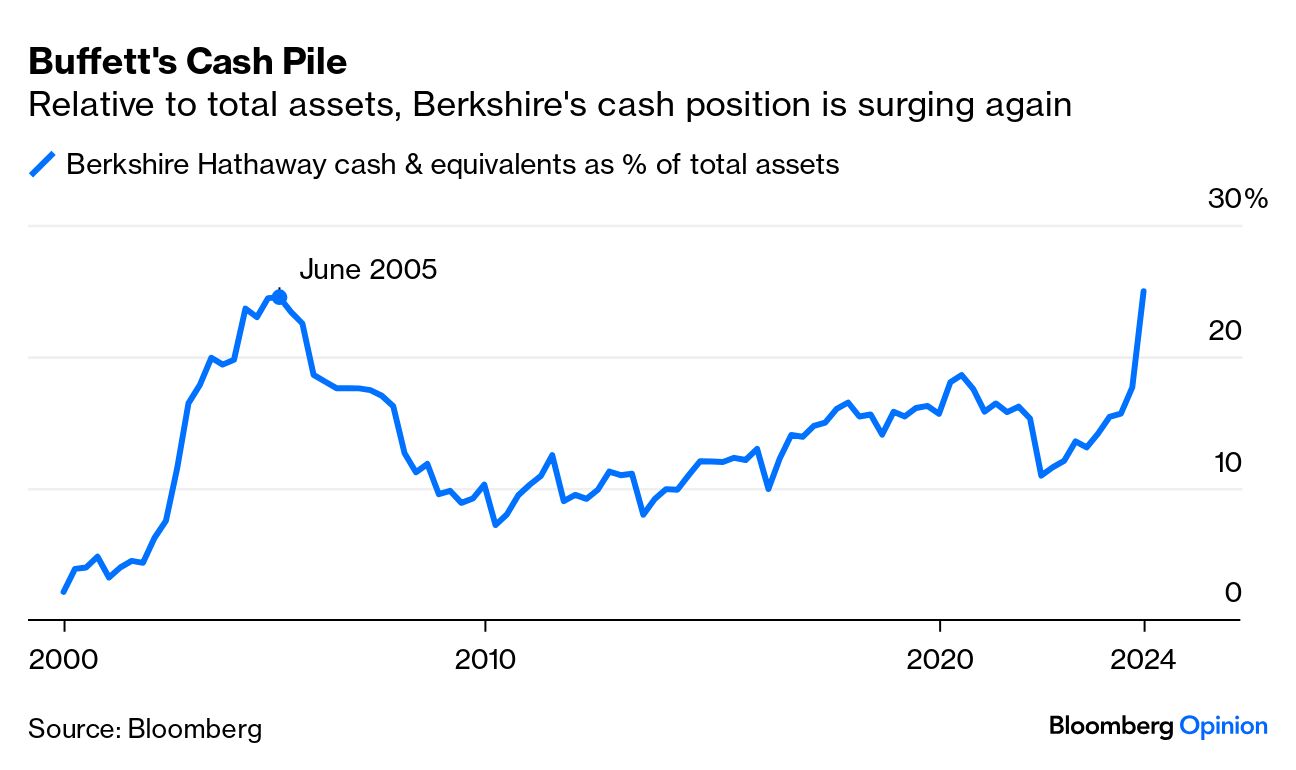

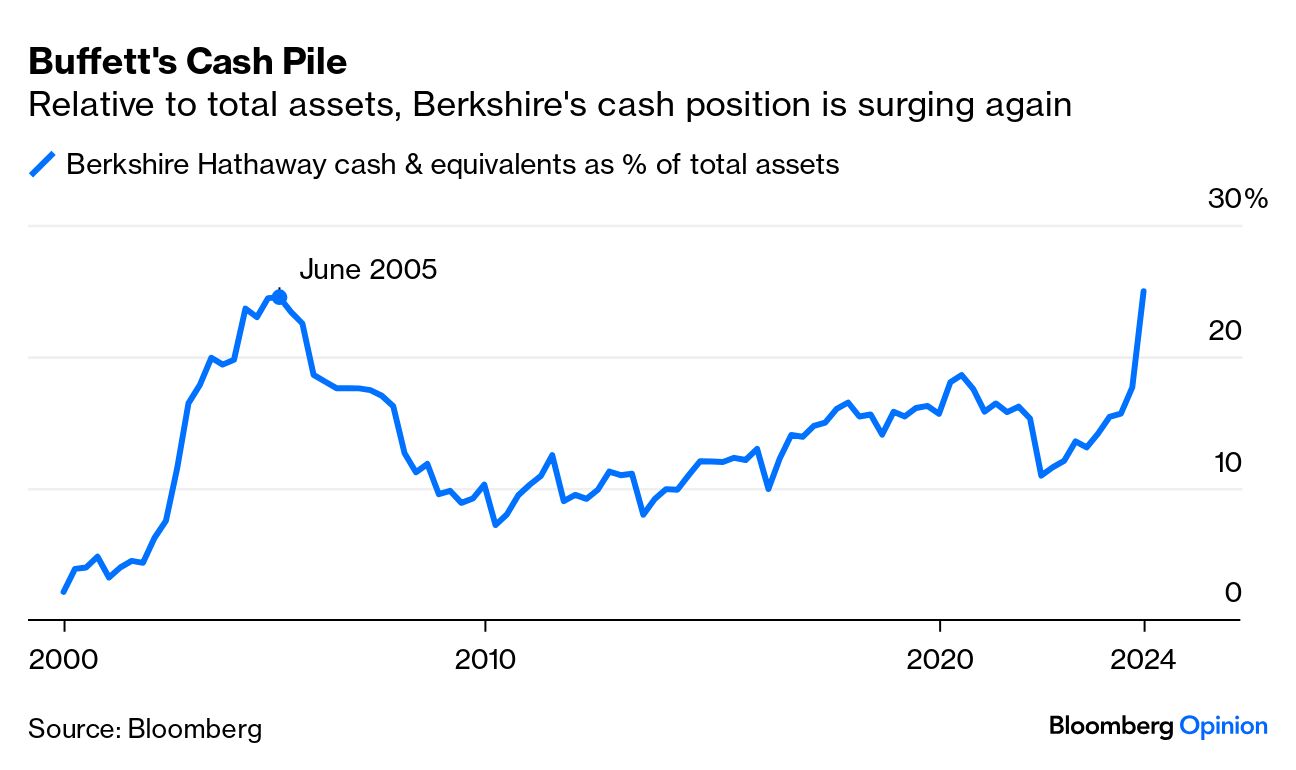

Over the weekend, Warren Buffett added fuel to the fire when he announced Berkshire Hathaway slashed its stake in Apple. As John puts it: "The sight of the world's most respected investor getting out of one of the Magnificent Seven and building a $276.9 billion cash pile for the buying opportunities he sees ahead is not good for rattled sentiment." Jonathan Levin agrees: "At [noon in New York], the S&P 500 Index had plummeted around 3%. I have no idea what proportion of that reflects Buffett, but it's fair to say that his unfortunately timed disclosure was part of the ssentiment stew."

"If we really are heading into recession, there's not much disagreement on what the Fed should do: Cut interest rates a lot and fast," Conor Sen writes. "Swift rate cuts would relieve pressure for Americans struggling to make payments on floating-rate credit card debt or to get financing for a new car." Some folks including Wharton School Professor Jeremy Siegel want the Fed to do a 75 basis-point emergency cut to its funds rate now. But Marcus Ashworth says that's "highly unlikely," considering what we've seen in the past. "Emergency rate cuts do happen," he writes, "but they're relatively rare, and are only employed when the economy is facing a sudden seizure." Think: March 2020, the global financial crisis and the 2001 tech bubble burst.

As you can see, there isn't One Big Thing we can blame the market rout on. On one hand, that's good, because it means there's no catastrophic emergency that's railing the economy à la Covid-19. But on the other hand, the lack of a clear culprit makes this sequence of events rather messy and confusing. In an attempt to remedy that, here's a more in-depth recap from our columnists.

When the US unemployment rate surged to the highest level in nearly three years on Friday — exceeding all 69 estimates from economists surveyed by Bloomberg — it triggered Claudia Sahm's namesake indicator, which says the economy is already in a recession once the three-month average of the unemployment rate rises at least a half percentage point above its low in the past 12 months:

"If the market expectations of a US recession turn out to be true," Gearoid Reidy says the Bank of Japan's move "will prove to once again have been spectacularly poorly timed." The bank's July 31 rate hike decision "has been followed by a market bloodbath of almost unprecedented levels," he writes, but it appears to be more of an unfortunate coincidence than malpractice.

What's the connective tissue between Japan and the US? John Authers explains: "Japanese investors love putting their money to work overseas. Combine the extraordinary performance of the US stock market with a historically weakening yen, and the result for Japanese investors is fantastic," he writes. "Meanwhile, foreign investors also like borrowing in yen and parking elsewhere via the carry trade. Like Mrs. Watanabe, the mythical Japanese retail investor, these people will be burned, and their actions as they try to minimize the pain could make the situation worse. By liquidating their foreign holdings and bringing money home, they drive the yen up further."

Wall Street's so-called "fear gauge" — the volatility index — is through the roof. And bright minds are cooking up nightmare nicknames for the event: "Volmageddon is kinda lame. We need something for the ninja element," Steve Hou tweeted. Kyla Scanlon offered "Yenvolcalypse," which feels appropriate:

Over the weekend, Warren Buffett added fuel to the fire when he announced Berkshire Hathaway slashed its stake in Apple. As John puts it: "The sight of the world's most respected investor getting out of one of the Magnificent Seven and building a $276.9 billion cash pile for the buying opportunities he sees ahead is not good for rattled sentiment." Jonathan Levin agrees: "At [noon in New York], the S&P 500 Index had plummeted around 3%. I have no idea what proportion of that reflects Buffett, but it's fair to say that his unfortunately timed disclosure was part of the ssentiment stew."

"If we really are heading into recession, there's not much disagreement on what the Fed should do: Cut interest rates a lot and fast," Conor Sen writes. "Swift rate cuts would relieve pressure for Americans struggling to make payments on floating-rate credit card debt or to get financing for a new car." Some folks including Wharton School Professor Jeremy Siegel want the Fed to do a 75 basis-point emergency cut to its funds rate now. But Marcus Ashworth says that's "highly unlikely," considering what we've seen in the past. "Emergency rate cuts do happen," he writes, "but they're relatively rare, and are only employed when the economy is facing a sudden seizure." Think: March 2020, the global financial crisis and the 2001 tech bubble burst.

No comments